Reflections On Corporate Singing

for the Chorus America Conference, Doubletree Hotel at Allen Center,

400 Dallas at Bagby, 9:30 AM, Saturday, June 6, 1998

by John H. Lienhard

Mechanical Engineering Department

University of Houston

Houston, TX 77204-4792

jhl [at] uh.edu (jhl[at]uh[dot]edu)

Seven years ago I had one of those defining experiences. Or maybe I should call it an interpretive experience. My wife and I had gone to hear the University of Chicago Motet Choir. We listened as forty apple-cheeked, bespectacled young students ran a gamut of fine music. We heard forty serious, and slightly nerdish, students, full of the wonder of Hans Leo Hassler and Jacob Handl. We heard forty budding mathematicians, philosophers, poets, and chemists.

It was an eerie experience for me. For there I had stood, forty years earlier. The same music shaded my whole learning of thermodynamics and beam theory. It ran in my mind and tempered my life when I, too, was infinitely young.

They sang a Byrd mass — the same Byrd mass I had played in my head all through basic training. The army had taken me away from the university. For two years, while I'd stood in line, marched, washed dishes and waited, I'd played that mass through in my head and let it sustain me.

My wife nudged me as we listened. "Look," she whispered, "they feel as though they're the first people who've discovered all that music." She should know. She and I met, long ago, in a group singing Vaughan Williams, Poulenc, and Purcell.

The performance on stage was clean and in tune. I suppose it lacked somewhat in passion. But that's because youth itself lacks passion. Passion is still hypothetical. Those singers had so much to learn. The Latin mass was still an antiquarian exercise. What's the meaning of Dona nobis pacem when you've yet to suffer strife?

Toward the end they did a piece by the fine German choral composer Hugo Distler. Distler wrote during Hitler's rise. He was anti-Nazi, and he suffered for it. He committed suicide when he was only 34. He'd expected to be drafted, and he couldn't bear the idea. Not even his music could sustain him in a Nazi army.

Now that's drama those 20-year-olds could fathom. With Distler, the singing took on a new dimension. And so I watched process taking place, the same process that'd shaped me. I realized I was seeing much more than just a concert. I was seeing music molding the lives of forty smart young people. Music was serving as a window into the world and a window into history. It was holding up a mirror of themselves.

A few days later they were all back to their paper chase. But the medium of music was now revealing things about physics and literary criticism that they never would've seen otherwise. How do I know that? I know because I have walked precisely that same road. That was an important night for me. It helped show me who I am by reminding me just where I'd been. I looked back and saw the abstract power that music has had in my life — and that it is having in yours today.

Music has a kind of primacy in our lives that we don't readily see. Think of music for a moment in its role as one of our technologies. Then try the question, "Which of our technologies came first?" Farming came late in history. Before farming, settled herdsmen and gatherers made clothing, knives, tents, and spears. But so did nomads before them.

Go back further: Archaeologists have shown that pictures and music were among the stone age technologies. Magnificent cave paintings survive along with evidence of rattles, drums, pipes, and shell trumpets. The Bible, that chronology of the Hebrew tribes, identifies musical-instrument making as one of three technologies that arose in the 7th and 8th generations after Adam.

When we begin tracing music-making as a technology, the issue begins to choke on its own ambiguities. Should we count the cave man drumming on a log? Should we count my dog, rhythmically thumping her tail on the wall? Is that instrumental music? So let's not include music as a technology unless it's associated with sophisticated music-making machines or organized schemes of scales or notation. After all, birds and whales were singing complex songs long before we humans walked the earth.

As we move back in time we find 4000-year-old cuneiform tablets that describe a diatonic scale. But the written record soon runs out. And the oldest artifacts are a few one-note whistles made by the Mesolithic modern humans some 25,000 years ago.

But then, in 1995, Slovenian archaeologist Ivan Turk made an astonishing discovery. Turk found a four-inch length of bone from the thigh of a cave bear — pretty minor except for two things: First, this bone is roughly 55,000 years old. That was well before modern humans. He found this bone among Neanderthal remains.

