Multiple Authors

Today, whose work is this? The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

In 1935 a superb group of nine mathematicians banded together under the fictitious name of Nicolas Bourbaki, and they set out to write the foundations of all mathematics, based on set theory. They produced more than thirty volumes of extremely rigorous mathematics. In the near term they were quite influential. In the long term they proved a bit more austere than useful. Yet Bourbaki remains a major feature in the landscape of mathematics.

What makes this so interesting is the very idea of a group of top mathematicians giving themselves over to anonymity. Their resumes reflected only that they were members of Bourbaki.

Multiple authorship was rare before the twentieth century. And, as it's become common, it has not followed the Bourbaki model. Instead, it reflects the need for recognition, as well as a belief that contributions should be reflected accurately. Today, the nearest we get to the Bourbaki model is in certain company reports — which differ profoundly when they list no authors at all.

Now Donald Kennedy, editor of Science magazine, has written an editorial titled Multiple Authors, Multiple Problems. And well he might. I've just checked out the last two issues of Science, and counted an average of five authors for each of the major papers.

Kennedy suggests that the US Government has had a big influence by promoting team science. That, in itself, might be good, he allows. But, oh, the problems! And they all revolve around matters of responsibility. Who do you go to if you have a question about something in a paper? Who takes the fall if data turn out to be fudged? Who gets the Nobel Prize for the work?

I've seen promotion and tenure committees mired in questions about what the order, and the number, of authors means. If authorship is alphabetical, does that mean the ten authors can claim only ten percent of the credit each? By the way, that number ten is not unheard of. I've seen papers with over a hundred authors.

I'm old enough to remember a time when anyone with a name on a paper was assumed to be responsible for answering any question about that paper. Now Kennedy talks about the possibility of allowing each author to define his or her role in the work. But, he adds, "[We have] no plans to pass out ... our annual award for the best Science paper, in little bits and pieces."

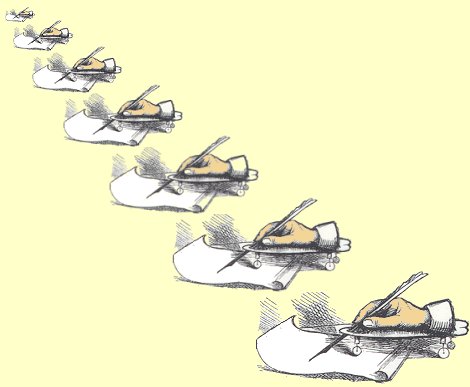

I was talking this over with a colleague when I was surprised to hear myself saying, "Two things I know for certain: One is that writing a book or a paper is not a lonely and solitary act. The other is that it is a lonely and solitary act."

One might find cases where two peoples' vision and comprehension truly melded in one written work. But three people? Or twelve? Not likely. I don't suppose we'll ever know just what really went on within the group called Bourbaki — any more than we'll ever trace Melville's mind all the way through to Moby Dick.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

D. Kennedy, Multiple Authors, Multiple Problems. Science, Vol. 301, 8 August, 2003, pg. 733.

I am grateful to Lewis T. Wheeler, Editor in Chief of the journal Mathematics and Mechanics of Solids, for additional counsel.