The Christmas Lectures

Today, the Christmas Lectures. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

A marvelous and wonderfully appropriate Christmas tradition in London is a set of public lectures given by the Royal Institution of London. These so-called Christmas Lectures on science run during the Holiday season, and they're meant for young people.

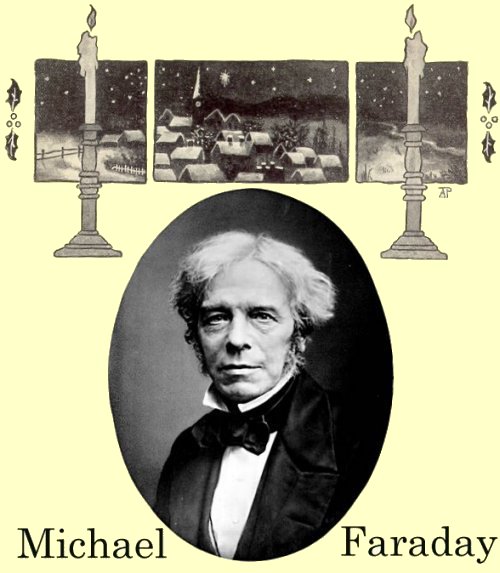

This gift of the Royal Institution to children is now a venerable Christmas observance in which science is placed within the grasp of the next generation. The lectures trace back, interrupted only by the years of the WW-II London Blitz, to when they were begun by a still-young Michael Faraday.

The first set of Christmas Lectures was given by Faraday's close friend J. Wallis. But, during the next thirty-five years, Faraday presented nineteen of the sets of lectures. And they've born the stamp of Faraday's remarkable mind ever since.

That's as it should be. For gentle Michael Faraday had uncanny scientific insight. He was remarkably able to cut to the bone and tell children just what would best reveal the things science had to show them. He also had an unmistakable sense of theatre. One stunt would be, without warning, to suddenly start flinging large metal objects across the room at a giant electromagnet -- fire tongs, then a poker. And there they would adhere.

But Faraday was no mere showman. It was he who set the foundations of modern electrical theory. His first lectures bore the stiff title: Course of Six Elementary Lectures on Chemistry, adapted to a Juvenile Auditory. His later set of lectures on the chemical history of a candle has become a classic of both scientific and children's literature.

Between 1851 and '61, Faraday gave all the Christmas lectures. But, at the last, he was seventy years old and falling victim to what was probably Alzheimer's disease. He died six years later.

The year after his death, Faraday's friend John Tyndall wrote his biography. Tyndall was 29 years younger and regarded Faraday with near holy admiration. The deeply religious Faraday had begun the series; now the agnostic Tyndall became its primary heritor.

Tyndall gave the next Christmas Lectures after Faraday, and he did so a total of eleven more times thereafter. Like Faraday's, his lectures became classics. He began his Lessons in Electricity, the 1876 lectures, with these words,

Many centuries before Christ, it had been observed that yellow amber [called elektron], when rubbed, possesses the power of attracting light bodies.

And, in one stroke, he paid homage to Faraday's religious beliefs while he awakened students with a lovely linguistic connection.

Thus, for nearly two centuries, the Royal Society has sustained this very special gift to the young -- the handling of mystery and the celebration of wonder -- making flesh and blood of ideas that once seemed to hover beyond the reach of understanding.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

J. Tyndall, Faraday as a Discoverer. London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1868.

J. Tyndall, Lessons in Electricity at the Royal Institution 1875-6, New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1877.

L. Pearce Williams, Michael Faraday. New York: Basic Books, Inc. 1965.

See also the many references to The Christmas Lectures to be found the Internet.