Saturday Magazine

Today, an old magazine. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

I've been reading the 1836 volume of the British Saturday Magazine. This venerable periodical was, and it still is, provided by the Committee of General Literature and Education. They, in turn, were sponsored by the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge.

That sort of aegis can easily put us off our feed today. But this was a time when the Church of England owned the British intellectual establishment. In those days, only Anglican clergymen could teach at Oxford or Cambridge University. And the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge was pretty worldly in its outlook.

A typical edition of the Saturday Magazine began with an account of some exotic place — maybe Persia, India or China — maybe a byway in Spain or France. It took great interest in Australia — in Aborigines and their culture. The British presence in Australia had just taken root, and the British back home wanted to know about their strange land down under.

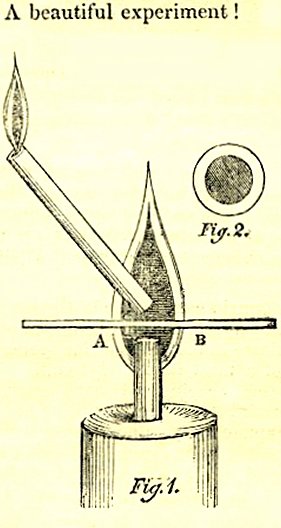

But I'm most drawn to a monthly feature: The Young Scientist. One series of these pieces is all about the chemistry of a burning candle. No author is named. But, from the style and content, it could well be spinoff of Michael Faraday's famous Lectures on the subtleties of candle flames.

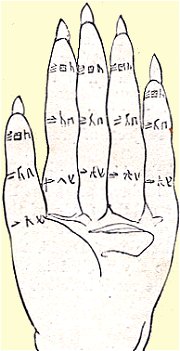

The technical content of all the science writings, is really quite good. One article is titled Mechanical Arithmetic. The first key-operated calculating machines lay fifteen years in the future, so it deals primarily with Greek and Roman forms of the abacus. It treats the Chinese abacus as a modern variation, and it goes on to tell how certain eastern Asians wrote numbers on the joints of their fingers to make their hands into a form of abacus.

The technical content of all the science writings, is really quite good. One article is titled Mechanical Arithmetic. The first key-operated calculating machines lay fifteen years in the future, so it deals primarily with Greek and Roman forms of the abacus. It treats the Chinese abacus as a modern variation, and it goes on to tell how certain eastern Asians wrote numbers on the joints of their fingers to make their hands into a form of abacus.

The article tells how the Court of the Exchequer got its name: The British financial offices once used a large table set up with a checker — or chess-board pattern on the top. It was called a saccaria and it functioned a lot like a big abacus. The operator used small coins as counters.

The magazine is also full of poetry. Wordsworth, Southey, Coleridge, and Washington Irving are all there. Most of the poems are Romantic paeans to wild nature, but sometimes with an edge. These lines by Wordsworth have an almost Ogden-Nashian twist:

The umbrageous oak, with arms outspread,

Full oft when storms the welkin rend,

Draws lightning down upon the head

It promised to defend.

So the riches pour forth: tricks of geometry and arithmetic, explanations of medicinal and toxic features of purple Foxglove — anatomy, stories, technology, and folkways.

If I were a bright twelve-year-old British kid in that world without movies or radio, I can well imagine hanging around the bookstall, waiting for this week's installment to arrive — this week's cornucopia of mind-stretching adventure.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Saturday Magazine, Volume the Eighth, January to June MDCCCXXXVI, London: John William Parker.

My thanks to Catherine Patterson, UH History Department, for her counsel on this episode.