Iceboats on the Hudson

Today, we go iceboating. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

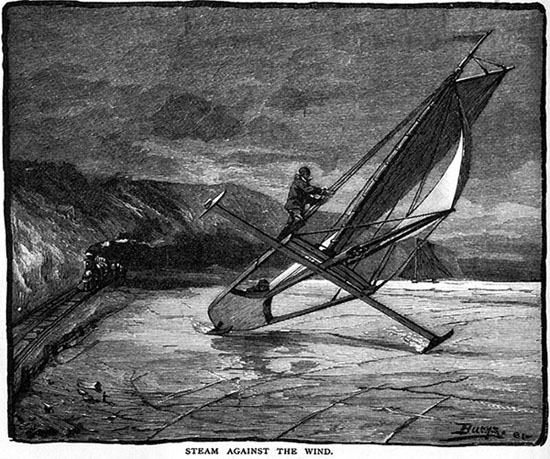

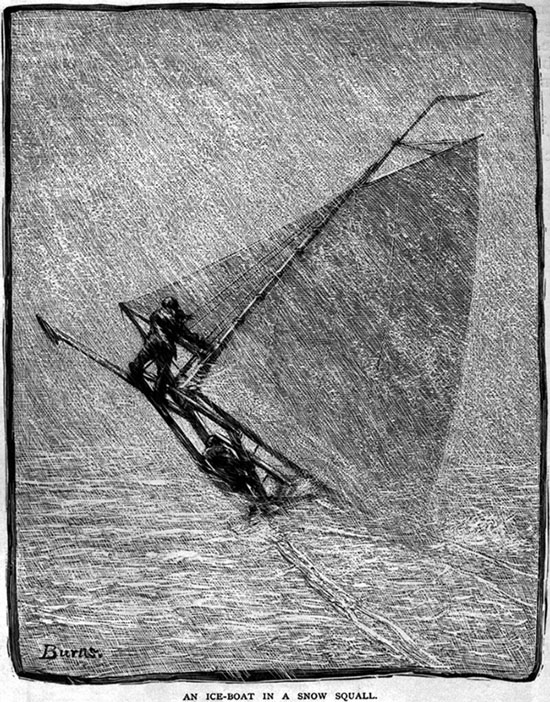

The sport of iceboating is alien to our warm Texas coast. So the raw intensity of an 1881 Scribner's article, Ice-Yachting on the Hudson, takes me by surprise. Its engravings could pass as concept sketches for a special effects action movie.

Iceboats are lean and spare. A vertical sail rises from a horizontal cross-shaped frame running on three skates. A rudder handle turns the rear skate for steering. Iceboats are well-known in Northern European history. And, until the 20th century, they'd carried humans the fastest they'd ever gone. So this article becomes raw theatre. Iceboats, it says, reach 80 to a 100 miles an hour on clear stretches of smooth ice. It'd be another ten years before a locomotive passed 80 miles an hour -- another 30 before flying machines did so.

We might expect that gale-force winds were needed to get such speeds. They were not. Iceboats move far faster than the winds that propel them. They have a singular advantage over sailboats because they offer such low drag. A cross breeze exerts a modest pulling force on the sail while the boat's motion is nearly perpendicular to that breeze. Since the drag is so low, that small force can sustain a very high speed. A pure tail wind is actually a disadvantage. An iceboat has no way to travel faster than the wind if the wind is right at its back.

So, let's look at pictures: The curious stand about as yachtsmen assemble their boats. Skaters dart around a row of iceboats at a starting line. Riders of a horse-drawn sleigh wave as boats whip past them. Here are iceboats rearing off the ice -- standing on two, or even just one, of their skates. A man stands on an outrigger to keep from overturning while another struggles to steer. And, finally, a dray horse hauls a wrecked boat off the ice.

Like many sports, iceboats have adopted new materials and have taken on a modern look. But nothing as extreme as, say, modern archery with its unrecognizable bows. The official iceboat speed record remains the one set on Lake Winnebago, Wisconsin, way back in 1938. It was (hold your breath) 143 miles an hour.

The writer has just ridden an iceboat and here's his reaction: "You are not shut up in a ponderous train -- a whole world of material, roaring, jolting matter. Here you fly alone through the keen air and flashing sunshine, with the speed of a bird soaring in the sky."

But he realizes that flight, when we achieve it, won't be the same. "Your eyes," he says, "are not those of an eagle." Rather, as you fly inches above the ice, "objects seem melted down and drawn out into blurred, elongated forms." The force of gravity is destroyed and; our bodies seem to lose all material existence.

Now people see the iceboat against the backdrop of hang-gliding and sky-diving. The setting is changed. We need to imagine, say, world-class surf-boarding in a Courier and Ives print, to better understand the immensity of what we find in this old magazine.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

C. H. Farnham, Ice-Yachting on the Hudson. Scribner's Monthly, An Illustrated Magazine for the People, Vol. XII, May to October, 1881, pp. 528-539. (See also, C. H. Farnham, How to Build an Ice-Yacht. pp. 658-665, in the same issue of Scribner's.) All illustrations from these sources.

Click Here to see Farnham's design of an iceboat.

Click Here to see details of Farnham's design of the rudder and the attached skate.

Click Here to see other rigging details in Farnham's design.