Running in Place

by Rob Zaretsky

Today, our guest, historian Rob Zaretsky, runs in place. The University of Houston presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

It happened suddenly: the elderly woman walking in front of me stumbled and shouted for help. Instinctively, I broke into a trot, but to no avail. You see, I had forgotten I was on a treadmill -- as was the older woman, clearly unfamiliar with the blinking lights on the dashboard. I simply churned my legs more quickly over the same moving loop of rubber, running in place at the local gym while the poor woman directly ahead was tripped up by technology.

It was an odd moment. We live in a nation, we're told, where more and more citizens are bowling alone. The cubicles at work, the anonymity of city life, and planned isolation of gated suburbs and far-flung exurbs: traditional social ties are disintegrating and Americans have fewer friends then before.

But are bowlers so lonely? The same forces undermining old forms of sociability are creating new forms. Suburban mega-churches offer opportunities for companionship; the countless identical Starbucks nevertheless draw different kinds of faithful clientele; the World Wide Web promises a virtual community for countless surfers.

Take my gym. The scene is familiar: men and women walking, running, climbing and biking on row after row of stationary machines, iPods or cell phones plugged into their ears, their eyes bolted to the banks of television screens floating above.

I often moaned over this brave new world, peopled by an army of human cogs pumping furiously, cut off from one another by our web of electronic IV cords. It wasn't always this way, I thought. At one time, I sweated, therefore I was. Was what? Well, I was part of a team. Basketball, baseball and football were my childhood answers to the Cartesian riddle posed by the Stairmaster.

But another incident took place, upending my bleak assumptions. It involved an older treadmiller who spent his days talking (and cursing) loudly into what I assumed was his cellphone. The curses didn't bother me as much as the broadcasting of what I took to be his private conversations: the spillage of intimate matters into public.

I mentioned this to a neighbor who usually ran nowhere fast in the same part of the gym as I did. We had never before chatted, but seemed to share certain things, like a preference for CNN and crummy sneakers. My neighbor smiled: he was in an aerobics class with the boisterous treadmiller. He was, I was told, quite a nice fellow -- and he was not speaking on a phone, but he had Tourette's syndrome. He couldn't help himself.

I realized that I, too, couldn't help myself -- not just from being an idiot, but also from reaching out to a stranger. As my neighbor and I chatted, I noticed couples, trios, groups involved in conversation. The TVs were reduced to mere wallpaper. We were condemned not just to cardio-vascular time, but also human time. Running in place? Well, yes and no. You see, I had actually reached a finish line, and I'd done it without moving an inch.

I'm Rob Zaretsky, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

R. Putnam, Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. (NY: Simon and Schuster, 2001).

Robert Zaretsky is professor of French history in the University of Houston Honors College, and the Department of Modern and Classical Languages. (He is the author of Nîmes at War: Religion, Politics and Public Opinion in the Department of the Gard, 1938-1944. (Penn State 1995), Cock and Bull Stories: Folco de Baroncelli and the Invention of the Camargue. (Nebraska 2004), co-editor of France at War: Vichy and the Historians. (Berg 2001), translator of Tzevtan Todorov's Voices From the Gulag. (Penn State 2000) and Frail Happiness: An Essay on Rousseau. (Penn State 2001).

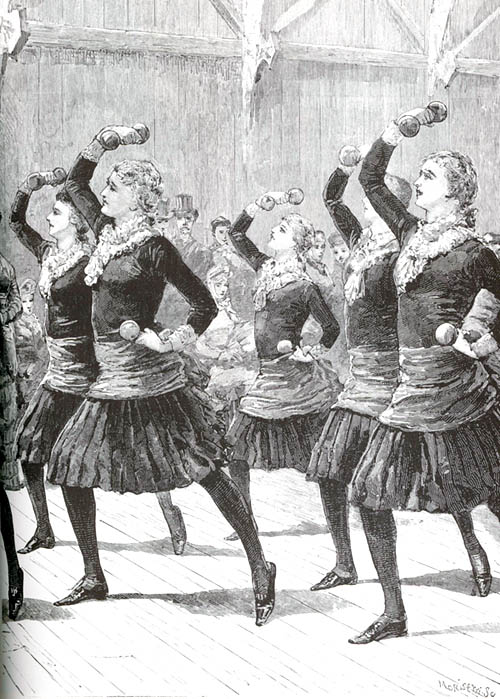

(Clipart from a 19th-C magazine)