Francis Bacon

Today, science tries to find its way. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Francis BaconFrancis Bacon is one of those famous names of science that we may have trouble connecting with anything in particular. He was born in England three years before Shakespeare. He was educated at Cambridge. At twenty-three he became a member of parliament under Queen Elizabeth. When James took the throne in 1603, he recognized Bacon's huge talents and gave him a series of top government posts. But what sustains Bacon's name is his theory of science. He codified our modern scientific method when he joined a conflict that'd been growing since Leonardo. By Bacon's time, a great gulf separated the old alchemists from the new observational scientists. Leonardo's graphical dissections of nature had pointed the way to modern anatomy, biology, mapmaking and ethnography. Now we had Galileo. But the old alchemical theorists kept on trying to understand the nature of things through pure reason.

Francis BaconFrancis Bacon is one of those famous names of science that we may have trouble connecting with anything in particular. He was born in England three years before Shakespeare. He was educated at Cambridge. At twenty-three he became a member of parliament under Queen Elizabeth. When James took the throne in 1603, he recognized Bacon's huge talents and gave him a series of top government posts. But what sustains Bacon's name is his theory of science. He codified our modern scientific method when he joined a conflict that'd been growing since Leonardo. By Bacon's time, a great gulf separated the old alchemists from the new observational scientists. Leonardo's graphical dissections of nature had pointed the way to modern anatomy, biology, mapmaking and ethnography. Now we had Galileo. But the old alchemical theorists kept on trying to understand the nature of things through pure reason.

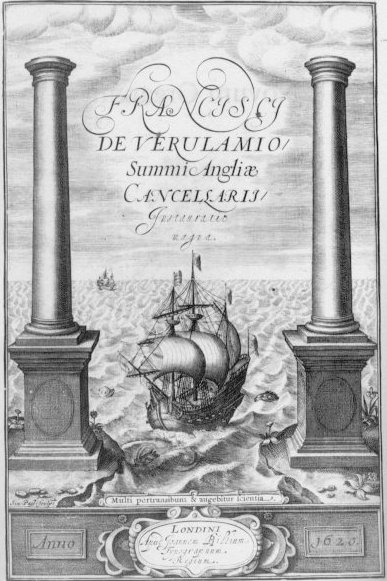

In 1620 Bacon declared war on alchemy in his Novum Organum. In three volumes of that book, he used 192 aphorisms to explain how science should work. They vary from single sentences to short articles. I'll read the first one.

Man, the servant and interpreter of Nature, only does and understands so much as he shall have observed, in fact or in thought, of the course of Nature; more than this he neither knows nor can do.

In other words, Bacon would no longer put up with alchemical deductions. Knowledge not only was to begin with observation; it should also avoid going beyond observation. And he didn't stop there. He went on to say that the evils of current science were the result of too much admiration for the powers of the mind.

After Bacon we amassed a body of facts the alchemists never could have amassed, while theoretical science went fallow. Only an occasional Newton or Leibnitz went where Bacon's methods could not go. Newton was an alchemist who kept quiet about alchemy. But he used his deductive talent to go far beyond mere fact-collecting.

Thinkers began deconstructing Bacon in the early 19th century -- after Romantic poets had insisted that we create nature by dreaming nature. We finally saw that full descriptions of nature had to rest on mental constructions as well as on keen observation. Only then could 19th-century science start moving again.

The problem lay more with Bacon's followers than with Bacon himself. George Bernard Shaw once grumbled that he had nothing against Christianity; it was Christians he couldn't abide. Bacon's followers likewise lost sight of the deeper intent of his ideas.

Most important, it was Bacon who insisted that true science has to be falsifiable. When we stop looking for ways to prove our science wrong, we cease to be scientists. That was Bacon's objection to the alchemists. They reasoned as a debate team might reason; they reasoned to win rather than to inquire. What Bacon insisted on (and what any real scientist must do) is to go where nature directs. A science that begins with its own conclusions is no science at all.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Bacon, F., Novum Organum. (tr. and ed. by Peter Urbach and John Gibson), Chicago: Open Court, 1993. (Many other editions exist, of course. See also the various encyclopedia articles on Bacon.)

You may read the entire text of Novum Organum (which is contained in the writing which goes under the name: The great Instauration) on line at

http://history.hanover.edu/texts/bacon/title.htm

The frontispiece of Bacon's Novum Organum picks

up on the theme of exploring -- of going out and seeing