n this particular afternoon, I cut open a box that's just arrived. I shake out the polystyrene popcorn, and removed a wrapped package from Seattle. There it is: a perfectly lovely copy of A Treatise on Mechanics, from 1832. This is one of the Reverend Dionysius Lardner's Cabinet of Natural Philosophy books. Lardner co-opted all kinds of noted writers into working on a vast series of books – first technical, then literary. Mary Shelley wrote anonymous copy for Lardner after she'd written Frankenstein. This particular book was written by one Captain Henry Kater. As for the ghost, we'll meet him in a moment.

n this particular afternoon, I cut open a box that's just arrived. I shake out the polystyrene popcorn, and removed a wrapped package from Seattle. There it is: a perfectly lovely copy of A Treatise on Mechanics, from 1832. This is one of the Reverend Dionysius Lardner's Cabinet of Natural Philosophy books. Lardner co-opted all kinds of noted writers into working on a vast series of books – first technical, then literary. Mary Shelley wrote anonymous copy for Lardner after she'd written Frankenstein. This particular book was written by one Captain Henry Kater. As for the ghost, we'll meet him in a moment.

The book itself is one more cheap technical textbook and it provides a particularly strong picture of the subtle interweaving of technology with the seeds of social change. It came out early enough to have been produced in much the same way as Mary Ann Howley's natural philosophy text was. But, unlike hers, this book's signatures have all been cut, and throughout it, pencil marks make it clear that the owner had digested it carefully.

As we turn pages, we read about matter, and about the forces that act upon matter. The book explains pulleys, gears, engines, and screws. Kater's frontispiece includes an image of four forms of levers – cantilever beam, wedge, lag screw, and simple lever – all being put to use by three cherub-like children. It's a whimsical way to signal the mechanical advantage these mechanical elements provide.

But there's more going on here: Kater is also spinning a philosophy around the new atomic theory of matter and his words obviously resonate with the book's young owner. He's a 22-year-old student at the University of Pennsylvania named Richard Newton, and he's marked this startling sentence in the book:

Although we are unable by direct observation to prove the existence of constituent material atoms of determinate figure, yet there are many observable phenomena which render their existence in the highest degree probable, if not morally certain.

Morally certain? Hardly the way anyone would talk about atoms today. And yet Kater was no rambling generalist. He'd started out as a creature of the old empire. He'd studied some law – some mathematics; and then he'd purchased a commission with the British Army in India where he worked on land surveys. Back in England he taught at Sandhurst – Great Britain's West Point. He did distinguished work in clock design, weights and measures, and many other areas of instrumentation. For those accomplishments he was made a member of the Royal Society.

Kater was a creature of the 18th century, looking upon the wonder of 19th-century atoms with the awe of an outsider. He published this book in 1832, when he was 55. That was two years before Richard Newton signed it, and three years before his own death.

Let us meet this Richard Newton who entered a world where atoms would no more have to be justified by moral certainty than Isaac Newton's law of gravity would. History hasn't forgotten Richard Newton. He was born in England in 1812 and his family moved to America when he was 12. He received some manual training, but then went to college at the University of Pennsylvania. He graduated and went on to become an Episcopal clergyman who wrote voluminously. His 18 volumes of published sermons for children were translated into a score of languages. He was a low-church evangelical who helped hold the church together when other low-churchmen tried to divide it. And he was a potent opponent of slavery.

In that we pick up echoes of an earlier Newton – no relation, but a kindred spirit: John Newton was born in 1725, went to sea at 11, and was captain of a slave ship by the age of 23. When his ship almost sank during a terrible thunderstorm, he underwent a religious conversion and repudiated the slave trade. John Newton wrote many familiar hymn texts, but none better known than Amazing Grace. Like Richard Newton after him, he too became an Anglican clergyman and a formidable enemy of the British slave trade.

Richard Newton displayed an intensity to match that of John Newton, but he was a reconciler before he was a warrior. And that's why I have to catch my breath when I spot a bit of marginalia in this old mechanics text. Under his name, he's penciled four lines of verse.

Full many a shaft at random sent

Finds mark the archer little meant

And many a word at random spoken

May soothe or wound the heart that's broken.

The first two lines were common currency in his time. Where the last two come from, I do not know. Whether or not he made them up, or borrowed them, they are certainly emblematic of the life that he led after he left school. Before Newton studied theology, he studied mechanics, underlining passages about the moral force of the new atomic science and doing lever and beam-loading calculations on the flyleaves. Then he turned his attention to healing the many wounds of a world undergoing radical change.

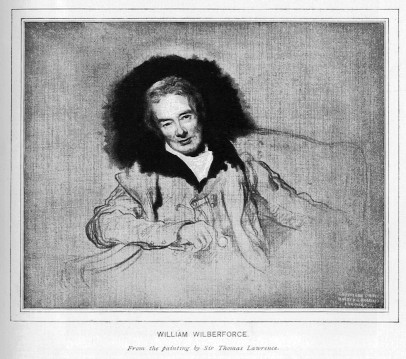

Richard Newton also named one of his sons William Wilberforce Newton, after the British member of the House of Commons who had been instrumental in stopping England's slave trade. This is a ghost whom I suspect is at peace with himself, even if his work might seem as unfinished as ever in our world today.

H. Kater, and D. Lardner, A Treatise on Mechanics. (Philadelphia: Carey & Lea, 1832).

See the Dictionary of American Biography for information on Richard Newton.

Richard Newton gave the name of William Wilberforce to one of his sons. William Wilberforce was the prime mover of the British antislavery movement.