Frankenstein, Faust, and Pygmalion

for the Society for Technical Communications (STC) Conference,

Westchase Hilton Hotel, 9:00 AM, Friday, October 12, 2001

by John H. Lienhard

Mechanical Engineering Department

University of Houston

Houston, TX 77204-4792

713-743-4518

jhl [at] uh.edu (jhl[at]uh[dot]edu)

The laboratory is down the stairs -- out of the light. We see bubbling glassware and arcane electromechanical machines. The scientist himself is lonely, naive, and egomaniacal. He tells The Foundation about his humanitarian aims. But you and I know that something in his animal nature drives him to darker things.

The laboratory is down the stairs -- out of the light. We see bubbling glassware and arcane electromechanical machines. The scientist himself is lonely, naive, and egomaniacal. He tells The Foundation about his humanitarian aims. But you and I know that something in his animal nature drives him to darker things.

The image of the mad scientist is so strong, we'd be foolish to shrug it off as just another piece of pop-fiction. It's an image we all revert to, now and then, as we think about technology. That's why any of us who write on the subject need to ask where the image comes from and what it really means.

It probably traces to the Faust story; so let's begin with the real Faust -- the historical Faust. He was a shadowy figure in early sixteenth-century Germany, a kind of self-styled magician and hell-raiser. One place he shows up is in the records of the city of Ingolstadt. And, in a moment, that town comes back to us with the most remarkable mad scientist of them all.

Storytellers took up the legend of Faust and recast him in the language of the Protestant Reformation (which was, just then, running at full force). The Faust we know -- the Faust who sold his soul for knowledge -- took his present form in 1607, in Christopher Marlowe's Tragicall History of Dr. Faustus.

But that was also just as modern science was finally taking on its present shape and conventions. Thirteen years later, in 1620, Francis Bacon would tell us that

The empire of man over things is founded on the sciences ... for nature is only to be commanded by obeying her.

And here we have, almost for the first time, an explicit statement of our modern notion that science and our technology are wed to one another. Bacon believed science should give rise to new technology.

In fact, that's not really how things have ever worked -- even today. Inventors usually have the idea of the machine before they understand the science that makes it run. Windmills and waterwheels came long before we had any knowledge of the fluid mechanics that explain their workings. Steam engines preceded thermodynamics. We had the telegraph before we knew electric field theory.

But, by 1620, we were nevertheless beginning to see the world through a very new set of lenses. I strongly suspect the Faustian mad scientist is fictional shorthand for the change that took place at that point. We use the image to express our fear that science won't just make machines. It'll also turn us into machines.

The Faust that you and I recognize came later: the Faust of the German poet Goethe, the Faust in the opera. Goethe wrote about Faust two hundred years after Marlowe and Bacon. By 1800, science had gone too far in the direction of objective observation and pure reason. Our thinking had reached the point where it would have to shift once more.

By 1800, we knew it was time to leave the mentality of eighteenth-century objective rationalism. The Romantic poets were telling us we had to rediscover the subjective forces within ourselves. And Goethe was one of those Romantic poets. In Goethe's version, Satan offers Faust all knowledge in exchange for his soul. Faust accepts. The rest of the play tells of his descent into hell. But before they cut a deal, Faust and the devil argued back and forth, and Faust said a very curious thing to Satan.

Werd' ich zum Augenblicke sagen:

Verweile doch! du bist so schön!

Dann magst du mich in Fesseln schlagen,

Dann will ich gern zu Grunde gehn ...

That obviously needs explanation. But I'll hold off reciting it in English until I've covered a few more bases. I first encountered that verse when I was only eleven. I heard it in movie. The hero quoted one line of it to the heroine: Linger a while, thou art so fair. Somehow, I found that strangely compelling and never forgot it.

Now, jump ahead to an evening in 1980, in Lexington, Kentucky. I'd been offered my job here in Houston. It was going to be a good job, but I didn't want to leave Kentucky.

Then, on one magical evening, my dog and I walked out through the University farm, behind our house. The dog ran through the high grass. Fireflies were out. Waves of firefly light rippled outward -- as far as the eye could see. It was a night of such perfect crystalline beauty as to melt your heart. And, at that moment, I knew I would accept the Houston job.

Now, is that a crowning piece of illogic? Well, when I finally found the full text of the Goethe quotation, I realized what'd happened on that surrealistically lovely night in Kentucky.