The real shock is what'd been done to the bone. Two holes, each a third of an inch in diameter, had been reamed into it. On either end, the bone had been broken where there were two more holes. We find that four holes were carefully cut into the bone, and they're not evenly spaced. It can mean only one thing.

This was a flute, and a sophisticated one at that. Musicologist Bob Fink, from Saskatoon, studies the scales these holes could've joined in producing. Since he has only part of the whole flute, he has to juggle possibilities. However, the uneven spacing means that this flute was tuned in a scale with whole notes and half notes. It was based on a scale that fits natural harmonics, the way all diatonic scales do.

Fink measures the hole spacings and juggles statistical probabilities of whole flute arrangements. Many academics have attacked his conclusions, but he always emerges standing on solid ground. He concludes, with near certainty, that this Neanderthal flute was tuned to either a melodic or a harmonic minor scale — a sound that's Oriental to the western ear — or sad, or exotic — a beautiful and haunting sound.

[Carol Ostlind sings a harmonic minor scale]

That scale by itself is very expressive music! Anthropologists have debated whether or not the Neanderthals even had speech. If they did, their range of sounds was certainly less than ours. But evidence has suggested that they buried their dead, protected their handicapped, and honored some Deity.

And now this! When William Congreve wrote that "Music has charms to soothe the savage breast," he missed the point. For where you have music you no longer have savages. The cartoon brutishness of the Neanderthal was created by 19th-century racism. Neanderthals had to be less than we, because they didn't look the same. We knew their brains were at least as large as ours, but we swept that under the rug.

So this bone flute delivers one more body blow to the myth of modern humans' superiority. Music is clearly as old as any technology we can date. Couple that with the sure knowledge that whales sing — that the animal urge to make music precedes technology — and music-making is absolutely the oldest technology.

Music weaves through societies with the least technology. Australian aborigines define themselves by their song, dance, musical instruments, and poetry. Music is the most accessible art and, at the same time, the most sophisticated. In almost any society, music-making will rank among the most complex technologies.

But our own experience tells us as much as archaeology does. Experience tells us that music is primal. It's not just a simple pleasure. Perhaps some of you have sung Vaughan Williams's Serenade to Music with its rich sixteen-part harmonies. In that remarkable piece, Vaughan Williams takes his text from Shakespeare's Merchant of Venice. The lady Jessica says to Lorenzo:

I am never merry when I hear sweet sounds of music,

[Carol Ostlind sings the passage]

And Lorenzo answers with a most remarkable observation:

[John Hurty sings the complete passage]

What an uncanny recognition of the truth of what you all do!

The reason is your spirits are attentive.

The man that hath no music in himself ... is fit for treason ...

And we know what he means! If we cannot respond to music, then something is missing. We are fit for treason.

Music helps us understand the human lot. Music is functional the way any worthwhile technology is functional. Its function is to put reality in terms that make sense. That means dramatizing what we see — transmuting it into something more than is obvious. Wallace Stevens wrote:

They said, 'You have a blue guitar,

You do not play things as they are.'

The man replied, 'Things as they are

Are changed upon the blue guitar.'

The blue guitar — music, or any art — does change reality. It turns the human dilemma around until we see it in perspective. Sometimes it takes us through grief and pain to do that. It disturbs us at the same time it comforts us. But it serves such fundamental human need. That is why music-making became the first human technology.

To see this process at work, let me play for a moment with one of my favorite composers of choral music. Josquin Desprez might well be the greatest composer who ever lived, and his greatness comes to rest on many of the reasons I've been hinting at. Josquin was a somewhat shadowy figure who defined the new music of the Renaissance. Some of you have sung his L'homme armé masses. I'm sure many of you have sung his little choral piece El Grillo — the one that makes a perfect imitation of a cricket.

