Words as Politics at Gettysburg

by Rob Zaretsky

Today, words as politics at Gettysburg. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

This episode will last about three minutes. This seems like a lot of time in an age of sound bites. And it seems like no time at all in an age of perpetual media. Either way, it seems like too much, or too little time to say something important about our world, much less change it.

But in slightly more than twenty-five score seconds, Abraham Lincoln did both. As the historian Garry Wills writes, the "power of words has rarely been given a more compelling demonstration" than at Gettysburg in 1863.

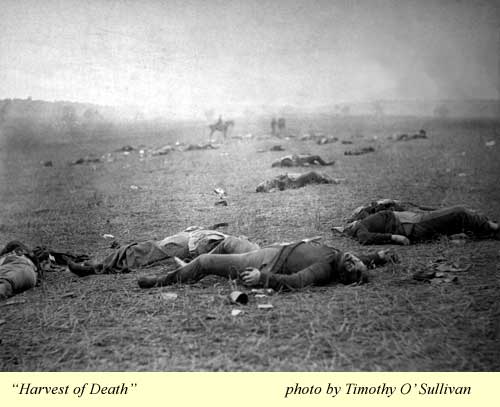

The battle of Gettysburg ended with more than 50,000 casualties on both sides. The chaos and carnage of the battlefield were turned into a proper cemetery, dedicated on November 18 of that year. President Lincoln attended the ceremony, but the top-billed speaker was the scholar Edward Everett. Everett spoke well, he spoke learnedly and he spoke long. Very long. This was fine with the crowd of 20,000: they warmly applauded Everett's two-hour speech.

Lincoln next stepped to the podium. In his hand he held two sheets of paper. In a high-pitched tenor, he read from his text. Scarcely three minutes after he had stood up, he again sat down. These three minutes, though, reinvented the United States.

The reinvention begins with the phrase "four score and seven years ago." The biblical cadence suggests divine justification for the North's cause. But it also makes us pause. When did you last subtract four score and seven -- in other words, 87 -- from 1863? Do the math: you're left with 1776. Now, wait a second: didn't the Founding Fathers create the Constitution, the nation's legal document, in 1787 -- three score and sixteen years before?

But Lincoln's math was good; his language, couching his moral vision, even better. Speaking in a place where coffins were still piled high, a place where he himself was still wearing a mourning band for his dead son, Lincoln had some explaining to do. Where better to start, and end, than the Declaration of Independence?

Taking his cue from classical Greek texts, Lincoln uses a series of antitheses: for example, "The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here." Rarely have so few words said so much about so great a cause.

Lincoln also reminds his audience that this nation is "dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal." Yet the Constitution declared slaves were less equal than others. For many of Lincoln's contemporaries, the Constitution, not the Declaration, made our nation. Lincoln reverses the order.

Lincoln's more perceptive contemporaries saw his sleight-of-hand. And all recognized what it meant. Just as they all understood that, in politics, mere words are, at times, neither "mere" nor "words."

I'm Rob Zaretsky at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

G. Wills, Lincoln at Gettysburg: The Words that Remade America. (New York: Simon & Schuster 1993).