Of Mentors and Servants

Today, we wonder what books have that computers cannot replace. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

I want to try an idea on you. I've been talking with friends lately about the fate of books. Will some form of electronic book replace paper books during our lifetimes?

In another episode I argue that books are too perfect a technology to be replaced. As computer screens become more readable -- as memory and speed increase -- they'll bypass paper books but not replace them. Computers will create such a different kind of reading experience that books will have to remain.

That's fine, many people tell me, but they still wonder what paper books have that mature electronic books won't soon have as well? In one recent conversation it dawned on me what sets books apart: it is that books are mentors and computers are servants.

We all switch between the roles of parent and child. We need some control over things around us. But we also need to submit to other people's knowledge. In some things, we should play the parent. In others, we'd better know how to be a child.

And the child says, "Tell me a story." The story we choose might be a Gothic novel. It might be a math textbook. In either case we have to give ourselves over to the storyteller if we hope to profit from the story. We do that when we read a book, go to the theater, even listen to a concert.

Computer communications are quite another matter. Once we master a computer, it does our bidding. We say, "Go and do. Buy me an airplane ticket. Give me a stock quotation. Tell me if the library has a book. Pass this message to a friend." The computer dances to our tune. We are in control.

When you and I go to the computer for text material, it's to look things up. It's not to let words wash over us nor to touch and feel paper. The computer is far better than a book if you want to find things. Insofar as paper books function as simple repositories of fact, they've already given way to computers.

But the sort of book we submit ourselves to will remain at its best when it's written out and uncontrollable -- when it's on paper. It's an important omen that as stories appear on computers they begin offering readers control over the story. It's no accident that you can already buy computer books which let you dictate the course of the plot.

To learn, we become as children. We seek out our own ignorance. Now and then we follow the mind of someone who knows what we do not. We yield to the rhythm of the storyteller. Printed books let us lay control aside for a while. That's the wonderful gift books offer. The electronic media, for all they give us, are headed in exactly the opposite direction.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

See Episodes 708 and 874 for more on the fate of the paper book. This idea evolved out of conversations with Heather Moore and several suggestions by Pat Bozeman, both from Special Collections, UH Library.

There is no frigate like a book

To take us lands away,

Nor any coursers like a page

Of prancing poetry.This traverse may the poorest take

Without oppress of toll;

How frugal is the chariot

That bears a human soul!

Emily Dickinson Part I, Life, XCIX

Does it afflict you to find your books wearing out? I mean literally. . . . The mortality of all inanimate things is terrible to me, but that of books most of all.

William Dean Howell

Letter; April 6. 1903

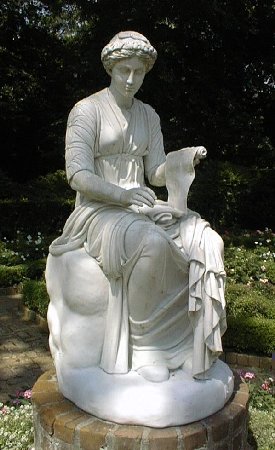

Photo of a statue at the Bayou Bend Museum in Houston, by John Lienhard