We Are the Machines' Media

Today, our machines speak through us. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

We talk so much about technology in specifics that we can forget the way our machines form metaphorical vocabularies in our lives -- both metaphors of function and metaphors of form. I've talked about many of the metaphors of function on this program:

The analog clock face is a metaphor for the path followed by the sun across the daytime sky. The book is our metaphorical mentor while the computer is our metaphorical servant, and those are two functions that we will not interchange -- hence the staying power of the book in the face of the computer. Doors become our metaphors for both welcome and rejection, and so on.

Those are all metaphors of function, but we also take the pure form of our machines into our lives as metaphorical imagery to build upon. Those forms can become so distinctive that, once we absorb them, we refer other things to them.

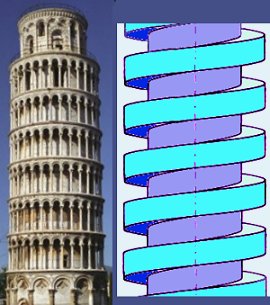

Of course, we vary in our ability to see small articulations in the form of machines, just as we vary in our ability to distinguish colors, musical pitches, or faces. Yet those images, once formed, are very strong. Toothed gears, screw threads, the piston/cylinder arrangement, trussed bridges or roofs -- those all reflect into our subsequent architecture and design.

Once we understand the beauty of function that an artifact represents, it reveals beauty of form. What is the Tower of Pisa, with it spiral outside staircase, but a great lag screw extending into the sky? Is the open book anything more than a physical doorway bidding welcome to our minds?

Once we understand the beauty of function that an artifact represents, it reveals beauty of form. What is the Tower of Pisa, with it spiral outside staircase, but a great lag screw extending into the sky? Is the open book anything more than a physical doorway bidding welcome to our minds?

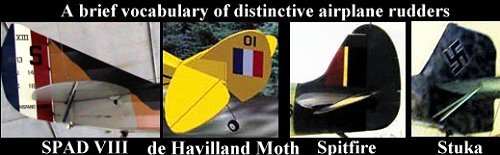

Details of specific machines engage us, just as the features of specific faces, birds, or flowers, do once we've learned to see them. The rudder of de Havilland's early airplanes is so distinctive that, once digested, it's remembered. Those who lived through the Battle of Britain are unlikely to forget the distinctive S-shaped leading edge of the Spitfire's rudder. No one who survived Guernica in 1937 will forget the Stuka dive bomber's square rudder.

If you know automobiles, you'll smile when I say "postwar Nash headlights," "1959 Cadillac tailfins," or "prewar Packard radiators." Few of us have encyclopedic knowledge of autos, airplanes, or screw threads. Yet our lives are all surrounded by the many engines of our ingenuity, and their forms touch us in subtle ways.

More recently, as our machines become more intimately tied directly to our senses, they find different avenues into our subconscious. We hardly see our loudspeakers, but our sense of that machine is our sense of the sound we hear. Computer screen manufacturers understand that. They increasingly make their physical screens as invisible as possible, so that we see only the picture.

And so our machines spread their influence through the medium of our minds. That might seem a strange state of affairs, but it is what happens. We really are the media by which our machines speak.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.