Ruth Elder

Today, an odd postcard. The University of Houston's college of engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Sorting through accumulated papers yesterday, I found a 1930 postcard that my mother had kept. It shows an airplane with American Girlwritten on its side, and a woman named Ruth Elder. I went off to learn about Elder and a remarkable pioneer emerged.

She'd been many things -- movie star, pilot, activist. When Lindbergh flew from New York to Paris, she promptly vowed to be the first woman to fly the Atlantic, and signed up for flying lessons.

She persuaded a group of businessmen to sponsor her, and she bought a new Stinson Detroiter airplane for the trip. The Detroiter was a single-engine,

high-wing monoplane. As a passenger carrier, it seated six people. Or it could haul a goodly load of airmail. Its normal range was only seven hundred miles but, with modification, it could hold enough fuel for a much longer trip.

A scant five months after Lindbergh's flight, Ruth Elder and her instructor, George Haldeman, set out from Lakeland, Florida toward Portugal. That was eighteen percent further than Lindberg's flight, but it passed over the Azores along the way.

Good thing it did; Haldeman and Elder suffered an oil pressure failure and had to ditch in the ocean near the islands. A passing Dutch tanker found them floating in special inflatable rubber suits they'd taken along. So they both lived to tell of it. And Elder had been the first woman to fly most (if not all) of the Atlantic.

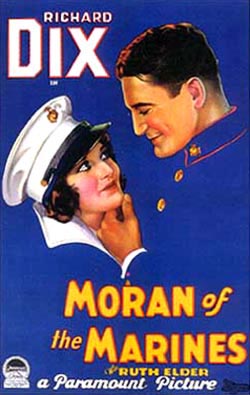

America took notice of her. She was given the female lead in the 1928 silent movie, Moran of the Marines. She played opposite Richard Dix. He acted for thirty years and was nominated for an Oscar. Jean Harlow was also in the movie -- doing her first bit part.

America took notice of her. She was given the female lead in the 1928 silent movie, Moran of the Marines. She played opposite Richard Dix. He acted for thirty years and was nominated for an Oscar. Jean Harlow was also in the movie -- doing her first bit part.

But Elder wanted to fly and, in 1929, she was back in the air. This time, she and twenty other women took part in the first Women's Air Derby -- a nine-day race, in nine segments, from Santa Monica to Cleveland. Amelia Earhart also competed, but Louise Thaden won the race. Elder was among fourteen finishers. She'd had to make one forced landing in a field of cattle. "Oh God, please let them be cows," she prayed as she touched down.

Another flier, Marvel Crosson, was killed trying to bail out of a crash, and a prominent Texas oilman named Haliburton said, "Women have been dependent on men for guidance for so long that when they are put on their resources they are handicapped."

The women saw it differently. Two-and-a-half months after the Derby, they formed a group called the Ninety-Nines. They went to all 117 licensed women fliers in America and managed to recruit ninety-nine of them. They've pushed women's involvement in flying ever since. And Ruth Elder was a member until her death in 1977.

So I look again at my postcard and I notice two things. First, a thumbtack hole where my mother, who didn't even drive a car, had hung it on the wall. The other is Elder herself. She was nearly the same age as my mother, and she could have passed for her sister.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

J. Lomax, Women of the Air. New York: Ivy Books, 1986, pp. 68-79.

For more about Ruth Elder, click here.