Zeppelins

Today, we ride in an airship. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Powered air transport took two very different forms: heavier-than-air flight and lighter-than-air flight. Heavier-than-air flight has developed steadily, but lighter-than-air transport seems for the moment to have come and gone. The grand hotels that buoyed gently through the skies in the early 20th century have completely vanished. Little more than advertising blimps survive.

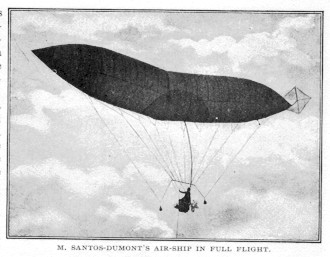

The first successful powered balloon flight was made by the French steam-engine designer Giffard in 1852. He mounted a three-horsepower steam engine of his own design on a 147-foot-long balloon and chuffed away at six miles per hour on a three-hour ride over the suburbs of Paris.

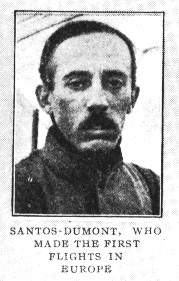

Many powered balloon flights were made during the next half century, and in 1900 Henry Deutsch, a French financier, offered a 100,000-franc prize to the first person who could fly the 14-mile course from the Paris Aero Club around the Eiffel Tower and back in 30 minutes. The two leading contenders were the young Brazilian Santos Dumont and the German Count von Zeppelin.

Santos Dumont just barely won the prize in 1901, but he soon lost hope for lighter-than-air flight. "To propel a dirigible balloon through the air," he complained, "is like trying to push a candle through a brick wall." He turned to heavier-than-air flight and in 1906 was the first European to fly an airplane.

But Count von Zeppelin went on to develop the rigid dirigible into a glorious machine. He was flying passengers by 1910 and achieving remarkable popularity in Germany. In its enthusiasm, the public completely forgave Zeppelin's spectacular failures. His dirigibles weren't too effective as warships in WW-I, but after the war he began transoceanic service with really grand airships.

The grandest of these was the Hindenburg. Completed in 1936, it was just a little shorter than the Queen Mary. It served 50 passengers and crossed the Atlantic in 2½ days. This two-story flying hotel had staterooms, a lounge, a promenade, a dining room that offered venison and roast gosling -- all the amenities anyone might wish.

When the Hindenburg caught fire and burned in Lakehurst, New Jersey, in 1937, that put an end to the great dirigibles. Santos Dumont, it seemed, had made the right choice. Rather than tackle the problems of making hydrogen-filled balloons safe, people abandoned them and went with the airplane.

But who -- crammed like a sardine on a transatlantic jet and suffering jet lag -- doesn't look back at the gentle elegance of these quiet monsters and wonder about the complex factors that influenced this particular decision.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Archbold, R., and Marschall, K., The Hindenburg: An Illustrated History. Toronto, Ontario: Madison Press Books, 1994.

This episode has been revised and updated as Episode 1335.

From The Modern Aeronaut, 1901

From the 1910 Cosmopolitan Magazine

From the 1911 Encyclopaedia Britannica