Old Scientific Illustrations

Today, Aesop's fables illustrate a new science. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Francis Bacon spelled out the form of modern science in 1620. Those new means for using systematic observation to learn about nature had been evolving since Leonardo; but we now set out methodically to observe nature and thus expose a body of scientific law.

Yet, that process had far to go before it would look like our scientific method. Scientific paraphernalia was skimpy 400 years ago -- lacking our instruments, labs, and techniques for doing business. Think for example, about one piece of it -- scientific illustration. My whole life was spelled out in drafting, graph plotting, schematic diagrams. We created that language of exposition in the wake of Bacon. And now, the language's vocabulary is expanding once more -- faster than we can follow it.

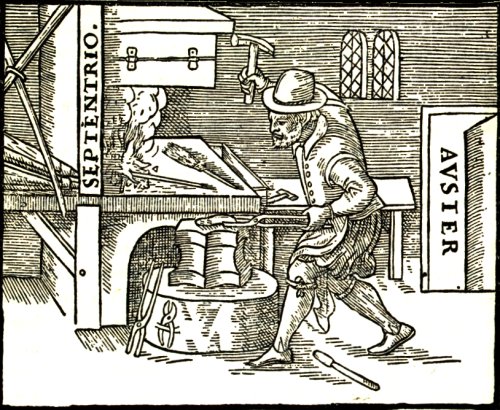

When William Gilbert wrote his remarkable book on magnetism in 1600, he had to feel his way. He told how to align a red-hot bar in a north/south direction, and induce magnetism by forging it.

Then Gilbert wanted a picture of a blacksmith to go with his text. So did he send an artist to a blacksmith's shop? No, nor did he copy one of the many blacksmiths pictured in Agricola's book on mining. Instead, Gilbert went to a popular book on Aesop's fables by Marcus Gheeraerts. He copied Gheeraerts's illustration for Aesop's fable about a blacksmith and his dog. Well, he did mirror-image it, erase the dog, and update the smith's clothing.

But it simply didn't occur to Gilbert to hunt down an accurate source. Gheeraerts's book of fables was widely read. When people saw a picture of a blacksmith, they expected it to look like Gheeraerts's smith, so that's what Gilbert gave them. And here the plot thickens, for during the next hundred years, so did every other scientific writer who needed to portray a smith.

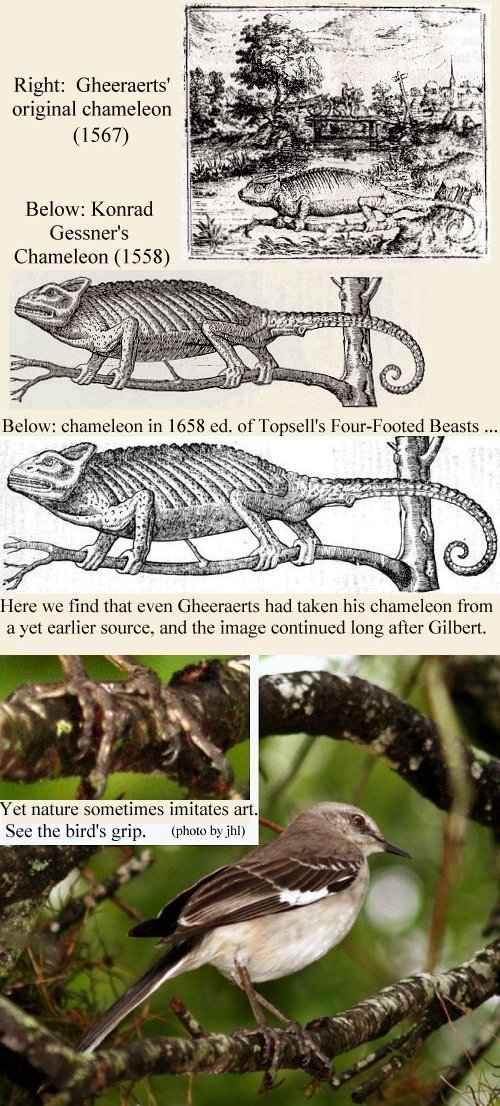

All that grows stranger still when we read old books on zoology. A zoologist showing a picture of a chameleon is presenting data. It really ought to look like a chameleon. But chameleons were important 16th-century symbols of duplicity -- so powerful as symbols that Gheeraerts had actually made up his own Aesop's fable about a chameleon, just so he could have one in his book.

His chameleon, clinging to a branch with four prehensile feet, was asymmetric; all four feet grasped the branch from the right-hand side. And for the next hundred years, every zoologist who drew a chameleon showed him on that same branch with the same crazy one-sided grip.

So the first order of business for the new science was to claw its way free of fables. It needed a new home -- free of the rich and fanciful conventions in which it was born. In the 18th century, we begin recognizing the detached austerity we expect of science. It had become a powerful instrument for seeking truth, but at a price. For science was now no longer at liberty to speak in the light-hearted older language of fables and fairy tales.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

Ashworth, W.B., Jr., Marcus Gheeraerts and the Aesopic Connection in Seventeenth-Century Scientific Illustration. Art Journal, Vol. 44, No. 2, 1984.

G. Gilbert, de Magnete, Magneticisque Corporibus, et de Magno Magnete Tellure, ... (London: Petrus Short, 1600) Dover edition, 1958.

This is a greatly modified version of Episode 261.

Gilbert's version of Gheeraerts' blacksmith