Grain in Abu Hureyra

Today, let's watch an archaeologist do detective work. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Abu Hureyra is an archaeological site in Northern Syria. Theya Molleson has been studying skeletons of the people who lived there between 8000 and 5000 BC. She asks an old question: "How do we change technologically?" The skeletons answer her.

Let's begin with big toes on the women's right feet: They're bent upward. How odd! Did these late stone age people play some strange sport? Did women have to kick a stone football about?

Then someone pointed to Egyptian pictures of kneeling supplicants. The big toe bends against the ground. Sure enough, Molleson's women had enlarged tibias where the knee would meet the ground. But why should women spend long periods kneeling? And why only the right toe? Back to the skeletons: Women's lower backs and elbows show signs of having been worked very hard.

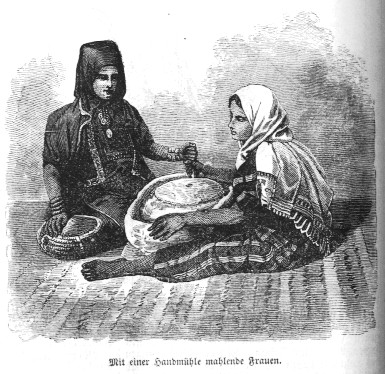

Finally Molleson has the picture. Imagine you're a woman grinding grain on a long flat quern or grinding stone. You kneel with your left foot crossed over the right to give you a stable three-point suspension. You roll a cylindrical pestle back and forth over grain on the stone. Backbreaking work!

Of course, that means these people had agriculture 9500 years ago. It also means they differentiated tasks among men and women. Men hunted and grew grain; women ground the grain.

That explains another skeletal defect. Early skulls of both sexes show badly fractured teeth. The problem with "stone ground" grain is that stone flakes into the grain. Stone fragments and partly ground kernels do terrible damage to teeth over the years.

Later, Molleson finds less tooth damage. She finds, instead, that just a few women have deep grooves in their front teeth -- the same grooves you find on the teeth of modern Paiutes who use their mouth as a third hand to hold canes when they weave baskets. Around 6500 BC, Abu Hureyra women invented weaving, but weaving was a job that only a few craftswomen did.

And weaving led to the invention of sieve making. So the problem of tooth damage was partly solved by sifting out stones and hard kernels. Later, the Abu Hureyrans acquired another new technology that finished solving the problem of tooth destruction. By 5300 BC they'd learned to make clay pots in which to soak grain and cook cereal. They'd begun eating porridge.

Those old bones say much about how technology went into high gear in the late paleolithic period. Soon the kin of these people would add the wheel, cloth, metal-working -- and writing. Molleson's skeletons were first in the same line of technologists who are now making space ships -- and genetically engineered food.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Molleson, T., The Eloquent Bones of Abu Hureyra. Scientific American, Vol. 271, No. 2., August 1994, pp. 70-75.

Stereopticon photo courtesy of Margaret Culbertson

A Central American saddle quern very nearly the same as those in ancient Abu Hureyra

From an 1882 German Bible

A hand quern typical of Biblical times -- still little evolved three thousand years later