When I was in graduate school, musicologists waged holy wars over Josquin's particulars. Today some of those particulars are in good order. We know Josquin was born in the northern part of France around 1440. That rough date comes from the 1459 records of a Milan cathedral which identify him as Jodocho de frantia biscantori. Jodocho de frantia was an Italian version of his name. Biscantori meant a young adult singer.

The spelling of his name changes from place to place and time to time. Historians finally saw that Josquin himself told us how he wanted his name spelled in a five-voice motet,Illibata Dei. He arranged the text to spell his name out in an acrostic puzzle.

Much of what we know about Josquin's life is spelled out that way in his music. When the Flemish composer Johannes Ockeghem died, Josquin wrote a heart-rending lament on his death. He has singers reading the roll of great composers who learned from Ockeghem, and Josquin's name heads the list. If he wasn't Ockeghem's actual student, he was certainly his spiritual heir.

The title of one Josquin mass, the Missa Hercules Dux Ferrarie, tells who his patron was, but this time Josquin did more. He matched the vowels of Hercules Dux Ferrarie to notes of the scale. The first e suggests the syllable re. The second vowel, u, suggests the syllable utwhich was the medieval do, and so forth. He got re-do-re-do-re-fa-mi-re — [sing] Her-cu-les Dux Fer-ra-ri-e. And that binding thread runs through every movement of the mass. Carol, could you sing the cantus firmus line from the Hosanna of the mass?

[Carol Ostlind sings Hosanna in Excelsis]

The only reason we remember an obscure duke of Ferrara is that Josquin wove that odd, and yet beautiful, memorial around his name.

Josquin died in 1521, just past 80. With his linguist's mind, his mathematician's mind — his wide-ranging genius mind — he redirected western music. At the end, he bequeathed his house and land to the Church of Notre Dame in Condé. He asked the church's singers to stop by his house during festival processions and sing his settings of the Pater Noster and Ave Maria. From that touching gesture music historians conclude that Josquin had a choir at Condé that could handle six-part harmony. That's a small thing to make a point of, but it reminds us how hard it is to tease a knowledge of the past from our scant records.

My favorite among Josquin's motets is an odd piece, Tu Pauperum Refugium — Thou art the Refuge of the Poor. It begins with soul-settling chords. Then it moves off into the complex polyphony Josquin so perfected 500 years ago. The text recites the attributes of God — "alleviator of weakness, hope of the exiled." But when Josquin reaches the line, "path for the erring," a strange thing happens. The grand order of the music seems to break down. The countertenor line stumbles about like a man lost in the woods. Where is it going?

Well, that's Josquin the linguist at work again. He's giving us an exegesis on the word error. Error comes from the same root as the word errant, which means embarked on a searching journey. Five hundred years ago, the two meanings were closer together. A person in error was a person searching for the truth. So Josquin's errant countertenors search for order.

Medical writer Lewis Thomas picks up on that exact same theme as he looks at DNA molecules. Surely DNA is nature's most wonderful invention. It's been the formative element of all life on Earth. DNA replicates us today just as it did when we were no more than primordial slime. DNA is a marvel in the way it flawlessly replicates any living species ...

Well, almost flawlessly. For the DNA molecule does err. Every now and then it makes errors and provides mutations that change living species. Thomas points out that if humans had designed DNA, they'd've found a way to get rid of that design flaw. And if they had, we'd still be no more than anaerobic bacteria. There never would've been a Josquin.

So DNA makes its errors. Living species do change. And I find a line of Chaucer, written a generation before Josquin's birth. In it, Troylus cries, "O weary ghost, that errest to and fro." Troylus tells the painful wandering of his own spirit since he lost Cressida. In this sense, erring is far more than simple blundering. It is searching for answers.

That's what Josquin was telling us. Human error is the path of our search. That's how DNA works. Through repeated error it searches out new life forms. That's the core of the creative process. To create is to wander off the path, to be errant. It is to start in one place so we might, in the end, find another place we never dreamed was even there. Thus music, and especially word-driven choral music, winds itself into the very fabric of our being. Josquin the musician was also Josquin the moral theologian. He had to be.

