Crowds

by Rob Zaretsky

Today, we find our guest, historian Rob Zaretsky, in a crowd . The University of Houston presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Impressionism, the Eiffel Tower, the can-can: these are just a few of our favorite things from late nineteenth century Paris. But crowding out these inventions is the less popular, yet most popular, invention of all: the crowd.

The crowd has always been with us -- has been us -- as long as we've been in cities. The ancient Athenian and Roman democracies rose and fell at the hands of the crowd. The demos, or people, could be transformed by demagogues -- those who manipulated the demos -- into democracy's greatest enemy.

But modern democracies like nineteenth century France faced a different sort of challenge. Of course, the nation's capital, Paris, had always teemed with people ready to revolt: Louis XIV had good reasons to quit the city and build Versailles.

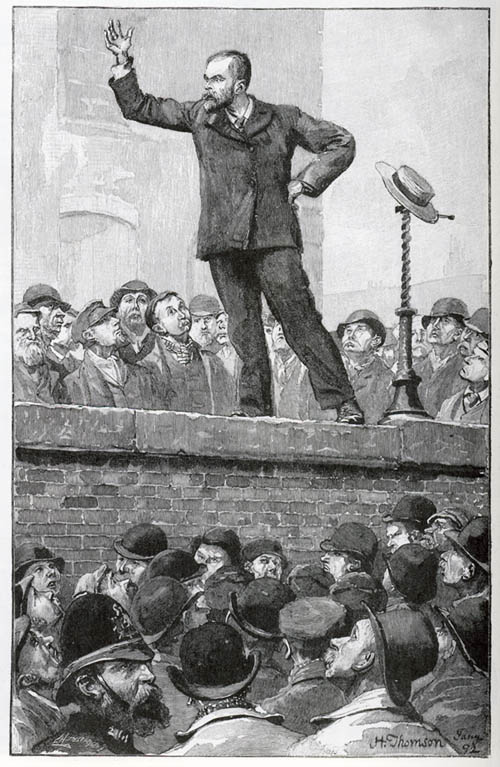

But, by the late 1800s, something new was afoot. The impact of industrialization, the influx of foreigners, the growth of unions and socialist movements transformed the mental landscape of Parisians. New ideological groups, like Action Française and the League of Patriots, anticipated the fascist movements of the twentieth century. The street became the stage for new forms of political theater. At the same time, the cast of extras, the crowd, was now the star. The crowd, the product of progress and justification of a republic, now seemed to threaten both one and the other.

Gustave le Bon was the most influential -- and darkest -- theorist of the crowd. Le Bon lived through the 1871 Paris Commune. The Commune was the civil war between Paris and the rest of France -- a collision between the demands of urban workers and fears of a provincial middle class and peasantry. When Paris was finally subdued, thousands had been killed, the city's center destroyed and observers like le Bon scarred forever.

In his The Psychology of Crowds, published in 1895, le Bon baptized this period the Era of Crowds. When people are pulled from their rural roots and thrown into cities, the framework of traditional beliefs and social hierarchy collapses. Individuals thus become a crowd, a mass galvanized by simple ideas. Charismatic leaders, skilled at using the tools of modern public relations, played the crowd to achieve barbaric ends.

Le Bon was trained as a doctor, and he used medical language to portray this process. He asserted that ideas circulate in the crowd as microbes do in the human body. When absorbed by the crowd, the individual loses control of his reason, forgets his individuality and reverts to his most primitive state. Le Bon claimed that the crowd can be hypnotized to do terrible things, and terrible things it did: Mussolini and Hitler were among Le Bon's keenest students.

Where does one draw the line between observation and obsession, interpretation and invention? It's hard to say. Le Bon's work may well be the disease for which it pretends to be the cure.

I'm Rob Zaretsky, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

Gustave Le Bon, La Psychologie des foules. English translation (translator unknown) is The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind. (NY: Dover, 2002).

Robert Zaretsky is professor of French history in the University of Houston Honors College, and the Department of Modern and Classical Languages. (He is the author of Nîmes at War: Religion, Politics and Public Opinion in the Department of the Gard, 1938-1944. (Penn State 1995), Cock and Bull Stories: Folco de Baroncelli and the Invention of the Camargue. (Nebraska 2004), co-editor of France at War: Vichy and the Historians. (Berg 2001), translator of Tzevtan Todorov's Voices From the Gulag. (Penn State 2000) and Frail Happiness: An Essay on Rousseau. (Penn State 2001).

(Clipart from a 19th-C magazine)