Faust uttered the line while he negotiated with the Devil. You see, Faust didn't strike a bargain with the Devil. Instead, he made a bet. Faust bet that he could never be lured into settling down on any Earthly pleasure -- that his spirit would remain restless. The Devil agreed to the bet, and that's when Faust uttered those remarkable lines. He said,

When I say to the Moment flying:

'Linger a while -- thou art so fair!'

Then bind me in your bonds undying,

And my final ruin I will bear!

He tells Satan that he'll never settle down on any one good thing. He, Faust, will never be satisfied. The devil says, "Oh, yes, you will."

Faust's claim was a primary Romantic sentiment: Driving restlessness is the mainspring of the creative person. Faust snaps back at Satan, "When did the likes of you ever understand a human soul in its supreme endeavor?"

Goethe spent forty-one years, 1790 to 1831, on and off, writing Faust. During those same years, Watt's engines marched out of England and transformed the world. And Wordsworth wrote,

Huge and mighty forms that do not live

Like living men, moved slowly through the mind

By day, and were a trouble to my dreams.

Huge iron machines entered our world propelled by our Faustian needs. All the while the Romantic poets told us we had the intellectual power to shape nature. William Blake, one of the first Romantic poets, caught that idea when he wrote, I will not rest from mental fight.

So when I faced overwhelming contentment that night in Kentucky, I knew on some visceral level that I'd have to turn my back on it.

Romantic restlessness is what really drove all the heroic nineteenth-century technology. It's what drove four American engineers who'd never seen a canal to began building the almost four-hundred-mile Erie Canal in 1817. It's what sent Marc Brunel off to build an unheard-of tunnel under the Thames River in 1825.

The engine behind that vast explosion of technology really was, and (I believe) still is, Romantic discontent with anything other than a world being rebuilt over and over in the human heart. It's Faust raging at Satan that he would never say to any rare and perfect moment, Linger a while, thou art so fair. Faust teased at the Romantic mind of the nineteenth century.

The wild inventor Nikola Tesla emerged toward the end of the century as the popular embodiment of the mad scientist. He'd been a student at the Austrian Polytechnic Institute when he brashly suggested that electric motors would run better on alternating current. His professor asked where a bright student came up with such claptrap; there was no way to make an alternating-current motor.

Six years later, in Budapest, Tesla walked through the park at sundown, reciting some sad lines from Goethe's Faust. Tesla thought about that scene just before the devil arrived with the answer to Faust's aching need to know everything. Faust, having failed to uncover the secrets of nature, mused upon sunset and the end of life, and he said,

The glow retreats, done in the day of toil;

It yonder hastes, new fields of life exploring;

Ah, that no wing can lift me from the soil,

Upon its track to follow, follow soaring!

That's when it hit Tesla: Maybe Faust had been ready to linger into that lovely moment before Satan arrived. But he, Tesla, was still in motion. He suddenly saw how the leading and following fields in motors and generators could be arranged to create and use alternating current.

Three years later, Tesla went to work for Edison in the United States. He tried to interest Edison in alternating current but was told that the idea was downright un-American. Tesla and Edison soon parted company. Tesla managed to get funding from the financier J. P. Morgan, and he issued a series of a/c patents starting in 1887. He soon convinced George Westinghouse to put his money into the development of a/c power systems.

Edison's response was maniacal. He launched an appalling campaign to discredit Westinghouse and Tesla. The idea was to show that alternating current was too dangerous to use. He invited reporters to demonstrations where he placed stray dogs and cats on metal sheets and electrocuted them with a thousand volts of alternating current.

Next, Edison took out a commercial license to use alternating current. The world found out why after he'd made clandestine visits to one of the New York state prisons. He'd created the electric chair. Now the American public would see what alternating current could do to a human being.

Before the chair was used on a fellow named William Kemmler, Edison's people started killing larger animals in their demonstrations. They asked, Is this what your wife should be cooking with?

When poor Mr. Kemmler was taken to the chair to be (as the Edison people put it) Westinghoused, the voltage was too low. A half-dead Kemmler had to be electrocuted a second time to finish him off. All this served Edison's purpose, of course. There was no need for Kemmler's passing to be a pleasant one.

In the end, Tesla's alternating current prevailed, but it took twenty years for Edison to admit defeat. The electric chair also prevailed into our lifetimes.