Move forward with me again, this time to the American Revolution. It should be no surprise that that expression of human freedom had to find expression in music as well as in armed revolt. I'll bet every one of you has sung William Billings's music at some time or another. Ask what music came out of Colonial America: We get Billings ahead of anyone else. Few sophisticated musicians think much of him. (I love his stuff.) Historians have made little effort to know Billings. Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians runs to almost 20,000 pages, and it gives Billings a page and a half.

Billings was born in Boston in 1747. He was poor and uneducated. He supported himself much of the time as a tanner. But he also took up music when he was young and was teaching choral singing by the age of 22. His biographers call him a gargoyle. He was blind in one eye with a short leg and a withered arm. But that's only the beginning. Billings practiced what a contemporary called "an uncommon negligence of person," and he was hopelessly addicted to tobacco — constantly inhaling handfuls of snuff. That may explain why he lived only to the age of 54. He had a stentorian tobacco-damaged, bass voice, and he seemed uninterested in any easy beauty of sound.

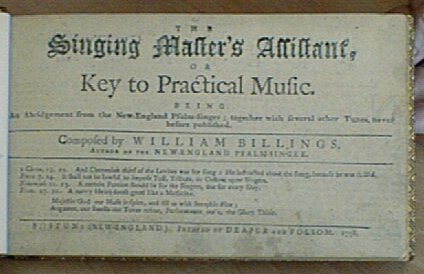

At 24, Billings published his first book of choral pieces. He called it The New-England Psalm-Singer, and Paul Revere engraved the frontispiece for it. He published five more volumes and several pieces of sheet music. But The New-England Psalm-Singer was the first book of American music. It began a tradition of musical grass-roots choral singing in America.

Image courtesy of the Beineke Library, Yale University

Billing's original Singing Master's Assistant

And Billings knew what he'd done. He delayed publication over a year — until he could print it on paper made in the Colonies. No English imports for Billings. I looked at a copy of Billings's book last month at Yale University, and the paper really does have its own idiosyncratic crudity. By the way, it included his song Chester which rivaled Yankee Doodle as an anthem of the Revolution:

Let tyrants Shake their Iron rod

And slav'ry Clank her galling Chains

We fear them not we trust in god

New englands god for ever reigns.

Ben Franklin had said art would flow to the west, to the new American Athens. What he got was Billings — no cultural continuity with anything. Billings's music emerged in the classical, Rationalist age with no trace of classical elegance. It is an artistic declaration of independence.

But to know Billings, we have to do more than just hear him, we have to sing him — four-square, almost-medieval harmonies, elaborate fugues, experiments with dissonance that foreshadow Charles Ives. He plays musical jokes, praises God, and dances into the erotic wonder of the Song of Solomon. Then he turns around and leaves us with one of the most exquisite short canons we've ever heard,

When Jesus wept, the falling tear

in mercy flowed beyond all bound.

When Jesus groaned, a trembling fear

seized all the guilty world around.

[Carol Ostlind sings the piece]

Suddenly, there, all of Billings' earthy quirkiness vanishes. It blows away in the face of that one lovely melody.

The essential genius of America, and of Billings, was recognizing that full independence from Europe could be gained only after we'd formed our own cultural roots. And that revolutionary spirit continues to touch the American Choral tradition in our century.

Two years ago I heard Robert Shaw direct Benjamin Britten's War Requiem — a setting of a poem by Wilford Owen. Owen was an English soldier, killed in the last days of WW-I. In 1948 I sang under a Shaw protege. Shaw was, by then, the young wunderkind whose revolutionary notions of choral singing had the same radical stamp as Billings. He was transforming American choral singing.

