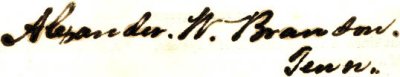

friend recently gave me a copy of another Davies textbook. It was an 1835 edition of his Elements of Surveying, first published in 1830. I'm delighted to have this early edition, because I have a much later one for comparison. And both books are inscribed. The 1835 one is signed in ink by an Alexander W. Brandon.

friend recently gave me a copy of another Davies textbook. It was an 1835 edition of his Elements of Surveying, first published in 1830. I'm delighted to have this early edition, because I have a much later one for comparison. And both books are inscribed. The 1835 one is signed in ink by an Alexander W. Brandon.

But beyond the signature, we find a curiously disturbing item written in pencil on the front flyleaf in the same handwriting. It says,

If man has a natural desire to do evil but, by grace overcomes that desire is he guilty before God? NO

If that doesn't whet our curiosity about Alexander Brandon, I don't know what would. So we go looking and find a 1902 obituary. He was born three years after the book was published and he was not its first owner. In fact another flyleaf has been torn out. Brandon probably removed a previous owner's name.

Brandon was raised in Columbia, Tennessee, and was 23 when the Civil War began. He opposed Secession, but loyalty to Tennessee trumped his beliefs. He went off to war with his three brothers to fight for the Confederacy.

His regiment saw the worst of the slaughter. He started at the Battle of Shiloh and his hand was seriously wounded at Perrysville. He continued as a cook, and as a nurse to a huge number of wounded. The regiment suffered terrible losses. When it finally surrendered at Greensboro, only a third of its men remained.

A former messmate writes in praise of Brandon, adding that, "As a nurse he was tender and careful as a woman." He tells us that, once back in Tennessee, Brandon worked as a carpenter and as a contractor.

A former messmate writes in praise of Brandon, adding that, "As a nurse he was tender and careful as a woman." He tells us that, once back in Tennessee, Brandon worked as a carpenter and as a contractor.

So he no doubt made good use of this old book, filled as it is with geometry and means for measuring Earth's three-dimensional surface. Yet that strange, possibly guilt-ridden, inscription hovers like ectoplasm. What was it like to be taken out of the line of fire early in war, then spend years watching your comrades torn to bits? What was it like to go on to a productive life – to marry, raise children and live to a ripe age with such memories?

That was the older edition of Davies' book. My later edition was inscribed by my mother to my father. He'd just taken up a second career in surveying. My father had also gone to war. As a WW-I pilot in France, he didn't see action before the Armistice. He spent the rest of his life cursing himself for failing to have wangled his way into combat.

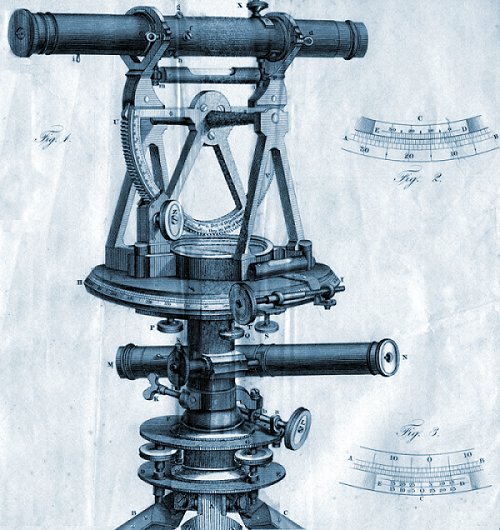

The book includes a fine drawing of a surveyor's transit – just like the one used by George Washington, Alex Brandon, and my father. Even I used that transit, working with returning WW-II veterans as we surveyed within the brush of Oregon and Washington. That's why I see something beyond pallid Victorian sentiment in the obituary's conclusion: "Returning to the vocations of peace, Mr. Brandon met and discharged his duties as a citizen with the same fidelity that characterized him as a soldier."

Brandon leaves us with a pointed reminder of just how puzzling and indistinct the voices of ghosts can be. Yet I find them all the more powerful just because of their muted ambiguity.

C. Davies, Elements of Surveying and Navigation. 5th ed., (Philadelphia: A. S. Barnes, and Co., 1835). (The first edition came out in 1830.)

C. Davies, Elements of Surveying and Navigation. Revised Edition (New York: A. S. Barnes & Burr, 1865)

Alexander Winburn Brandon's obituary and photo may be found in Vol. 10 of the Confederate Veteran, 1902, pg. 565-566. Above the photo is written, "After life's fitful fever he sleeps well."

Brandon's messmate A. S. Horsley writes further about him in Vol. 11 of the Confederate Veteran, 1903, pp. 560-561.

My thanks to Herman Detering, Detering Book Gallery, for the 1835 edition.