1900 -- The Year

Today, 1900 -- the year. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

How else to observe my nineteen-hundredth episode than by looking back at the year 1900 -- the year our Earth shifted on its axis. We were just beginning a vast scientific, artistic, and technological revolution. Yet we read just how invisible that tsunami of change was, when we open the 1900 Century Magazine.

We were at peace. We'd just won the Spanish American War at a cost of 20,000 Filipino soldiers, and ten times that number of Filipino civilians. But we (here in the United States) had got off with 4200 dead and a lot of new real estate. A year later, the war was no longer on our minds.

Instead, we read long serialized articles on Napoleon and Cromwell. Admiral Dewey is barely mentioned in an article on how to mount a successful parade. The article offers Dewey's postwar parade as a fine example. And it ends by noting that electricity promises great improvements in the traditional torchlight parade.

Throughout the issues are scattered art and poetry. The poetry generally sounds like this:

See, as we climb the woodland way,

Yon rose-tinged blossoms shine!

And this, more white than acolyte

That guards a hidden shrine!

Ever so pastoral and pretty -- none of the hard edges being developed by the turn-of-the-century poets we know today -- no W. B. Yeats, Stephen Crane, or A. E. Housman here. Several articles look back to Tennyson, Browning, and Lowell as model poets.

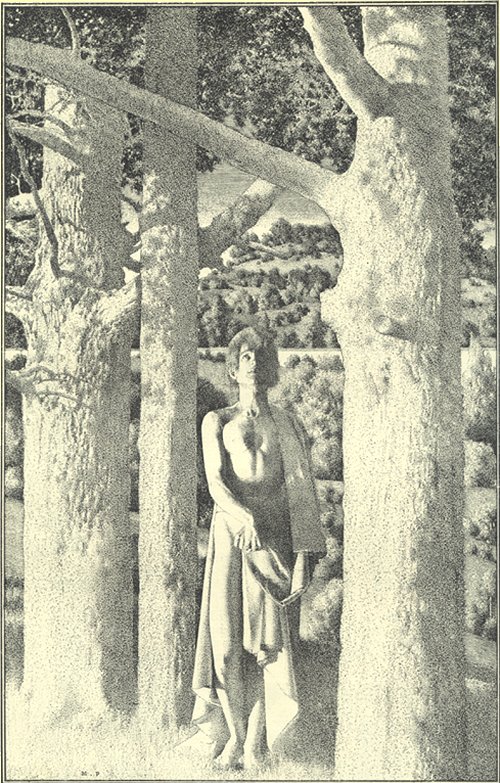

The art is equally retro -- rich nostalgic salon art. No impressionists; none of the first modern artists. The border trimming hasn't quite made it to art nouveaux. A young Maxfield Parish has illustrated a sentimental poem about praying in a forest. The Pre-Raphaelites are the clear model of what art should be.

One real harbinger of the new century stands out like a sore thumb. Nikola Tesla has a long article on The Problem of Increasing Human Energy. He talks about many things, including several schemes for using solar energy. He also devotes several pages to his new notion of wireless telegraphy. Here is the theoretical foundation of radio. A year later, Marconi would build the first successful radio. Meanwhile Century Magazine presents Tesla, more as a colorful scientist than as a serious harbinger of any future.

These lovely old issues, bathed in sentiment, become a serious warning as you and I set about to build our new century. We're no more able to see what's coming than these writers were. Like them, we try to extrapolate a future from what we've seen in the last twenty years -- computers, biology, dark matter.

The true future is already among us, but it's very hard to pick out from a thousand hints. To see how that works, look at one more remarkable verse from the magazine -- one in which the poet could well be steering us away from the relativity theory, just about to blindside us. He says:

Time and Space and Number flow

Ever onward; none shall know

Whence they come, or where they go.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

Century Magazine, New York: Vols. LIX and LX, November 1899 through October 1900. (Thus I've fudged by two months in the 1900 identification of the episode.) The poetry quotes are, respectively, from In the Southern Alleghanies, by Marion Pelton Guild, November 1899; and The Infinites, by Curtis Hidden Page, March 1900.

Maxfield Parrish's illustration for A Hill Prayer by Mirian Warner Wildman

Century Magazine, December, 1899.