And so we truly are drawn back to that quaint medieval town of Ingolstadt. That other-world where the Faust-thing all began. In 1816, another restless soul showed up in Ingolstadt. Unlike Faust, this person was completely fictional, but, like Goethe's Faust, he clearly represented the Romantic restlessness of his times.

He was Victor Frankenstein. He came down out of an elegant Swiss home and went to Ingolstadt to study medicine. Mary Shelley's Frankenstein went beyond Goethe's Faust in a couple of ways.

For one thing, knowledge alone was no longer enough. Frankenstein had to create life as well as understand it. It'd been alchemy that'd served Faust. Frankenstein rode electrochemistry on his trip to Hell.

Later in the nineteenth century, Faustian mad scientists added hypnotism and then the mysterious new forces of radiation -- X-rays and radium. The early twentieth century gave us Faustian technologists: Captain Nemo and the huge soul-eating mechanical city of Metropolis. And today's mad scientist is wed to his computer or to biochemistry. Each new discovery calls Faust or Frankenstein forth in some new incarnation.

Robert Louis Stevenson added yet another twist when the monster Mr. Hyde emerged from his gentle Dr. Jekyll. That, of course, happened when Jekyll lost control of his knowledge. Jekyll and Hyde touched something about our nature that we all understood instinctively.

But let us come back to Frankenstein. Mary Shelley was only nineteen when she wrote it. She'd gone off with Percy Shelley, Lord Byron, and a few of their friends to Switzerland. One night someone threw out a challenge that they should all try their hand at writing a Gothic horror novel.

Mary Shelley was the only one who who really carried it off. In the introduction to one edition of her book, she offered a theory of invention along with the history of her idea.

Everything [she says] must have a beginning. That beginning must be linked to something that went before. The Hindoos give the world an elephant to support it, but the elephant stands on a tortoise. Invention [is not created] out of the void, but out of chaos. The materials must first be there.

And what were the materials she worked with? She continued:

Many and long were the conversations between Lord Byron and Shelley. During one of these, the principle of life [was discussed -- whether it could ever be] discovered. They talked of the experiments of Dr. Darwin who preserved a piece of vermicelli till by some extraordinary means it began to move ...

Perhaps a corpse [could] be reanimated; galvanism [hints of] such things: perhaps the component parts of a creature might be manufactured, brought together, and endued with vital warmth.

In the most arresting part of her account, Mary Shelley tells how her story formed from the chaos of their conversations.

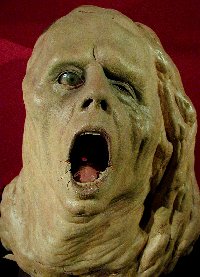

Night waned upon this [talk. Even] the witching hour had gone by. When I placed my head on my pillow, I did not sleep, nor could I be said to think. My imagination, unbidden, possessed and guided me, gifting the successive images that arose in my mind with a vividness far beyond the usual bounds of reverie. I saw -- with shut eyes, but acute mental vision, -- [a pale] student of the unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together. I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine, show signs of life, and stir with an uneasy, half vital motion.

And how would Victor Frankenstein react?

Success would terrify [him. He would rush] from his odious handy-work, horror stricken. He would hope that slight spark of life would fade; that this thing would subside into dead matter.

[He falls into] sleep; but he [wakes]. The horrid thing stands at his bedside, opening his curtains, and looking at him with yellow, watery, but speculative eyes.

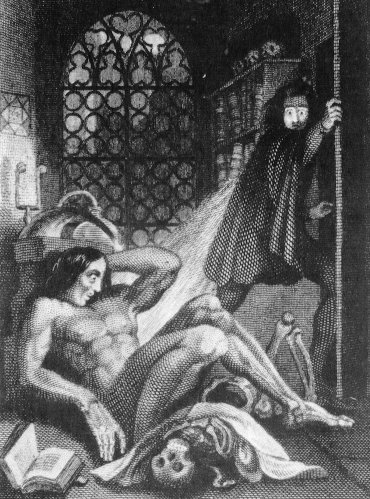

Frontispiece of the 1831 edition of Frankenstein: A Modern Prometheus

We do experience a moment of detachment just before sleep. As Mary Shelley reached that moment, she was still replaying the evening's conversation in her mind. Suddenly, bits of talk fused into the most perfect tale of horror ever written. Just as sleep came, her Victor Frankenstein blinked awake, transfixed by the same brooding gaze that's held us all ever since.

