John Fitch

Today, America's first steamboat. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

John Fitch was born in 1743 in Connecticut. His mother died when he was four; his father was harsh and rigid. A sense of injustice and failure wreathed his life from the start. Pulled from school when he was eight and made to work on the hated family farm, he became, in his own words, "almost crazy after learning."

He fled the farm and took up silversmithing. He married in 1776 a wife who reacted to his manic-depressive extremes by raging at him. He finally ran off to the Ohio River basin, spent time as a prisoner of the British and the Indians, then came back to Pennsylvania in 1782, afire with a new obsession. He meant to make a steam-powered boat to navigate those western rivers. In 1785 and 1786 Fitch, and competing builder James Rumsey, looked for money to build steamboats. The methodical Rumsey gained the support of George Washington and our new government. Fitch found private support, then rapidly built an engine with features of both Watt's and Newcomen's steam engines. He moved from mistake to mistake until he'd made our first steamboat, well before Rumsey.

It was an odd machine -- driven by a rack of Indian-canoe paddles. Yet, by the summer of 1790, Fitch used it in a successful passenger line between Philadelphia and Trenton. He logged thousands of miles at six to eight mph carrying passengers that summer. But it failed commercially. People wouldn't take it seriously. All they saw was a curiosity -- a stunt. And Fitch, with of his personality extremes, couldn't sustain financial backing.

Failure broke Fitch. He retired to Bardstown, Kentucky, and struck a deal with the local innkeeper. For 150 acres of land, the man agreed to put him up and give him a pint of whiskey every day while he drank himself to death. When that failed, Fitch put up another 150 acres to raise the dose to two pints a day. When that failed, Fitch finally gathered enough opium pills to kill himself.

They'd called him "Crazy Fitch," and now they buried him under a footpath in the central square. In 1910, the Daughters of the American Revolution finally put a marker over the spot. It identified him only as a veteran of the American Revolutionary War.

And I'm left haunted by the picture of this six-foot-two figure in a beaver-skin hat and a black frock coat -- stumbling the streets of Bardstown, the butt of children's jokes -- unable to see that his dream had not failed. History honors Fitch far better than he honored himself, for it was he who set the stage for Robert Fulton. He made it clear that powered boats were feasible.

To function creatively we have to function at risk. Watt and Fulton took risks and won big, but not before they'd suffered failure. The trick, of course, is to lose one day and come back to win the next. But that's possible only when we're able to feast upon the pure pleasure of our God-given creative processes.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Flexner, J. T., Steamboats Come True. 2nd ed. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1978.

Harris, C. M., The Improbable Success of John Fitch. American Inventions: A Chronicle of Achievements that Changed the World, New York, Barnes & Noble Books, 1995, pp. 11-17.

This is a revised version of Episode 14.

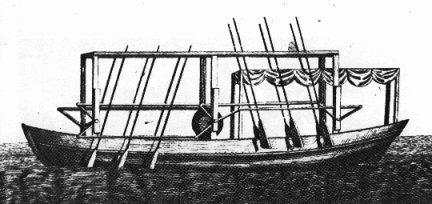

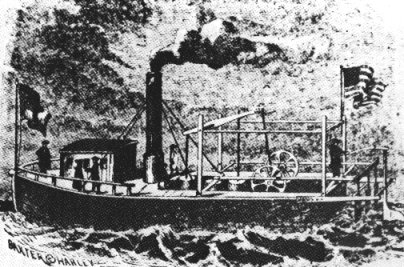

John Fitch: 1743-1798

From Lloyd's Steamboat Directory, 1856

Fitch's first steamboat, driven by Indian canoe-type paddles.

From the Columbian Magazine, 1786

Fitch's successful steamboat from 1790

From Westcott's Life of Fitch, 1857