In Which Ford Forgets

Today, Henry Ford forgets what he once knew. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Historian John Staudenmaier asks how Henry Ford grew so hidebound after the stunning brilliance of his early years.

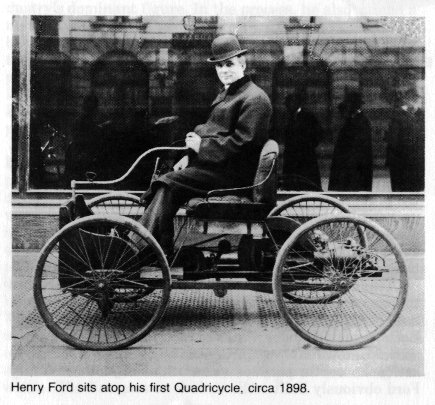

Ford, born during the Civil War, began making cars when he was 40. Few roads were paved, and there was no system of service stations. Ford understood that successful cars had to be rugged, and you had to be able to fix them yourself.

Ford began making cars the way everyone else did -- by hauling material to work stations where people did many operations. He first broke with orthodoxy, not by creating his assembly lines, but by convincing stockholders that cars weren't just for the well-to-do. He went for higher production and lower prices.

He gave us the Model T in 1908, the soul of simplicity and ruggedness. It was so successful that he didn't have to predict sales. He could sell every car he made. So he developed faster production methods. By 1914 he'd invented the moving assembly line.

Workers hated the dull repetition of the moving line. Worker turnover grew astronomically. Ford innovated again. This time, he doubled wages from $2.50 to $5.00 a day. He cut the working day from 9 to 8 hours. He shared profits with his workers.

For that the press made him into a folk hero. But he was also becoming a paternalistic boss, checking up on workers' home lives and habits. That went more or less unnoticed at first.

By 1927 Ford's company was worth 700 million dollars. But success was working its mischief. Ford had built success by looking down the road at the future. Now he was only 63, and he'd long since begun putting up walls and putting on blinders. He'd isolated his plants physically, refused to unionize, and tried to manufacture his own rubber and steel. Worst of all, he'd stopped looking ahead. He'd stayed with his own formulas for success.

In the early '30s the great Mexican muralist Diego Rivera celebrated Ford's factories with a set of murals. Rivera showed Ford's plants spilling out into the world as a transforming force. He didn't realize how Ford had closed in on himself. By then Ford was pouring millions into a strange museum at Greenfield Village. He moved an entire old watch shop and a Cotswold cottage from England. He built a private nostalgic dream world.

Even as Rivera painted, General Motors had displaced Ford as the premier automaker. The Model A and the V-8 engine couldn't stem the tide. In the end, Staudenmaier says, the virtues of "patience, hope, imagination, humor, and a willingness to fail and to disagree" make us great. We receive those virtues by being open to external realities. Those are the just the virtues Ford cut himself off from -- right at the peak of his success.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Staudenmaier, J.M., Henry Ford's Big Flaw. American Heritage of Invention & Technology, Vol. 10, No. 2, Fall 1994, pp. 34-44.

Image courtesy of the Ford archives

Henry Ford's "Quadricycle" Automobile, ca. 1898

Stereopticon Image courtesy of Margaret Culbertson

Workers leaving the Ford Motor Company plant in Detroit, MI