The Airplane Speaks

Today, the airplane speaks. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

During so-called Bloody April, in 1917, Germany's aeroplanes outclassed and outnumbered the allies. For every German plane shot down, the Allies lost four. The Red Baron, Manfred von Richthofen, then doing his worst, claimed nine percent of the Allied losses.

A month later, Captain Horatio Barber published his book, The Aeroplane Speaks. Powered flight was less than fourteen years old, and Barber was now lecturing on flight to students at the Royal Flying Corps School. Those students were preparing to fly against the Germans and the light-hearted tone of Barber's book is marked contrast with the desperate situation they would face in France.

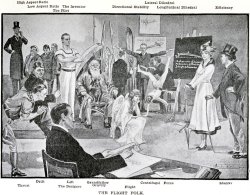

Barber's frontispiece sets the tone. We see sixteen very diverse characters in a drawing room. The names of a tall skinny man and short squat man are High-Aspect Ratio and Low Aspect Ratio. A heavy old man solidly plopped in a chair is Grandfather Gravity, and so on. Efficiency is a pretty lady with a winged hat. These characters, and many others, speak to us throughout the book. Here's the kind of dialog you get:

"Ha! ha!" shouts the Drift, growing stronger with the increased Angle of Incidence. "Ha! ha!" he laughs to the Thrust. "Now I've got you. Now who's master?"

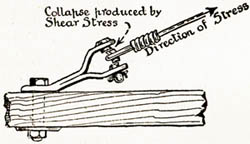

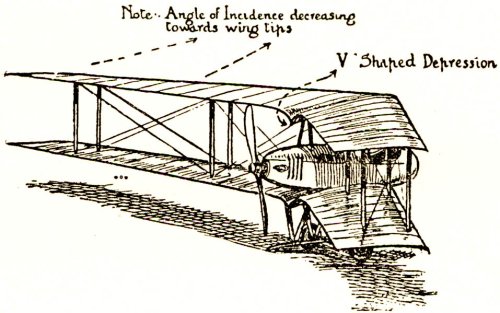

If that sounds just too cute for words, the book itself is very solid. As we keep reading; we find an amazingly complete picture of the aeroplane of WW-I. We learn how struts were anchored, how guy-wires were tied and tensioned, how the complex shapes of wooden propellers were carved. We see how surfaces of those delicate bamboo, canvass, and wire structures were bent -- just so -- to achieve controllable flight.

In his introduction, Barber thanks one Charles Grey for help and support. Grey turns out to've been a very important player. As new technologies come into being they need champions, and Grey was the British champion of aeronautics. England had been slow to develop an enthusiasm for flying. After Grey visited the first Paris air show in 1908, he set out to awaken his country. For his bully pulpit, he created a magazine called The Aeroplane.There he tirelessly advocated for flight.

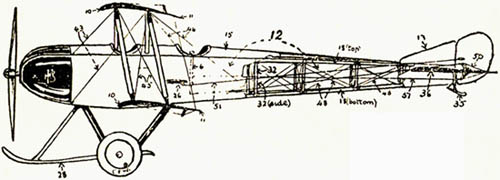

And he did far more for Barber's book than just offer moral support. He also provided 36 elaborate plates, each displaying aeroplane designs by Bleriot, or Curtiss, or Voison, or Wright, or Nieuport, and others we've hardly heard of. Grey turns The Aeroplane Speaks from a merely interesting book into a rare treasure, with that vast inventory of pictorial information.

My father flew the next generation of Nieuports. Now I can now trace the texture of his cockpit, the sailing-ship rigging of the wings, the bounce of wheels grass. Books are strange: Some buffer you -- provide psychic distance from their subjects. Others -- and this is one -- manage to create an unearthly intimacy with an almost-vanished past.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

H. Barber, The Aeroplane Speaks. (New York: Robert McBride & Co., 1917) (All images are taken from Barber's book.)

Click on the thumbnails below for a large images of the Frontispiece (left) and for one of Grey's plates showing a variety of Morane airplane designs: