Kurt Gödel

Today, a mathematician brings us down to earth. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

For some people Kurt Gödel was the greatest mathematician of the twentieth century. Well, I'm not crazy about superlatives, but Gödel was remarkable. He was born in 1906, part of a German enclave in Moravia, later to become part of Czechoslovakia.

His people were textile workers. He was shy, edgy, and so curious about everything that his family called him Herr Warum -- Mr. Why. He was already expert in languages, philosophy, and (especially) in math by the time he finished high school. He finished his doctoral dissertation in math while he was still 23.

His thesis was on an arcane subject: incompleteness. Gödel was on his way to showing the world something it didn't really care to hear. The body of his work eventually convinced us that, if we create any logical system with a complete set of axioms, those axioms cannot be consistent. And that's devastating. It means our best-laid system of logic will never give us the whole truth.

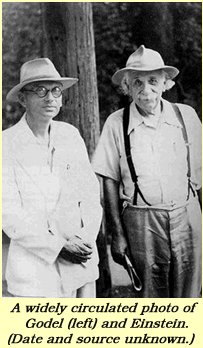

In any case, Gödel was still in his twenties when the Prince-ton Institute for Advanced Studies discovered him. He spent time there, on and off, during the 1930s. (He got to know Einstein.)

During this time, he was also on the faculty of the University of Vienna. His teaching there was awful. He lectured to the blackboard and attracted few students. He also spent time being institutionalized for recurrent severe depression.

Toward the late 1930s there was good news and bad new for Gödel. In 1938 he was married -- to a nightclub dancer. The bad news was that Hitler's noose was tightening. Gödel had run with Jewish intellectuals when he was in college. He was now about to lose his university post and be hauled off into the Wehrmacht.

So he and his new wife fled Austria. It was too dangerous to go west, so they took a train across Siberia and caught a ship from Yokohama to San Francisco. From then on, Gödel worked at Princeton. He and Einstein became close friends; but he was skeptical of Einstein's unified field theory and refused to work with him on it.

After he retired, his last two years were an awful downhill slide. First, his wife underwent major surgery; then he refused treatment for a severe prostate condition. Finally, he fell into deep depression and paranoia. Terrified that his food would be poisoned, he died of self-starvation.

Yet his work in philosophy and math repositioned our sense of self. Before Gödel, mathematicians thought they were standing at the door of absolute truth. Now it was clear that math, like science, was limited. After Gödel, we were both humbled and liberated. Our ambitions were carved back to human dimensions.

Gödel practiced a kind of Pangloss optimism. He looked for an afterlife. And one biographer, who knew him personally, quoted him as having said: "Our total reality and total existence are beautiful and meaningful." Perhaps that's why, despite his own dark journey, he left us all saner than we'd been before him.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

G. H. Moore, Gödel, Kurt Friedrich. Dictionary of Scientific Biography (C.C. Gilespie, ed.) New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1970-1980.

H. Wang, A Logical Journey: From Gödel to Philosophy. Cambridge MA: The MIT Press, 1996.

For more on Gödel, click here.

My thanks to Martin Golubitsky, UH Math Department, for his counsel.