"Modern" Blacksmithing in 1902

Today, we learn blacksmithing. The University of Houston's college of engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

My junior year in engineering included a course on forging and welding -- a course in practical blacksmithing. I still have the center punch and the offset screwdriver that I hammered from glowing red iron, and then surface-hardened in a bucket of cold water.

That was 1949, and even then it seemed anachronistic. One bought center punches and screwdrivers at the hardware store; one did not make them. Now I find a book published in 1902: Manual of Modern Blacksmithing. I'm caught off guard, seeing the word Modern next to Blacksmithing. Yet the book brings up powerful tactile memories of the pleasure that course once gave me.

The author, named only as An Expert Blacksmith, wastes little breath on explanation. His scant discussions of carbon content and different irons and steels appear only in the last chapter. A few remarks tell about the "fiber" of iron and bad practice that can "crystallize" it. (You and I are frustrated when such terms aren't explained by looking at the metal's fine structure.)

Indeed the two hundred pictures festoon the book with forges, hammers, and tongs. He describes forge-welding and the process called upsetting. We see examples of hammered crankshafts, levers, and connecting rods while the one item we most expect to see, the horseshoe, never appears. Perhaps this really is modern smithing after \ all -- smithing for the new age of the automobile.

So I turn to that last chapter, Manipulating Steel at the Forge. Common steels are low-carbon alloys of iron that lend themselves to a blacksmith's means for controlling texture -- annealing, hardening, and tempering. Annealing yields the softest possible steel. One way to do it is to surround the steel with hot ashes, then let it cool very slowly along with the ashes. To harden the surface of steel, we heat it red-hot, then rapidly quench it in water, oil -- or even mercury (if we can afford it.)

Tempering lies between annealing and hardening. We heat steel to less than dark red -- where its surface takes on an opaque hue anywhere from straw yellow to dark purple. Then we quench it in air or some liquid. That process leaves steel somewhat hardened, but still tough and flexible. We do it differently, depending on whether we're making springs, straight razors, or axe-heads.

So much technique -- even delicacy -- as this book seeks to form a bridge between the medieval world and one where steel products are stamped out in factory lines. Those of you who (like me) are of a certain age, were raised reciting Longfellow:

Under the spreading chestnut tree

The village smithy stands;

The smith, a mighty man is he, ....

His brow is wet with honest sweat,

Well, he certainly was to be reckoned with, even while his horse-shoes and wheel rims gave way to crankshafts and connecting rods -- in this last-gasp, thoroughly-modern treatment of his trade.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

Manual of Modern Blacksmithing, (the author is identified only as an expert blacksmith) Chicago: The Progressive Publishing Co., 1902.

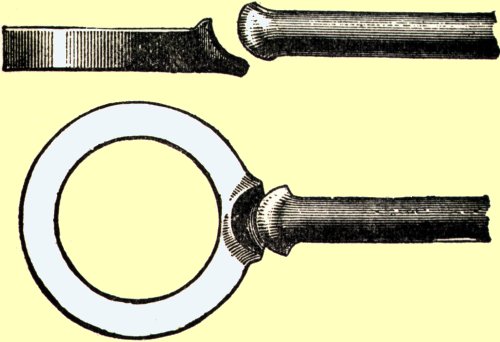

Two forged pieces about to be forge-welded

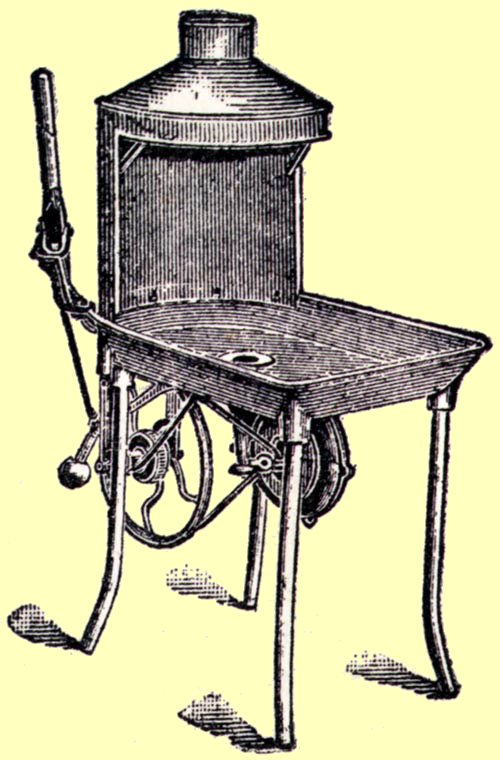

A small home made portable forge

A medium-sized commercial forge

THE VILLAGE BLACKSMITH

Under the spreading chestnut tree

The village smithy stands;

The smith, a mighty man is he,

With large and sinewy hands;

And the muscles of his brawny arms

Are strong as iron bands.

His hair is crisp, and black, and long,

His face is like the tan;

His brow is wet with honest sweat,

He earns whate'er he can.

And looks the whole world in the face,

For he owes not any man.

Week in, week out, from morn till night,

You can hear his bellow blow;

You can hear him swing his heavy sledge,

With measured beat and slow,

Like a sexton ringing the village bell,

When the evening sun is low.

And children coming home from school

Look in at the open door;

They love to see the flaming forge,

And hear the bellows roar,

And catch the burning sparks that fly

Like chaff from the threshing-floor.

He goes on Sunday to the church,

And sits among his boys;

He hears the parson pray and preach,

He hears his daughter's voice,

Singing in the village choir,

And it makes his heart rejoice.

It sounds to him like her mother's voice,

Singing in Paradise!

He needs must think of her once more

How in the grave she lies;

And with his hard, rough hand he wipes

A tear out of his eyes.

Toiling, - rejoicing - sorrowing,

Onward through life he goes;

Each morning sees some task begin,

Each evening sees it close;

Something attempted, something done,

Has earned a night's repose.

Thanks! thanks, to thee, my worthy friend,

For the lesson thou has taught!

Thus at the flaming forge of life

Our fortunes must be wrought;

Thus on its sounding anvil shaped

Each burning deed and thought.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow