Wright and Langley

Today, an attempt to rewrite history. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

The close of the nineteenth century found both Samuel Pierpont Langley and the Wright Brothers, Orville and Wilbur, working hard and systematically to create powered controllable flight. Langley had government support and enormous public exposure. The Wright Brothers worked quietly using their own resources.

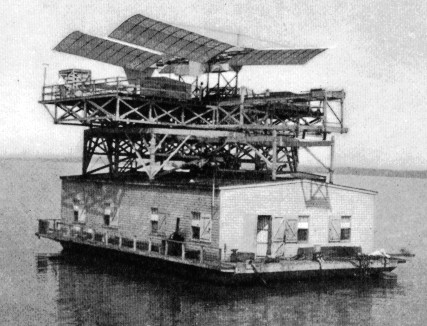

Langley tried to fly on October 7, 1903. His huge 54-foot-long flying machine had two 48-foot wings -- one in front and one in back. He launched it from a catapult on the Potomac River. While the cameras turned, it fell like a sack of cement into the water. On December 8th he tried again. This time the rear wing caved in before it got off its catapult. Only nine days after Langley's second failure, the Wright Brothers flew a trim little biplane (with almost no fanfare) at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina.

They succeeded because they'd mastered the problem of controlling the motion of an airplane in flight. They'd done four years of careful experimentation with kites and gliders beforehand.

But governments make interesting bedfellows. Charles Walcott, a longtime friend of Langley's, had been influential in funding Langley's work. Walcott became director of the Smithsonian Institution in 1906, the same year Langley died. He immediately set up a Langley medal, a Langley Aero Lab, and a Langley memorial. In 1914 he hired Glenn Curtiss to rebuild the Langley Aerodrome and show that it really could fly. Since Curtiss was tangled in bitter patent disputes with the Wrights, that made a poor recipe for objectivity.

Curtiss went to work strengthening the structure, adding controls, reshaping Langley's plane aerodynamically, and relocating the center of gravity. In short, he made it airworthy. He flew it for 150 feet in 1914. Then he went back and replaced the old motor as well. On the basis of Curtiss's work, the Smithsonian honored Langley for having built the first successful flying machine.

It was 1925 before Orville Wright roused American sentiment to his cause. What he did was to place the original airplane -- this American treasure -- in London's Science Museum. Finally, in 1942, the Secretary of the Smithsonian, Charles Abbot, authorized publication of an article that clearly showed how the reconstruction of Langley's Aerodrome had been rigged.

With that, Orville told the British that his airplane should be returned to the Smithsonian Institution after the war. Eleven months after Orville died in 1948, the famous Wright airplane came back to America -- back to the Smithsonian, which had once been such solid Langley turf. Today the best known biplane that ever flew hangs over a label giving the Wright Brothers their due.

Today a NASA center, an Army air base, and the CIA headquarters are all named after Langley. But that's all right. If Langley didn't win the race, he was there at the finish line. And Walcott's attempt to rewrite history hasn't made any of us forget Kitty Hawk.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Crouch, T. D., The Feud Between the Wright Brothers and the Smithsonian. American Heritage of Invention & Technology, Spring 1987, pp. 34-46.

This episode is a revised version of Episode 32.

Langley's Aerodrome aboard its houseboat launching platform

From The Art of Flying, 1911