A View Through Schenectady

Today, we look for American history in a single town. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Let me ask: how do we best learn history? History usually means some sort of trip through time, but where to take that trip? Should we trace governments, technology, or art -- firearms, Denmark, or peerages? We'll never see history whole, but any one of these paths through time will tell us what other paths will not.

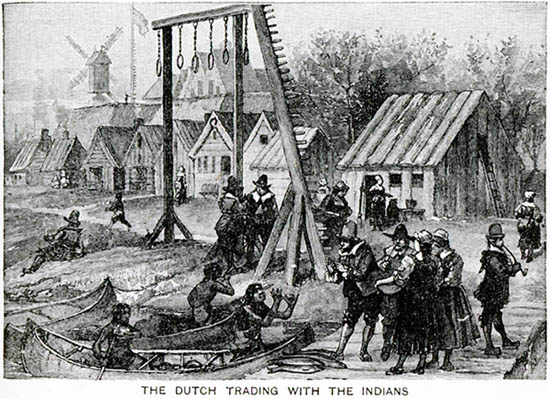

I've been reading a pictorial history of Schenectady -- only that one town -- but there was America itself unfolding. And with good reason: Schenectady nests in a bend of the Mohawk River at the head of the Mohawk Valley, just west of the confluence of the Mohawk and the Hudson. In the seventeenth century, this is where Indian and Colonial trade goods moved by canoe.

By then, New York was the home of the vast Iroquois Federation of five nations: The Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca. The Tuscaroras would soon move up from North Carolina and become the sixth. French, English, Dutch and other colonists were living along the Hudson and Mohawk. The name Schenectady came from a Mohawk phrase for beyond-the-pine-plains -- S'quan-ho-hac-ta-de.

The town was first built by Dutch settlers in the mid-17th century. It was the Wild West three-and-half centuries ago -- traders and tradesmen on the far frontier of Colonial America, living in an uneasy balance with the diverse Iroquois.

A British garrison moved in among the Dutch to protect trading British interests in 1670 -- one more red flag in the face of the French. Twenty years later two-hundred French and Indians burned Schenectady to the ground, killed sixty people, took 27 captives and freed the remains of the town's hundred or so occupants.

You'd think that might've been the end of it. But, by 1705, the Dutch were back, and the British built a substantial fort there. As tensions between the British and French rose, they divided the Iroquois nation. Some tribes and nations sided with the French, some with the British. By 1755, mere skirmishes had become the all-out French and Indian War.

France lost the war. But all this Colonial combat would come to a head, a few years later, in the American Revolution. It would be fed by alliances and enmities that'd festered along the Hudson and Mohawk Rivers. And, after the Revolution, the Iroquois Federation would vanish, its-now scattered nations pushed off to the west.

No more S'quan-ho-hac-ta-de. Schenectady was about to find a new role. We needed a trade route to the Great Lakes and, by 1825, the Erie Canal followed the Mohawk from Albany and Schenectady to the west. Industry followed -- railways and, eventually, General Electric. But that's another story for another day.

My fascination lies with the way a single town, through an accident of geography, became one taproot of the American saga. History is always the selection of one window or another. And Schenectady is a window through which we see a very great deal.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

L. Hart, Schenectady: A Pictorial History. (Scotia, NY: Old Dorp Books, 1984).

(From E. S. Ellis, History of Our Country. Vol. 1 (Indianapolis, IN: J. H. Woolling & Co.) pg. 155.

For a map of the region during the 17th and 18th centuries, click on the thumbnail to the right. [From R. G. Thwaites, France in America: 1497-1763. The American Nation: A History, ed. A. B. Hart (New York: Harper & Brothers Pubs, 1905.) pg. 204 facing.]

For a map of the region during the 17th and 18th centuries, click on the thumbnail to the right. [From R. G. Thwaites, France in America: 1497-1763. The American Nation: A History, ed. A. B. Hart (New York: Harper & Brothers Pubs, 1905.) pg. 204 facing.]