Before Mary Shelley wrote Frankenstein, she'd read Erasmus Darwin's ideas about the spontaneous generation of life in rotting food. Darwin was a doctor and poet. He was also Charles Darwin's grandfather. He'd done experiments in which he left a bowl of vermicelli out until he saw that tiny worms had come into being in it. Of course, we know about larvae and maggots; so we're less likely to be impressed with Darwin's observation.

But the belief in the spontaneous generation of life had been around for a long time, and Darwin's experiment brought it into focus for Mary Shelley. If we could create elementary life in yesterday's pasta, what more might we do in a modern nineteenth-century laboratory?

Sixty years later, another English visitor summered in the Swiss Alps. He was the physicist John Tyndall. And, like Mary Shelley, he also thought about generating life spontaneously. In spring, a nearby lake was clean and lifeless. By summer's end it teemed with life. If you weren't careful, he said, you could think that life arose spontaneously in the sterile melted snow.

Today, we know Tyndall for his work with heat, light, and sound. We forget his work on microorganisms and airborne disease, even though it stands right along with Pasteur's and Lister's. It was work that he'd begun in the 1860s, when he was studying light. He wanted to make air dust-free. So he created something we call the Tyndall Box. He coated the walls inside a sealed box with glycerin.

After three days, all the particulates in the air stuck to the walls and left the air in the box as clean as a whistle. Tyndall had made the air optically pure. He showed that beams of light are invisible when they enter a window and pass through clean air.

By now doctors knew that dirt and dust caused disease. They also suspected that germs might be major agents of disease. Tyndall put those ideas together. He saw that by cleaning the air he'd removed the vehicle that carries microorganisms.

To make his point, he exposed test tubes of urine to the clean air in a Tyndall box. Bacterial life grew in the test tubes under normal air. They stayed sterile in the box. So he repeated the experiment with meat, fish, and vegetables. Same story. None of them putrefied in clean air, either.

He made his work public in 1870. Then the fun began. Biologists attacked him. One of them, a believer in spontaneous generation, scalded him for "quitting his own metier." He told Tyndall that the germ theory of disease was the business only of biologists and physicians, not of physicists.

Well, I'm afraid we still hear a lot of that talk. Tyndall simply shot back: If that were true, then the chemist Louis Pasteur shouldn't be allowed to study germs. In any case, as we moved from Shelley to Tyndall, our view of manipulating human life changed. Now that manipulation was no longer a metaphor or a story.

It was becoming something we might actually have the tools to achieve. So medicine really did begin reshaping humankind in earnest. You all know the story of King Pygmalion who carved the perfect woman in stone and then fell in love with her. Aphrodite took pity upon him and endowed Galatea with life.

The problem is, that's not how things really work. Our fascination with Pygmalion began rising in the nineteenth century. Charles Babbage, who first conceived the programmable computer, had visited a museum of mechanical wonders in London when he was just a child.

There he saw a wonderful robot/music box with two nude dancers moving about on the top. Later, he wrote of it,

One figure ... glided ... along. ... The other was [a] danseuse. ... Her eyes were full of imagination and irresistible.

Later, as a grown man, he managed buy that model for himself. I rather suspect that the idea of animating that sculpted beauty was in Babbage's mind as he conceived his mechanical human brain.

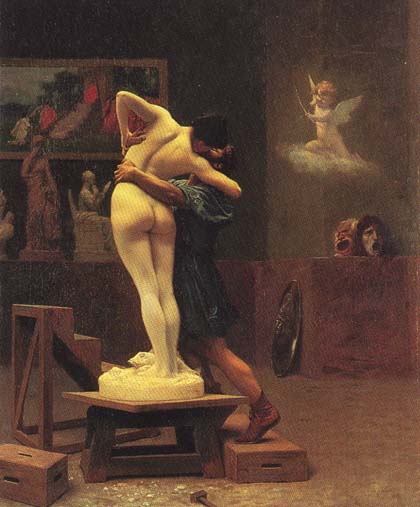

In the latter ninteenth century, the famous French salon artist Jean-Leon Gérôme did two rich Romantic paintings of Pygmalion and Galetea that were widely copied and circulated. The Pygmalion story truly laid its hand on the Victorian imagination.

Gérôme's painting of Pygmalion

Small wonder that the worm of doubt began creeping into our thinking about Pygmalion. George Bernard Shaw wrote his play Pygmalion in 1913. Now Pygmalion was the crusty Henry Higgins, a linguist with very little human compassion. And his creature Galetea is the cockney flower girl Eliza Doolittle.

