The Internet of Tubes

by Andrew Boyd

Today, guest scientist Andrew Boyd and the Internet of Tubes. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Alaska senator Ted Stevens made himself a media target with a shockingly incoherent statement about the Internet. Chairman of the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation, Stevens was lambasted by comedians and the press for using phrases like "an Internet was sent by my staff." His most celebrated remark was: "The Internet is not something you just dump something on. It's not a truck. It's a series of tubes."

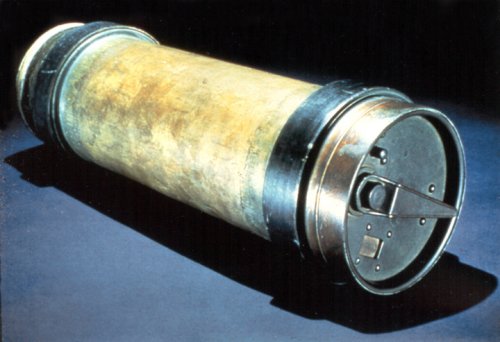

Crazy as the idea of "tubes" sounds, is it really such a bad analogy for the Internet? It calls up the pneumatic tubes used at drive-up banks to transport paperwork to and from cars. Put your documents in a sealed canister, push a button, and whoosh -- the canister goes flying through a tube to arrive behind bulletproof glass. As a child I remember watching pneumatic tubes being used to transport documents high over the interior of warehouses, relishing every twist and turn.

Few people realize that pneumatic tubes were the pinnacle of late nineteenth century communication technology. One of the earliest commercial applications dates to 1853, when a tube was used to transfer messages between a private telegraph office and the London stock exchange, 200 yards away. But it was not until 1870 when J. W. Willmot introduced technology making it possible for more than one canister to travel in a tube at the same time, that tube networks really began to grow.

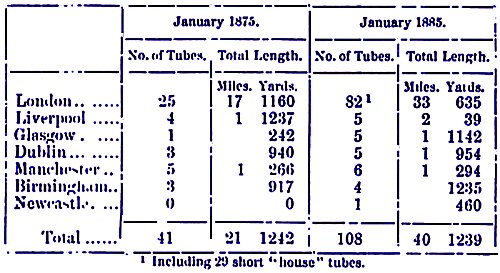

Within four years of Willmot's invention, tubes connected London's Central Telegram Office with the many district post offices, and the expanding system handled four-and-a-half million messages a year. Twelve years later, the London system stretched over 34 miles and was powered by four 50 horsepower engines. Canisters made of gutta percha -- the same material then used to make golf balls -- were wrapped in felt and traveled at an average speed of 20 miles an hour, propelled by pressure differences at the two ends of a tube. Throughout all Britain, including many smaller cities that had their own tube networks, the year 1886 saw over 50 thousand messages delivered by tube each day -- over 18 million per year.

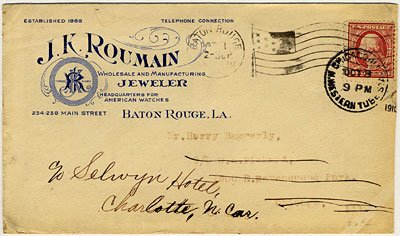

The great cities of mainland Europe weren't far behind. Pneumatic tube systems were developed in Berlin, Munich, Vienna, Prague, Rome, Naples, Milan, and Marseilles. One of the world's great systems was in Paris, where the combined tube length was over 200 miles. Formally known as the "Carte Pneumatique," Parisians simply called it the "pneu." Originally designed to carry only transcribed telegrams, the pneu was eventually opened to the general public as an alternative to the postal system. Parisians used it for much the same reason we use the Internet today: speed of delivery. Of course, if too many people wanted to send messages at the same time, the system would become clogged with mail and slow down.

So, in the end, perhaps we shouldn't be so hard on Senator Stevens. After all, he wasn't entirely wrong. He was just a century behind the times.

I'm Andy Boyd at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

MacGregor, J., Pneumatic Dispatch. Encyclopaedia Britannica, Vol. 18, pp. 95-96, 1957.

Hayhurst, J. D., The Pneumatic Post of Paris. The France and Colonies Philatelic Society of Great Britain, 1974 (see this online article by J.D. Hayhurst).

See also: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pneumatic_tube

A period pneumatic mail capsule (Courtesy of the National Postal Museum).

Cover for a pneumatically posted letter (Courtesy of the National Postal Museum).

1894 Encyclopaedia Britannica statistics on the early growth of pneumatic postal tubes.