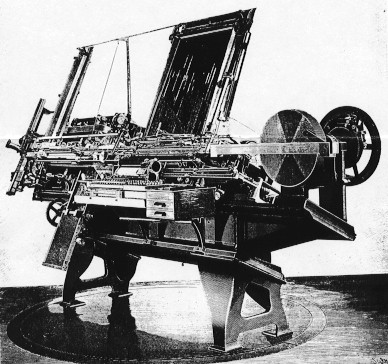

The Paige Compositor

Today, meet the man who bankrupted Mark Twain. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

From Gutenberg down through the 19th century, typesetters all had to pick up, then position, one letter at a time. It was slow, intense work. In the early 1800s it became clear that that would have to change. The new fast presses were driving the output of printed material skyward. In the 1820s inventors began looking for ways to mechanize typesetting. In 1884 Ottmar Mergenthaler finally emerged from a pack of competitors with his Linotype machine. Linotype operators set type five times faster than hand typesetters could.

Historian Judith Lee tells about Mergenthaler's most fascinating competitor. James Paige patented the Paige Compositor in 1872. Five years later he joined with the Farnham Company, and they turned to their best-known investor, Mark Twain, for support. Twain was intrigued by Paige's machine and began putting money into its development. By 1882 Paige had a functioning compositor.

On the surface, Paige was coming up roses, but he'd made two subtle mistakes in his design. The first was his compulsion to keep improving it. He wasn't ready with a production version until 1887. By then, Linotype machines had been on the market for three years. That didn't worry Paige. He was certain he had the better machine. His Compositor could set type sixty percent faster than the Linotype. How could he lose!

Mark Twain had long since become a true believer in Paige's Compositor. By now he'd assumed the major financial responsibility in exchange for a percentage of anticipated profits.

Then Paige's second mistake surfaced. The Compositor was a temperamental racehorse. The Linotype was a steady workhorse. Paige had designed his machine to function like a human being. He'd consciously copied human hand motions. Mergenthaler had made his Linotype without reference to human function. He understood that machines can move in ways that humans cannot. So his Linotype was simpler, cheaper, easier to maintain, and less liable to break down. Machine tolerances weren't as tight.

With 18,000 parts, Paige's Compositor was far more complicated. Of course it priced itself out of the market. It took until 1894 for the competitive failure of the Compositor to become complete. After that, Paige died penniless in a poorhouse and Mark Twain went bankrupt. Twain later observed that he'd learned two things from the experience -- not to invest when you can't afford to, and not to invest when you can.

The last surviving Compositor is housed in the Mark Twain Memorial in Hartford, Connecticut. It's a beautiful machine, but it reminds us that good designs have to do more than carry out a function. They have to be robust and uncomplicated. Good designs find that solid simplicity which is at the root of anything worthwhile.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Lee, J. Y., Anatomy of a Fascinating Failure, American Heritage of Invention and Technology, Summer 1987, pp. 55-60.

I found that a comparison of the 1897 and 1970 Encyclopaedia Britannicas was instructive here. The 1897 Britannica Supplement doesn't yet mention Mergenthaler. It gives pictures of three soon-to-be forgotten competitors. The 1970 Britannica account is dominated by Mergenthaler's Linotype and its subsequent evolution. Paige is not mentioned in either account. This is a reworked version of Episode 50.

The Paige Compositor

From Inland Printer, 1903

Mergenthaler's Linotype Machine

From Appleton's Cyclopaedia of Applied Mechanics, 1892

Image from Munsey's Magazine, April, 1897