Temple Grandin

by Andrew Boyd

Today, the unspeakable. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

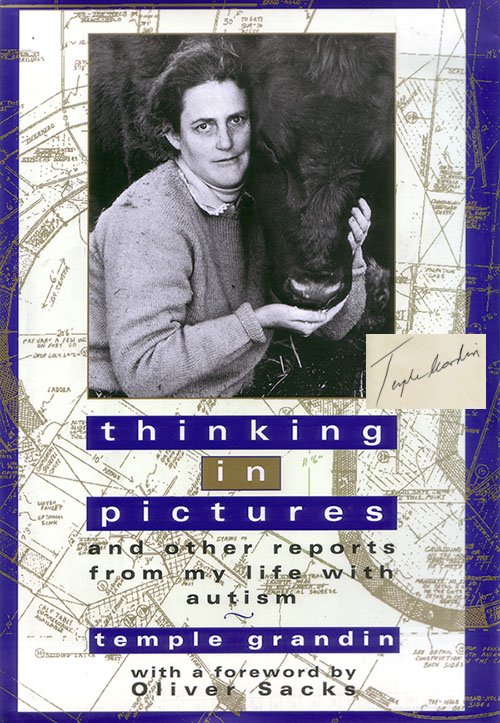

A book cover shows a woman peacefully cradling the head of a cow in her arms. She is Dr. Temple Grandin, and over a third of the cattle and hogs in the United States are handled in facilities that she has designed. Her life's calling is the humane treatment of livestock up to the moment they're slaughtered. What makes her story especially compelling is that she is autistic.

Meat packing facilities need to keep animals moving. When animals refuse, work stops. To keep them moving, facility workers use cattle prods. Cattle prods can be very painful, especially those that operate like police stun guns. When prodding doesn't do the job, workers become frustrated and unspeakable abuse may occur.

For Grandin, the perfect meat packing facility would keep livestock peaceful from plant arrival to slaughter. Her designs are devised to calm the animals and keep the system moving. She achieves this by taking "a cow's eye view."

Animals stop moving or become unruly when they're afraid. But according to Grandin, the things that frighten cattle usually have nothing to do with death. Instead, it's little things that you and I might completely overlook. Grandin doesn't.

She recalls one case where a meat packing plant was thrown into chaos because a plastic juice bottle had fallen in the path of some animals. In another case, a loud, high pitched bell on a telephone was the culprit. Inadequate light is a frequent problem. Grandin draws parallels with autism.

Autistics are often highly sensitized to the world around them. Changes in light, sound, and routine may produce severe anxiety. Unwanted touch can be agonizing. Grandin believes that her autism puts her in a better position to understand animals, even as it limits her ability to form emotional attachment to those same animals.

One of the most stressful events faced by many cattle is the presence of people. A person leaning over a passageway is very threatening. Grandin advocates solid walls so that cattle are visually protected. Her passageway designs incorporate curves so that cattle can't see people at the end. The curves also play into the soothing, natural tendency of cattle to circle.

Grandin understands discomfort with people. Autistics are often good with structured activities, like spelling words or doing arithmetic. But people are enigmatic to the autistic since they can't be described by a set of rules. To Grandin's credit, she has learned that not everything is an equation. In her own words, "Good engineering is important, and well-designed facilities make low stress, quiet handling at slaughter possible, but employees must operate the system correctly. Rough, callous people will cause distress to animals even if they use the best equipment possible."

Measured by her actions, Grandin is a compassionate woman. She eases animal suffering. Yet her autism leaves her to deal with animals dispassionately. And this allows her to address engineering problems that must solved, but that most animal lovers couldn't face. Maybe this is the greatest form of compassion.

I'm Andy Boyd, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

T. Grandin, Thinking in Pictures and Other reports from My Life With Autism.(New York: Doubleday, 1995).

See/hear also this powerful NPR essay by Grandin (accessed Feb. 13, 2008).