The Lunar Society

Today, let's drop in on a remarkable gathering. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

It was called The Lunar Society of Birmingham, and it was active for at least sixteen years, beginning in 1775. It got its name from the practice of meeting each month on the Monday nearest to the full moon. That way, roads were better lit for members who had to travel at night.

Revolutionaries have always gathered in small groups, and this was a revolutionary group. The revolutions of the late eighteenth century took many forms, but they were all fomented in study groups. And these groups invariably got around to a common question: How could science and technology be made to serve society?

Ben Franklin had helped to set the pattern very early in the game. His life was centered both on revolution and on tying scientific knowledge to practical social change. And The American Philosophical Society started out as his study group.

Before the French Revolution, intellectuals (both men and women) gathered in salons to talk about scientific and social issues. Now the English Industrial Revolution was about to become the ultimate fusion of science, social change, and revolution. And the Lunar Society formed a primary focus for such change.

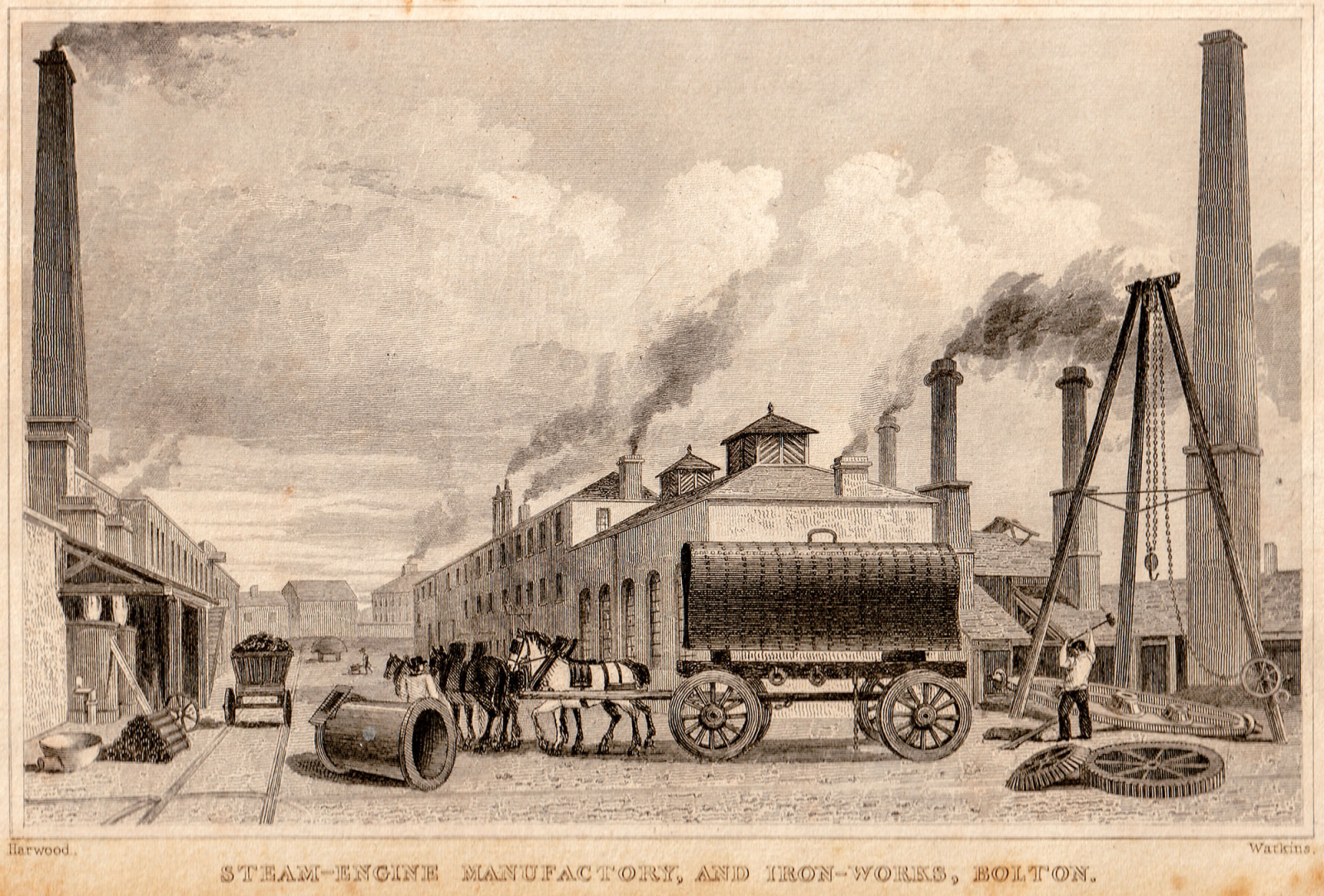

But, if the Lunar Society was not unique for its aims, it was certainly unique for its membership. It numbered only a dozen or so people, but what a dozen they were! The heart of the Society was Matthew Boulton, the industrialist who built Watt's engines.

Other members included James Watt, Erasmus Darwin (famous physician and writer and Charles Darwin's grandfather), and Joseph Priestley. Priestley was the rebellious cleric and scientist, famous for isolating oxygen. Josiah Wedgwood was known for fine tableware, but he was also dedicated to improving everyday life. He made huge contributions to the production of cheap tableware. (And Wedgwood was Charles Darwin's other grandfather.)

The roster goes on: the astronomer William Herschel, who discovered the planet Uranus was also a famous organist in his day. John Smeaton, designer of the Eddystone lighthouse, knew more about steam-engine design than anyone before Watt.

Can you imagine being in a room with these makers of the Industrial Revolution who were genuinely asking how to improve their world? Historian Jacob Bronowski looks at the Lunar Society and says,

What ran through it was a simple faith: the good life is more than material decency, but the good life must be based on material decency.

It comes as a jolt to see these dedicated capitalists as part of a revolutionary cabal. But capitalism was revolution in the late eighteenth century. When this group of writers, intellectuals, scientists, and industrialists consciously joined forces, it was precisely because they meant to shape a decent life for everyone.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Bronowski, J., The Ascent of Man. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1973, Chapter 8, The Drive for Power.

Schofield, R. E., The Lunar Society at Birmingham: A social history of provincial science and industry in eighteenth-century England, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1963.

This is a greatly revised version of Episode 168.

Boulton-Watt Works in Birmingham, England as shown in a 19th-Century Engraving, Source Unknown