The Hidden Wright Brothers

Today, we gradually learn about the Wright Brothers' flight. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

An article in the 1904 Puck magazine poked fun at attempts to build flying machines. It said that inventors would get airplanes into the sky just as soon as the law of gravity was repealed. The problem was, that article came out the year after the Wright Brothers had already flown.

That becomes even more puzzling when historian Roger Bilstein writes about our utter confidence in the inevitability of airplanes at the turn of the century. Dirigibles had been around since 1852. Thousands of human-carrying balloons had flown since the eighteenth century. Lilienthal's and Chanute's successful glider experiments were well known. It could only be a matter of time.

One of the strongest public voices for the inevitability of the airplane was Samuel Pierpoint Langley, secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. Working with government funding, Langley had flown a successful steam-powered model airplane in 1896. Then, in the fall of 1903, only months before the Wrights' successes at Kitty Hawk, Langley made two attempts to launch his huge airplane, the Aerodrome, from a large houseboat on the Potomac River.

The press and photographers covered both tries. Each time, the Aerodrome crashed into the river on takeoff. The reaction was, of course, ridicule. The Washington Post called Smithsonian staff "stuffers of birds and rabbits." The Boston Herald said Langley's efforts would better be directed toward developing submarines.

That Puck article, it turns out, had focused on Langley without ever having heard of the Wright Brothers' repeated flights in the isolated sand dunes of the Atlantic coast. Not until 1905 was an eyewitness account of their flight finally published in, of all places, a magazine entitled Advances in Bee Culture.

I asked my father, born ten years before the Wrights flew, what he'd thought when he'd first heard about them. His answer was a surprise. As a schoolboy, he'd been aware only of vague rumors. Somehow, the word didn't get out. All the while, poor old Langley served as a lightning rod for ridicule. Small wonder that he died only three years after Kitty Hawk.

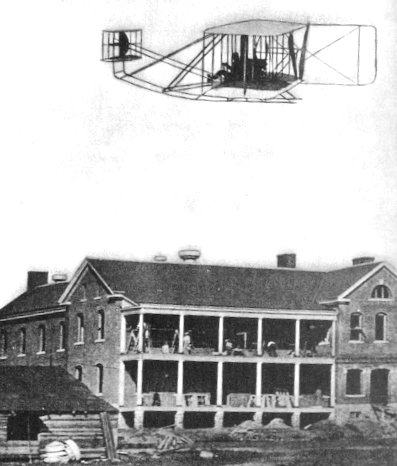

When Santos Dumont made the first European flight in 1906, the Wright Brothers were routinely making flights over Huffman Prairie near Dayton. The next American to fly was Glenn Curtiss, in 1908. But, by then, the military had wind of the Wrights' achievement, and the U.S. War Department concluded a $25,000 deal with the Wrights. The Army received its first airplane in 1909.

Only then did airplanes go public. Only then did flying machines become a mania. And we're left with a startling time lag. Perhaps flight had been anticipated too long. Perhaps the idea that it'd actually come to pass was too bizarre. In any case, it is remarkable that anything so long-awaited actually existed for five years before we really knew it was there.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Bilstein, R. E., Flight in America: From the Wrights to the Astronauts. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1984, Ch. 1.

A Wright Flyer over Fort Myer, VA.

(The Outing Magazine, May, 1909.)