The Timber Square Set

Today, the timber square set. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Off in the mountains of Western Montana is the town of Philipsburg. And I want to tell you how it got its name. That story might well begin in Agricola's sixteenth-century treatise on metallurgy, De Re Metallica.

Book V of Agricola tells how to do underground mining, and it's pretty complete. When you dig for ore you have to shore up the tunnels so they won't cave in. Agricola describes techniques, well-developed by 1550, for setting support timbers in mines.

Three hundred years later, in 1859, silver was discovered in Virginia City Nevada. Those Nevada veins were called the Comstock Lode. It was a remarkable find; but the veins were so large that the mined-out tunnels were sometimes dozens of feet wide. They could no longer be shored up by the techniques of Agricola.

After a year, tunnels were caving in with such regularity that miners wouldn't stay on the job. Finally, trustees of one mine heard about a very bright young German-Jewish mining engineer, Philipp Deidesheimer, in California.

At nineteen, Deidesheimer had emigrated to join the California gold rush. He was now 28, and a highly respected mining expert. So he was called over to Virginia City.

But, after several weeks, Deidesheimer was no closer to a solution than anyone else. Tunnels kept caving in around the pine columns that shored up the brittle quartz substrate. Then, one night at a party, his host, a beekeeper, showed him his beehives.

Deidesheimer, his problem simmering on a backburner of his mind, suddenly saw those hives with a new set of eyes. Their cellular structure was remarkably strong and light. Why not, he thought, why not! He rushed from the party to his office. Three days later, he took a radically new structure down into the mines.

Do you remember building with Lincoln Logs when you were a kid? Well, that's how he made the bracing. He used a timber frame of interlocking cubical elements, four to six feet on a side. The excavation itself could wander wherever it wanted to. Deidesheimer simply filled it up with a beehive that was cubical instead of hexagonal. He called it the square set.

He didn't think to patent his timber square set. If he had, it might've made him rich. For had made the first leap forward in shoring up excavations since Agricola. It's the only structure described in detail in my Encyclopaedia Britannica article on mining.

Philipp Deidesheimer went on to other projects. When a new town sprouted up around his mining work in Montana, the citizens named the town Philipsburg, after him. He speculated, got rich several times, lost his shirt just as often, and he died poor in 1916.

But his finest legacy was that wonderful insight -- that leap-of-the-mind one summer's night in Nevada. Deidesheimer's greatest legacy was not a town -- not a fortune. It was a really good idea.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

R. Sagan, One Night of Brilliant Work. American Heritage of Invention and Technology, Summer 1987, p. 64.

G. Agricola, De Re Metallica (H.C. and L.H. Hoover, eds.). New York: Dover Publications Inc., 1950.

This episode is a greatly revised version of Episode 251.

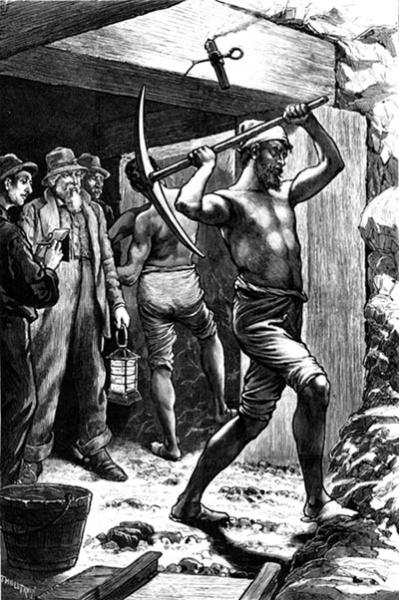

Typical timber square set bracing

as illustrated in a nineteenth-century magazine