Fairy-land of Science

Today, a scientist talks to us about magic. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

I've just come across an old book, The Fairy-Land of Science. Elves and water sprites dance across its cover. It's a children's book, written in 1878 by Arabella Buckley -- filled with fine engravings that capture a child's world of fantasy and imagination. A poem about fairies on the title page says,

... the young and fresh imagination

Finds traces of their presence everywhere.

The text agrees: "If you have the gift of imagination, come with me, and we will look for the invisible fairies of nature." But the book is not what it seems to be. "We shall see," Buckley says, "that [particles of water vapor in the air] are held apart by heat, one of the most wonderful of our forces or fairies".

That sort of thing gets an historian's attention. The word "force" had just recently become common currency for the unexplainable absolutes of science -- gravity, energy, magnetization. And only a few years earlier, James Clerk Maxwell had given us a kinetic theory of gases to explain how air holds water.

Arabella Buckley was giving children the latest thinking. And since those forces still lie beyond understanding, they might as well be exerted by fairies. I searched out more of her books. The title of her optics text is Through Magic Glasses.

Buckley was born in Brighton, England, in 1840 -- a vicar's daughter. At 24 she went to work as secretary to Charles Lyell. Lyell had been a teacher to Charles Darwin. He was a great student of geological history. Buckley worked for him 'til he died in 1875. Then she began lecturing and writing on science.

One of her early books was on evolution. The title, Winners in Life's Race, or, The Great Backboned Family, tells us that she had joined the Victorian battle that was then pitting science against religion. But she didn't see any sides to be taken. She was a confident evolutionist who could write,

"the forces of nature, whether apparently mechanical or intelligent, are one and all the voice of the Great Creator."

She was 44 when she married a doctor named Fisher. Then she violated Victorian custom by continuing to write under her maiden name, Buckley. Her so-called children's books are completely solid texts on botany, geology, chemistry and physics.

And so wonderfully illustrated! "Science is full of beautiful pictures, of real poetry, and wonder-working fairies," she wrote. Her pictures -- of flowers and stalactites, of geologic faults and ocular optics -- tell us she was serious about her fairies. They speak the magic she'd seen where we forget to look for magic: in lenses, clouds, and crystals -- in the gossamer tracery of the whole living world around us.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Buckley, A.B., The Fairy-Land of Science, London: E. Stanford, 1887 (written in 1878 and first published in 1879).

Buckley, A.B., Through Magic Glasses and Other Lectures: A Sequel to 'The Fairy-Land of Science'. London: E. Stanford, 1880

Buckley, A.B., Winners in Life's Race, or, The Great Backboned Family, London: E. Stanford, 1882

Buckley, A.B., Life and Her Children: Glimpses of Animal Life from the Amoeba to the Insects. London: E. Stanford, 1880.

I am grateful to Margaret Culbertson, UH Art and Architecture Library, for bringing Arabella Buckley Fisher and her remarkable books to my attention.

Image courtesy of Special Collections, UH Library

Cover of The Fairy-Land of Science, 1878

Image courtesy of Special Collections, UH Library

A more formal image of science from The Fairy-Land of Science, 1878

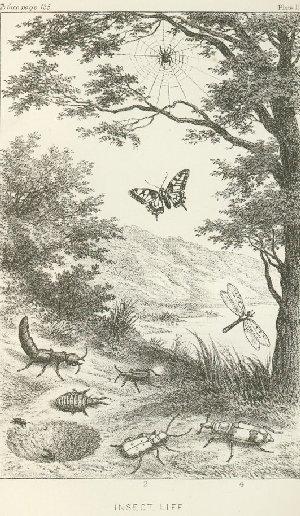

Image courtesy of Special Collections, UH Library

One of many studies of insects from Life and Her Children, 1889