Higgins' effort to create a perfect woman yielded an Eliza with the air of a lady and with London street smarts -- someone the naïve Pygmalion/Henry Higgins didn't know how to cope with. And Pygmalion stayed with us. After World War II Henry and Eliza reemerged in the wonderful musical, My Fair Lady.

We've replayed the Pygmalion legend again and again with our technologies. Let me tell you another version that occurred during the gathering days of World War II:

Our Air Force badly needed better planes, and lots of them, so the Air Force went to the automobile manufacturers for help. In 1941 General Motors started making B-29 bomber parts, and Ford set up a plant to make B-24 Liberator bombers at Willow Run.

Then General Motors hired Don Berlin, the man who had designed the P-40. The P-40 was the fighter plane that the Flying Tigers had been using in China. Up to then, airplanes had been virtually handmade. The biggest airplane company could turn out three planes a day, while automobile makers made three cars a minute.

Henry Ford, for one, had no appreciation for how hard it was to adapt a good airplane design to his mass-production methods. He rashly claimed that, freed of government red tape, he could make more than a thousand airplanes a day.

Don Berlin went to the Air Force with a plan that linked his skills as an airplane designer with the GM style of mass production. He showed them a new fighter plane design, the XP-75. The XP-75 would outperform all our experimental fighters, and he meant to avoid the problems these planes were giving us. His plan was simple. He would use the best parts of other airplanes: the wing of the P-40, the tail of the A-24, the landing gear of the P-47, and so on.

Like the creatures of Pygmalion and Frankenstein, the XP-75 was to be an assembly of perfect parts. You will find it no surprise that the result resembled Frankenstein's creature in more ways than one. It was an oversized monster that didn't begin to compete with planes designed from the ground up. The Air Force was so sure this beast would succeed that it tooled up to mass-produce it. When the whole idea was finally scrapped in 1944, it'd cost over nine million dollars -- a huge sum back then.

The XP-75

A designer has to seek out the harmony among parts that make up a design. A designer must see the design whole. Sophia Loren once remarked that all her parts were wrong. Her nose was the wrong shape, her mouth was too wide, and so on. Yet who could fault her beauty?

The components of a good design have to make sense in the context of the whole. The XP-75 was only a collection of fine parts. It was not a whole airplane.

Indeed, few things we ever make are really built whole. As we struggle to build and rebuild our world and ourselves, that comes home to haunt us. We reenact Faust and Frankenstein over and over. For they truly are our constant companions in this technology-dense world.

That, of course, is where you and I come in. For our task is to tell the story of the things we create. Since our words inevitably fall upon the inner ear of the public, we cannot help but to call up the mad scientist.

Technology is the prime agent of change and improvement in modern life. I can say that with utter conviction. Yet, we all need to live in constant awareness that no technology is without some facet of monstrousness. Faust is always with us. I'd be very foolish to forget that as I join you in celebrating all our machines do for us.

SOME SOURCES

Katz, B.M., Technology and Culture: A Historical Romance. Stanford. CA: The Portable Stanford Book Series, 1990, See especially, pp. 100-101.

There are countless translations of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's Faust available. Check your library. My translation of the four lines is a compromise among several versions.

Cheney, M., Tesla: Man Out of Time. New York: Dell, 1981 (note especially Chapter 5).

O'Neill, J. J., Prodigal Genius: The Life of Nikola Tesla. New York: David McKay Co., 1944.

For the Mary Shelley text, see, e.g., Jennings, H., Pandaemonium: 1660-1886: The Coming of the Machine as Seen by Contemporary Observers. New York: The Free Press, 1985, Frankenstein, pp. 141-142. (I haven't shown my fairly extensive cuts in Mary Shelley's text. You might like to see the full text in a copy of the 1819 edition of Frankenstein: A Modern Prometheus.)

Tyndall, J., Essays on the Floating-Matter of the Air. (Reprinted from the New York Edition of 1882, R.N. Doetsch, ed.) New York: Johnson Reprint Corp., 1966.

Holley, I. B., Jr., A Detroit Dream of Mass-Produced Fighter Aircraft: The XP-75 Fiasco. Technology and Culture, Vol. 28, No. 3, July 1987, pp. 578-593.

Yenne, B., The World's Worst Aircraft. New York; Barnes & Noble Books, 1987, pp.66-67