An Engineer Named Calder

Today, an engineer takes up sculpture. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Alexander Calder's joyous orange Crab marks our Houston Museum of Fine Art. You know you're there when you see it. Calder created wonderful abstract structures -- mobiles of balanced steel plates, his so-called stabiles sitting solidly on the ground. I especially like the way he evokes animals with segmented slabs of steel. That menacing Crab lurking by our museum entrance is a stabile. Whether or not know you Calder's work, you've certainly seen countless imitations of the style he created. He is one of the great modern artists whose work has settled into the background imagery of everyday life.

Calder was born in 1898, and art historian Joan Marter tells about the artistic silver spoon in his mouth. Calder's father and grandfather were both noted sculptors. His father oversaw sculpture for the San Francisco Panama-Pacific Exposition in 1915 . When it was clear that Calder had a talent for mechanics, his parents built a workshop for him. The boy grew up making things in his basement and hanging out in his father's studio.

After high school in San Francisco, he chose to study mechanical engineering at Stevens Institute of Technology. His parents were pleased. They didn't want him taking up art. When he graduated in 1919, it soon became clear that he didn't want to work in an engineering company. But the education stuck to him -- kinematics, materials, manufacturing processes.

Calder worked at this and that for a while. Then an epiphany changed his life while he was serving as a fireman on a passenger ship. He lay upon a coil of rope at dawn one day as the sun came up, fiery red, with the moon showing silver against the last of the night sky. "It left me with a lasting sensation of the solar system," he wrote. And he went off to art school in New York.

Calder committed himself to sculpture, but the engineer in Calder had simply found its focus. His mobiles are studies of balance and kinetics. Every piece is an exercise in materials science. His stabiles are sophisticated steel construction. Down through the 1930s he honed his skills and forged his artistic maturity. Calder's works became everything good design must be: economical, durable, and superbly evocative. And he wrote:

How does art come into being? Out of volumes, motion, space carved out within the surrounding space ... Out of vectors ... motion, velocity, acceleration, ... momentum ... Thus [the elements of art] reveal not only isolated moments, but a physical law [relating] the elements of life.

So Calder returned to engineering through art just as T.S. Eliot arrived where he'd started out in his poem, Four Quartettes. Eliot wrote,

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Marter, J. M., The Engineer Behind Calder's Art. Mechanical Engineering, December 1998, pp. 52-57.

Eliot, T. S., Four Quartets. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1943.

For more on Calder, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexander_Calder

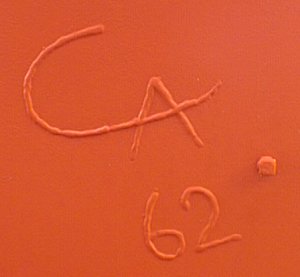

Calder's Crab (above) and his signature on the Crab (below)

Photos by John Lienhard