ETAOIN and SHRDLU

Today, we learn about Etaoin Shrdlu. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Ogden Nash, beloved master of American doggerel, once wrote about a fellow at an eye exam.

And you look at his chart and it says SHRDLU QWERTYOP, and you say Well, why SHRDNTLU QWERTYOP? and he says one set of glasses won't do.

You need two.

Nash did not just pick the man's imagined letters at random. You might recognize QWERTYOP as the first six and last two letters on the top row of your computer keyboard. But what's SHRDLU?

The name Etaoin Shrdlu often turns up as a comic character's name. Qwertyop isn't used that way -- it's too familiar. But long ago I read about Etaoin Shrdlu in Max Schulman's comic novel Barefoot Boy With Cheek.Robert Crumb uses that name. An early artificial intelligence system was named SHRDLU. And so forth.

To see why Ogden Nash linked SHRDLU and QWERTYOP, consider: He was born in 1902 and died in '71. He was honored on a 2002 US stamp; but he wrote in an earlier era -- in the heyday of linotype-printing. The fiendishly complex Linotype type-setting machine was perfected during the 1880s -- same time as the typewriter. But those tools of every early 20th-century writer's life had evolved quite independently.

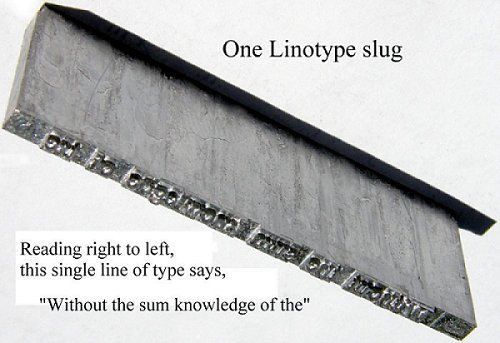

Linotype operators type out one-line slugs of finished type, and leave printing to be done separately. The typewriter prints one finished letter at a time on piece of paper.

Linotype operators call down individual letters from a magazine. They form a row of letters that then becomes a die. It's used to cast a one-line slug in a molten lead alloy. Since Linotype machines hold separate bins of capital and lower case letters; the keyboard has separate keys for caps and lower case. Linotype keyboards have nothing in common with typewriters.

When a Linotype operator makes an error, he needs to mark the bad slug clearly so the type assembler won't miss it. So he runs his right hand down two rows of keys. Those capital letters boldly spell the nonsense phrase ETAOIN SHRDLU on the bad slug.

Yesterday, I watched a Linotype operator using the Linotype in our Museum of Printing History. I saw there was still more to the keyboard: Since there's no shift key, all the special-symbol keys are in the middle, between the upper and lower case letters.

As his fingers flew across that crazy keyboard, I asked if he were bilingual -- did he also type on a QWERTY keyboard. Yes, he did. Then he handed me a set of slugs. No ETAOIN SHRDLUs but, on one, two letters were transposed. I didn't see it right away because there's another wrinkle. Like that assembler who checks the slugs, I had to read the text backward.

So, Nash's hapless eye patient looked at blurry fine print and saw the parallel evolution of two new technologies. SHRDLU QWERTYOP was Nash's code for the radical spread of the written word in his new century. (Well, as long at the print wasn't too small.)

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

More on ETAOIN SHRDLU, Ogden Nash, and Linotype machines at:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ETAOIN_SHRDLU

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ogden_Nash

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Linotype_machine

For more on the early Linotype competitor and early typewriters, see:

Episode 1372

Episode 1532

Below: Top, Linotype keyboard-- note the vertical ETAOIN and SHRDLU rows on the right. The second image is a Linotype slug. Third, Linotype machine. Bottom, 1898 Oliver #3 "Visible Typewriter" -- visible since you could see what you were typing -- with QWERTYOP row highlighted. (All photos taken by JHL at the Houston Museum of Printing History.)

I am grateful to linotype operator Dan Williams at the Houston Museum of Printing History for his demonstrations and his counsel.