I was studying calculus and mechanics in those days. And I was singing — surrounded by returning WW-II veterans. I'd survived the war by being just a little too young to go. The students around me — some damaged, some not, had survived by being luckier than the ones who died. I went on into engineering and

teaching. All the time I sang everywhere I could. In 1974 I was in Jugoslavia singing with the Serbian Orthodox Cathedral and working in the International Center for Heat and Mass Transfer.

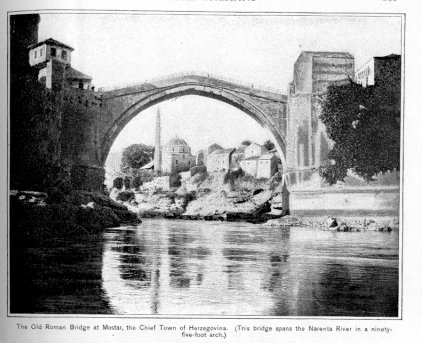

That August I drove down through Bosnia, and through Mostar, to a conference in Dubrovnik. The car carried my wife and me, our two boys, and the conference proceedings. We stopped near the famous Mostar Bridge for our sandwiches and juice. Bees hummed in the summer air, and the graceful bridge reflected in the river water.

The Bosnians were nice to us. A couple took us into their house that night. Their daughters slept on the couch. Other Jugoslavs were nice to us too. But they told jokes about the Bosnians. They told the same jokes I once told about the Polish. I recently saw a picture of what was left of the Mostar bridge. Croatian guns had pounded it into rubble. And I know I'll never tell Polish jokes again.

Now here was Robert Shaw again, still at it, a half century later. So much comes back: Those ex-GIs; Art Winship, who finished college in a wheelchair; John Wagner, who'd been a foot soldier in the terrible 1945 German counteroffensive. That whole part of my life had played to the background of Shaw's musical methods.

The students with me had been through the same things Owen wrote about. They told me about senseless death. Then I heard the War Requiem, and I listened as Owen dreamed up the ghost of a soldier he'd killed. The ghost speaks:

I am the enemy you killed, my friend.

I knew you in this dark; for so you frowned

Yesterday through me as you jabbed and killed.

I parried; but my hands were loath and cold.

Let us sleep now . . .

Twenty years ago in Jugoslavia I sang and studied coal gasification. I listened to Bosnian jokes and sat by Mostar's lovely bridge. Now I heard Wilfred Owen: "It seemed that out of battle I escaped." Well, he did not escape, nor did Hugo Distler, nor in the end, do we. Music sharpens and hones our understanding of those things. Music tells us who and what we are. Music is the oldest technology.

Pathologist Lewis Thomas, whom I mentioned a moment ago, talks about the Ik. And the Ik do not sing. The Ik were nomad hunters in Northern Uganda. The government made their hunting grounds into a national park and relocated them. They had to take up farming.

In 1972, anthropologist C.M. Turner wrote about the Ik in their new life. They laugh only at one another's misfortunes. They teach their children to steal food from the old. They are solitary and ill-humored. "They breed without love," says Thomas, and, "They defecate on one another's doorsteps." The social roles of the Ik have been unthreaded. And with that, they've lost all sense of community. Each Ik is now an isolated one-man tribe unto himself. Interdependency is gone; and the Ik no longer sing.

So Thomas turns his attention to animal and insect music-making. What does he find? He finds that music always accompanies community. At first we hear only babble. It takes patience to sift out syntax and sense. But syntax and sense is there. Termites constantly rap their heads against the floor. It sounds random and senseless. Yet when biologists record the sound, and study it, they find pattern, variety, even phrasing.

Ask yourself how an alien might react to a Bartok quartet. I can answer that one. I was alien to string quartets the first time I heard one. I didn't hear music. I heard only the cacophony of termites banging their heads. Bartok came clear to me in 1952 when I made a strange experiment. I covered my ears for a moment and only watched the four players. Suddenly I saw conversation. I saw a ballet. I saw the players trading ideas. After that the music made sense. I've loved Bartok ever since.

