Arabella Buckley & Evolution

Today, another visit with Arabella Buckley. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

In 1879, Arabella Buckley wrote to Charles Darwin, begging him to find a pension for Alfred Wallace. The naturalist Wallace had written his own work on evolution by natural selection while Darwin was hesitating to publish Origin of Species. When Wallace learned of Darwin's book, he stood aside and let Darwin publish first.

Now Wallace was penniless. And, on Buckley's prodding, Darwin went all the way to the prime minister. He managed to secure something called a Civil List Pension for Wallace. I find the whole Darwin-Wallace saga very moving, but today our interest lies not with them. Rather it lies with the remarkable Arabella Buckley.

Buckley was the daughter of a vicar in Brighton, England, born in 1840, and she lived to the age of 88. When she was 24, the great naturalist Charles Lyell, who had helped to get Darwin's and Wallace's ideas published, hired her as his secretary.

It was a learning opportunity, and learn she did. In her thirties, she was editing major scientific treatises. She also began lecturing and writing about biology, for young people. In 1880 and '83, Buckley finished her two best-known books: Life and her Children, and Winners in Life's Race.

Those titles trumpet her early understanding of the deeper meaning of evolution. For she was more than a popularizer. She knew something was missing in the message she was hearing from Darwin's early followers. Natural selection clearly went beyond simple dog-eat-dog. She realized that the real "Winners in Life's Race" had to show the quality of mutual support.

She finishes her book, Life and Her Children, with a powerful paragraph on the role of self-sacrifice in evolution. She correctly suggests that future biologists will:

learn that the "Struggle for Existence," which has taught [insects] the lesson of self-sacrifice to the community, [also teaches that the] devotion of mother to child, and friend to friend ... recognizes that mutual help and sympathy are among the most powerful weapons [of survival].

Twenty years later, Petr Kropotkin would say exactly the same thing in his pro foundly important book, Mutual Aid. And that was also after Buckley had finished her last book, Moral Teachings of Science.

foundly important book, Mutual Aid. And that was also after Buckley had finished her last book, Moral Teachings of Science.

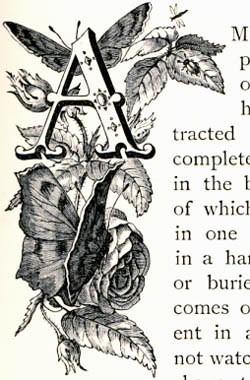

In an odd way, Buckley's medium was a part of her message. Nature is hard, but ultimately beautiful. Throughout her books, are lovely illustrations, and none are as compelling as the initial letters that begin each chapter. Like an illuminated manuscript, she wreathes the letter I in ferns; sea creatures lap about the letter W.

Buckley's evolution is subtle, complex, humane, and then (as now) it offered not a whisper of conflict with her strong religious convictions. In Life and Her Children, she says of evolution,

There has been no halting in this work from the day when first into our planet from the bosom of the great creator was breathed the breath of life, -- the invisible mother ever taking shape in her children.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

A. B. Buckley (Mrs. Fisher), Life and Her Children. (London: Edward Stanford, 1892/1880). (See the book cover below.)

Buckley's books may be read on line here.

R. Colp, Jr., "I Will Gladly Do My Best" How Charles Darwin Obtained a Civil List Pension for Alfred Russel Wallace. Isis, Vol. 83, No. 1, 1983, pp. 2-26.

See also these episodes about Arabella Buckley: No. 943 and No. 3284.

To view all of the Chapter Initial letters from Life and Her Children, CLICK HERE.