Emma Lazarus

Today, UH scholar Dorothy Baker tells us about Emma Lazarus. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

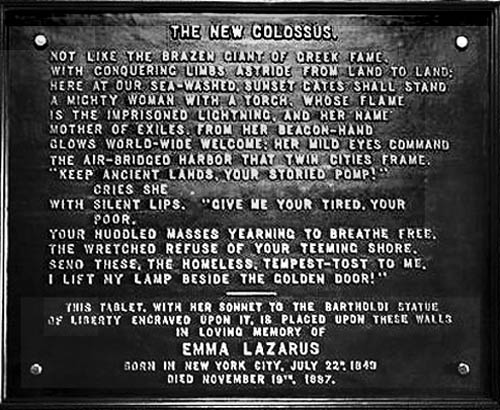

"Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free." These lines from Emma Lazarus's sonnet, "The New Colossus" are inscribed on the Statue of Liberty and imprinted on the American consciousness. But, the lesson of America's welcome

to immigrants that we take from the poem was not part of the original vision of the monument.

The Statue of Liberty is both a work of art and an engineering marvel. To commemorate the one hundredth anniversary of the American Revolution, the French government commissioned Frederic August Bartholdi to sculpt the colossal female figure. The statue was to be named "Liberty Enlightening the World." Bartholdi fashioned the statue as a thin copper sheath the thickness of only two pennies. It could never stand alone. So, he enlisted the aid of the engineer, Gustave Eiffel, designer of the Eiffel Tower. Eiffel created a massive iron pylon surrounded by an equally massive iron skeletal system that would support the copper skin, but allow it to move independent of its structure. The flexibility of the copper sculpture held erect by Eiffel's internal structure contributes to the statue's remarkable grace.

The gift from France had one string. America had to raise funds for the statue's pedestal -- no small feat. Joseph Pulitzer feared that the ship bearing the statue would arrive before we met our obligation. His newspaper campaign inspired a series of fundraisers. One was a poetry auction with America's best writers contributing to the cause -- Walt Whitman, Mark Twain and Emma Lazarus. Lazarus first refused, saying she did not write "to order," but something about the statue inspired this 4th-generation American, descendant of Russian Jewish immigrants. Her poem, "The New Colossus," brought the highest bid -- the then fabulous sum of fifteen hundred dollars.

The gift from France had one string. America had to raise funds for the statue's pedestal -- no small feat. Joseph Pulitzer feared that the ship bearing the statue would arrive before we met our obligation. His newspaper campaign inspired a series of fundraisers. One was a poetry auction with America's best writers contributing to the cause -- Walt Whitman, Mark Twain and Emma Lazarus. Lazarus first refused, saying she did not write "to order," but something about the statue inspired this 4th-generation American, descendant of Russian Jewish immigrants. Her poem, "The New Colossus," brought the highest bid -- the then fabulous sum of fifteen hundred dollars.

In October 1886, when the pedestal was in place and the statue assembled on American soil, President Grover Cleveland unveiled "Liberty Enlightening the World" and claimed with great optimism that the goddess would "pierce the darkness of man's ignorance and oppression" abroad. But, the statue's message to America and the world proved to be as flexible as its structure. Emma Lazarus doubted Cleveland's proclamation. Her pessimism stemmed from ongoing bloody pogroms against Jews in Germany and Russia that made her question anyone's power to reform repressive nations. She countered this dark thought with her vision of the statue -- not as a goddess but a mother. Lazarus named the statue "Mother of Exiles," and this mother would not wait for liberty to enlighten the world. Instead, as the poem explains, she welcomes "tempest-tost" refugees to the safety of our American democracy. The vision of Emma Lazarus reshaped the designs of both the French and American governments, and hers has endured in the American heart.

I'm Dorothy Baker, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

Dorothy Z. Baker is Associate Professor of English at the University of Houston. A specialist in American literature and culture, she is the author of Mythic Masks in Self-Reflexive Poetry and the forthcoming America's Gothic Fiction: The Legacy of Magnalia Christi Americana, and the editor of Poetics in the Poem and The Soft and Silent Communion: The Spiritual Narratives of Sarah Pierpont Edwards and Sarah Prince Gill. Baker was awarded the UH Enron Teaching Excellence Award and the College of Liberal Arts and Social Science Master Teaching Award.

M. Cavitch, Emma Lazarus and the Golem of Liberty. American Literary History, Vol. 18. No. 1, 2006, pp. 1-28.

H. E. Jacob, The World of Emma Lazarus. (New York: Schocken Books, 1949).

M. Trachtenberg, The Statue of Liberty. (New York: Viking, 1976.)

M. Twain, Mark Twain Aggrieved: Why a Statue of Liberty When We Have Adam! New York Times 4 Dec. 1883. Vol. 2.

B. R. Young, Emma Lazarus in Her World: Life and Letters. (Philadelphia and Jerusalem: The Jewish Publication Society, 1995).

The outro music is from Her Beacon Hand, a section of Michael Horvit's Choral Symphone for the Moores' School Symphony Orchestra & Festival Orchestra, The Mystic Flame. Franz Anton Krager, Conductor, Albany Records, Troy533, Track # 7.