Now I know what I'd really seen in that instant. I'd seen what we all crave — what we cannot live without. I'd seen community. For the next forty years I involved myself in music. Choirs, chamber groups, opera — always finding community in the intimacy of music-making.

Thomas takes a term from physics, the musical term ensemble. An ensemble is a group of atoms whose individual action seems chaotic, but whose aggregate action displays order and sense. That's what the Ik had lost. They have no ensemble. Their old roles in each other's lives are gone. The threads of community have been pulled out. Each Ik is what you or I might become if we let ourselves be stripped of community. And the surest sign of that isolation is almost too terrifying to think about. It is that the Ik no longer sing.

But you do. Music and ensemble are there to sustain you. Don't ever lose that!

SOME SOURCES

Jessica and Lorenzo's conversation takes place in Shakespeare's Merchant of Venice, Act V, Scene 1.

Stevens, W., The Man with the Blue Guitar, The Collected Poems of Wallace Stevens. New York: Albert A. Knopf, 1982.

Early Music. editorial sidebar in Science, Vol. 276, 11 April, 1997, pg. 205.

Fink, Bob, NEANDERTHAL FLUTE: Oldest Known Musical Instrument Plays Notes of Do, Re, Mi, Scale. article available on the internet at http://www.greenwych.ca/fl-compl.htm

Reese, G., Josquin Desprez, The New Grove Dictionary of Music & Musicians. (Stanley Sadie, ed.), Vol. 9, NYC: MacMillan Pubs Ltd., 1980, pp. 713-738.

I am grateful to Carol Lienhard for considerable expertise and assistance with Josquin. The only recording of Missa Hercules Dux Ferraria that I've been able to find is one I sang myself: Music of Bach, Josquin, and Hindemith, The Berkeley Chamber Singers, Music Library Recording No. 7075, 1959. Josquin's Ave Maria, El Grillo and L'homme armémasses have been recorded repeatedly.

Thomas, L., The Medusa and the Snail: More Notes of a Biology Watcher. New York: Bantam Books, 1980.

See entries under err, error, and errant in the Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed. (J.A. Simpson and E.S.C. Weiner, eds.) Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1989.

I'm grateful to John Snyder, UH Music Department and to Jeff Fadell, UH Library, for their counsel.

For Josquin's Tu Pauperum Refugium, see, e.g., Davison, A.T., and Apel, W., Historical Anthology of Music, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1957, pp. 92-93 and 249

McKay, D. P., Billings, William. The New Grove Dictionary of Music & Musicians. (Stanley Sadie, ed.), Vol. 2, New York: MacMillan Publishers Ltd., 1980, pp. 703-705.

Silverman, K., A Cultural History of the American Revolution. New York: Columbia University Press, 1987.

The Houston Symphony, the Houston Symphony Chorus, and the Fort Bend Boys Choir performed Benjamin Britten's War Requiem, Op. 66, on Sunday, November 14, 1993 at Jones Hall in Houston, TX. The soloists were Lorna Haywood, Soprano; Stanford Olson, Tenor; and Davis Wilson-Johnson, Baritone. Britten's text is woven from poems by Owen and elements of the Latin Requiem Mass. Sandwiched between the Pie Jesu and the Dies Irae we hear:

Be slowly lifted up, thou long black arm,

Great gun towering toward Heaven, about to curse;

Reach at that arrogance which needs thy harm,

And beat it down before its sins grow worse;

But when thy spell be cast complete and whole,

May God curse thee, and cut thee from our soul!

Thomas, L., The Lives of a Cell: Notes of a Biology Watcher. New York: Bantam Books, 1975, pp. 22-28, 126-129

Turnbull, C.M., The Mountain People, New York: Simon and Shuster, 1972.

Tien, C.L., and Lienhard, J.H., Statistical Thermodynamics. New York: Hemisphere Pub. Corp., 1979 (see especially, Chapter 8, "Statistical Mechanical Ensembles.")