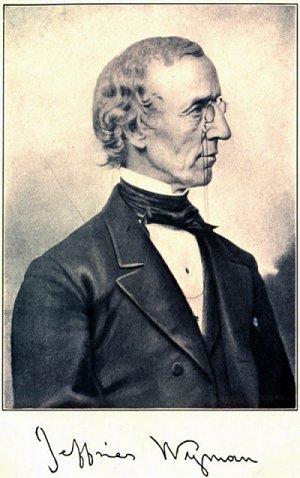

Jeffries Wyman

Today, a quiet academic. The University of Houston's college of engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Jeffries Wyman was born in 1814, near Boston. He finished Harvard Medical School at 23 and he went to work at many things. He became curator of the new Lowell Museum, assistant physician at Mass General, anatomy demonstrator at Harvard. He even served in a volunteer fire department. He also made the European tour expected of rising young American academics. Finally he gained teaching posts -- first in Virginia, then Harvard. Meanwhile, his focus shifted from medicine to comparative anatomy and anthropology.

From 1843 until to he died at sixty, Wyman played sedate counter-point to the furious scientific revolution surrounding Darwin's Origin of Species. According to Oliver Wendell Holmes, he suffered a lifelong chronic lung problem. It began as pneumonia when he was a student and it finally killed him. Yet he managed to work tirelessly. He did fieldwork both here and abroad. He wrote and published hundreds of articles, mostly in anatomy and anthropology.

From 1843 until to he died at sixty, Wyman played sedate counter-point to the furious scientific revolution surrounding Darwin's Origin of Species. According to Oliver Wendell Holmes, he suffered a lifelong chronic lung problem. It began as pneumonia when he was a student and it finally killed him. Yet he managed to work tirelessly. He did fieldwork both here and abroad. He wrote and published hundreds of articles, mostly in anatomy and anthropology.

None of that made Wyman loom large in the long lens of history. He was, you might say, a top-of-the-line, non-famous scientist. For science can take two forms. On the one hand, it is the periodic upheaval in the way we understand the world we live in. But it's also the steady emergence of a body of fact.

Wyman was an empiricist, a keen observer, and an artist. (His fine ability with a sketchpad reminds us of Audubon.) He was also a questioner. He corresponded with Darwin and Darwin used his data. But Wyman himself simply let the truth of evolution by natural selectionplay out. He didn't champion it -- he just wrote about what he saw, and let evolution rise like cream.

He was a theist, but he also kept his mouth shut about that. His job was to be lucid in transmitting what he knew. It was to define areas of doubt and to keep himself out of the picture.

He's best known for doing the first study of Gorillas. He identified them as a species separate from orangutans. He coined the word gorilla. His famous Harvard colleague Louis Agassiz was trying to prove that Black and White races were separate creations. Wyman simply pointed out that gorillas and humans were fundamentally different. Black and White people, on the other hand, showed almost negligible differences from one another.

That's how Wyman worked: Lay out the facts and avoid the polemics. William James studied with both Agassiz and Wyman; he held each in high affection, but he had to acknowledge that Agassiz was full of fascinating ballyhoo. Wyman taught him to be a scientist.

We can't all be Faradays or Einsteins. We need models of something closer to our grasp. Poet James Russell Lowell under-stood. When Wyman died, he wrote this:

Nothing to count in World, or Church, or State,

But inwardly in secret to be great ...

To widen knowledge and escape the praise, ...

To toil for Science, not to draw men's gaze,

That was Wyman. He too helped change the world but, when he was done, he left the stage. He didn't linger in his own light.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

A. Hunter Dupree, Wyman, Jeffries. Dictionary of Scientific Biography(C.C. Gilespie, ed.) New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1970-1980.

B. G. Wilder, Jeffries Wyman: Anatomist. Leading American Men of Science, New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1910, pp. 171-209.

For a sample of Wyman's work, see J. Wyman, Fresh-Water Shell Mounds of the St. John's River, Florida (Intro. By Jeremy A. Sabloff) New York: AMS Press, Inc., 1973.

And, by the way, J. R. Lowell also did a poem for Agassiz, when he died. His words, however, had quite a different ring. He included, for example, the lines,

Three tiny words grew lurid as I read,

And reeled commingling: Agassiz is dead!

I've glossed over one issue in the text above. What Wyman actually said about gorillas and races grates upon our ears. However, one must remember what a racist culture surrounded him. Here, in 1859, he gently nudges that culture in the right direction:

[the] difference between the cranium, the pelvis, and the conformation of the upper extremi-ties in Negro and Caucasian sink into comparative insignificance when compared with the vast difference that exists between the conformation of the same parts in the Negro and the orang. Yet it cannot be denied, however wide the separation, the Negro and orang do afford the points where man and brute, when the totality of their organization is considered, most nearly approach each other. (see Hunter, above.)

Those were tough times. Wyman tips his hat to prevailing racist beliefs, at the same time he undermines them.

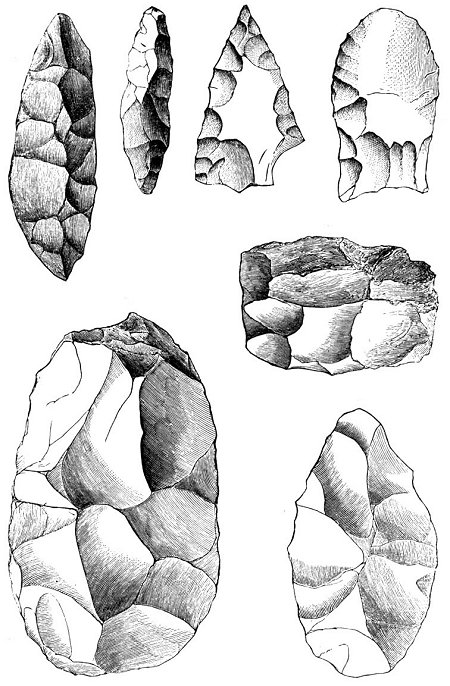

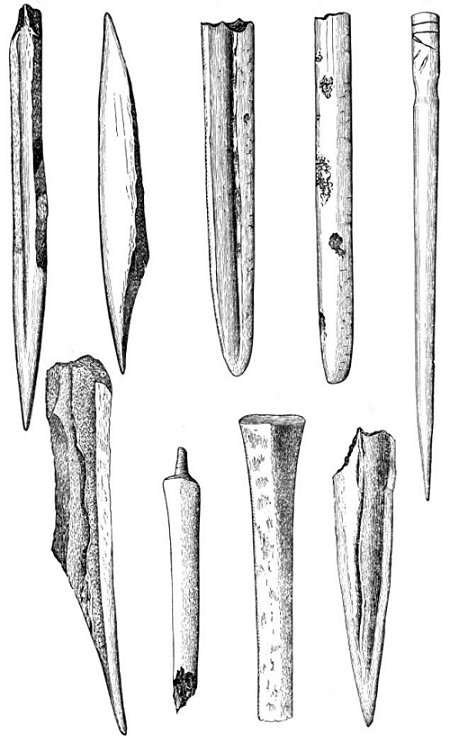

Two plates of Wyman's exquisitely detailed drawings from Fresh-Water Shell Mounds ... follow: