here do we find these ghost-laden books? They occupy a region just below our normal book radar. High-end rare book dealers sometimes acquire them along with more elegant materials when collections come on the market. They'll put them off in a corner for sale, or they'll remainder them to low-end used bookstores. Those low-end stores are the ones that I haunt.

here do we find these ghost-laden books? They occupy a region just below our normal book radar. High-end rare book dealers sometimes acquire them along with more elegant materials when collections come on the market. They'll put them off in a corner for sale, or they'll remainder them to low-end used bookstores. Those low-end stores are the ones that I haunt.

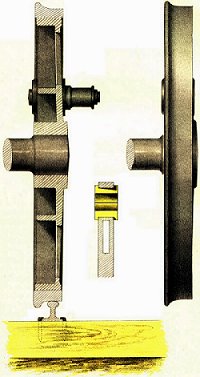

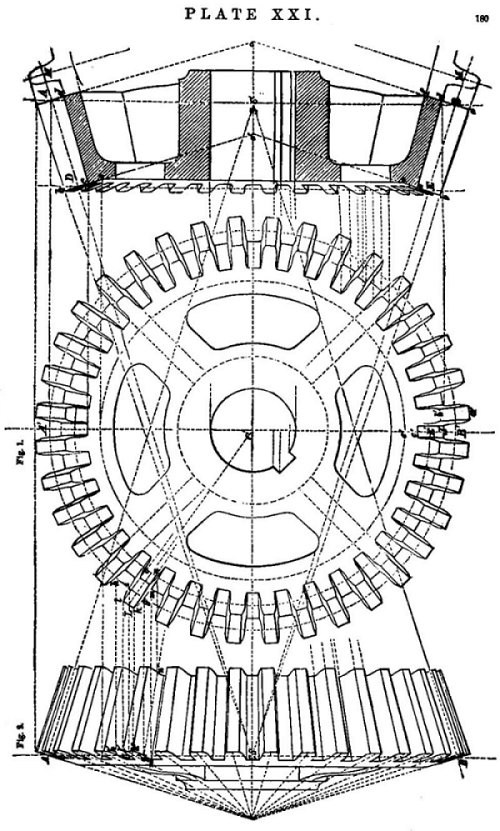

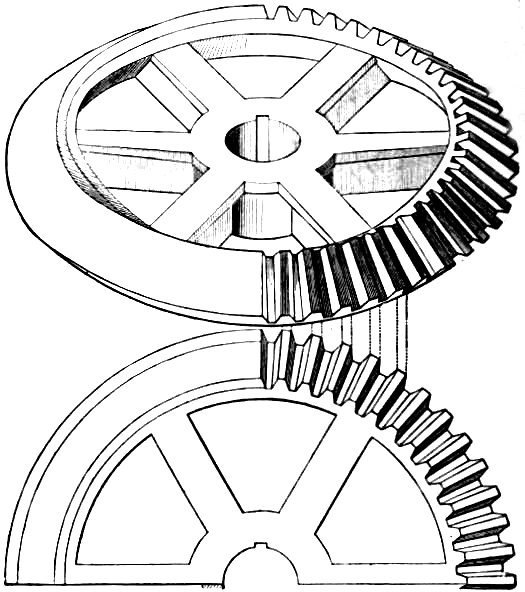

Another place to find them is off in the stacks of large libraries. Take this 1866 edition of a drafting text that first came out in 1857. It turned up in a forgotten corner of our university library and I was stunned when I opened it. It's filled with crisp images of architecture, machinery, perspective exercises, and topography. Colored plates have been added, or tipped in, as book people say. These chromolithograph images could not be made part of the black and white pages that were printed 24-or-so on a sheet, then folded and sewn together into so called signatures. So they've been tipped in between the signatures. As a result, this pre-Civil War window upon America truly does blur the line that vainly attempts to separate art from engineering.

The son of one Milton G. Howe gave this book to our library. Howe, an early Texan, had studied civil engineering at Dartmouth and he'd worked on railways in Illinois. But then war began. Like Brandon, he joined a Confederate regiment. But now it's 1866, and the War is over. So he signs his new edition of the book with an ill-cut quill pen. Not only does he sign in front, he also signs his name across random pages inside. His ink, alas, spreads and partly obscures his name.

The son of one Milton G. Howe gave this book to our library. Howe, an early Texan, had studied civil engineering at Dartmouth and he'd worked on railways in Illinois. But then war began. Like Brandon, he joined a Confederate regiment. But now it's 1866, and the War is over. So he signs his new edition of the book with an ill-cut quill pen. Not only does he sign in front, he also signs his name across random pages inside. His ink, alas, spreads and partly obscures his name.

Howe was quite successful. He became chief engineer of the Texas Central Railroad, then its general superintendent. And, when the time came, this Confederate veteran sent his son off to Phillips Academy and MIT, back in Yankee Massachusetts. His son, who also went by the name Milton, worked his whole life as a civil engineer – first on rail, then on roads and hydraulic structures.

And Howe's father-in-law, Andrew Briscoe, was a rail pioneer as well. Briscoe was a lawyer who became Chief Justice of my own Harris County, then turned to developing our embryonic Texas rail system. Like Howe, Briscoe had also done his time in war – more successfully than Howe. He was one of Sam Houston's commanders at the Battle of San Jacinto, where Santa Ana was defeated and Texas briefly became a sovereign nation.

And Howe's father-in-law, Andrew Briscoe, was a rail pioneer as well. Briscoe was a lawyer who became Chief Justice of my own Harris County, then turned to developing our embryonic Texas rail system. Like Howe, Briscoe had also done his time in war – more successfully than Howe. He was one of Sam Houston's commanders at the Battle of San Jacinto, where Santa Ana was defeated and Texas briefly became a sovereign nation.

Still, these lives were about the technologies that defined us, not about the wars that got in our way. And images in this old book reveal the texture of those times. Huge bevel gears and air pumps, Victorian houses, complex machinery displayed in even more complex projections, a lovingly shaded view of a heavy lag screw alongside a pastoral view of a country bungalow. And, in the back, a chromolithograph page uses a railway wheel to illustrate how to do a color drawing.

You and I use computers to create images such as these today; and, when we do, something changes. The human mind no longer has to stretch quite the way it did to produce the pictures in Milton Howe's lovely old book. The complexity that we see on its paper was first conquered in the human mind.

That mental capacity – that ability to visualize – is what the book sought to develop. It was exactly the ability that equipped people in Howe's day to build America so rapidly and to build it so well. In this old book we find a surprisingly intimate view of 19th-century engineering. It is intimate because the ghosts who inhabit this book reveal the way in which mind, image, and artifact were once quite inseparable.

Representing a bevel gear accurately is quite a feat. Doing so in perspective is fiendishly complex.

Appletons' Cyclop�dia of Drawing, Designed as a Text-Book for the Mechanic, Architect, Engineer, and Surveyor, Comprising Geometrical Projection, Mechanical, Architectural and Topographical Drawing, Perspective and Isometry. (W. E. Worten, ed.) (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1866). This is Milton Grosvenor Howe's copy. The first printing was done in 1857.

Howe's son, J. Milton Howe (1874-?) had a distinguished career as a Civil Engineer. He is listed in a number of 20th-century biographical sources. Barbara Kemp, UH Library, located genealogical records of Milton G. Howe (1834-1902), Andrew and Mary Briscoe (1810-1849, 1819-1902) and others of this distinguished family. There is a fairly substantial record of Andrew Briscoe, for his role in Texas history. He was one of the signers of the Texas Declaration of Independence.