Wood

Today, we revel in a wealth of wood. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

North American settlers found more wood here than they'd ever known. Millwrights and carpenters had deforested Europe long since. Here was a vast ocean of trees. What we were to become, this side of the Atlantic, was anyone's guess. Only one thing was sure. Our new life would be carved from wood.

An odd spinoff of all that wood was that it also made us iron-rich. In the early 1700s we smelted iron with charcoal. England had iron, but no wood to reduce it. She'd been using European iron for a long time. Now she came to us.

If Britannia ruled the waves, she did so in wooden ships. Shipbuilding ate wood. We didn't supply only wood. We also supplied finished ships. When the American Revolution began, one third of the vaunted English navy was American built.

Still, our technologies weren't very creative, not yet. We were still infants wed to the technology of the mother country. Creativity is freedom. It is independence. And our independence, when we finally claimed it, had to be shaped in wood.

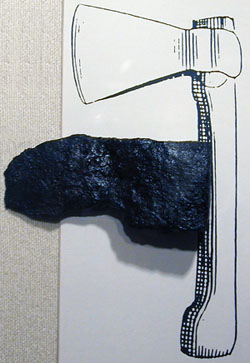

So it's no surprise that one of our early technological triumphs was the modern felling axe. European axes had straight handles. Their blades had a far more awkward balance.

We evolved the graceful curved handle you and I know so well. We shifted the blade's center of gravity. It was a huge improvement. That axe, which we take for granted, could fell trees three times as fast. It wrote our American history.

We evolved the graceful curved handle you and I know so well. We shifted the blade's center of gravity. It was a huge improvement. That axe, which we take for granted, could fell trees three times as fast. It wrote our American history.

Finally England learned to make coke from English coal. Coke is what's left when you bake the volatile materials out of coal. It's almost pure charcoal. It burns hot and clean. By 1800 England was producing the finest iron in the world.

We fell behind in iron, but we still had all that wood. When our railroads went West, we took the wooden truss bridge to its limits. England kept building iron bridges. We opened the West with wooden steamboats.

Our lumber saws were faster, but they wasted far more sawdust. For us, wood was as free as air. We perfected wood-shaping tools. We learned to make interchangeable wooden parts. We even made wooden clockwork for a time.

We eventually reached childhood's end. We cleared the land and ran out of free wood. By Japanese or English standards, we're still wood-rich. But today, wood is a farm product -- something we plant, then harvest 20 to 75 years later.

We eventually reached childhood's end. We cleared the land and ran out of free wood. By Japanese or English standards, we're still wood-rich. But today, wood is a farm product -- something we plant, then harvest 20 to 75 years later.

Now we build in plastic and steel. But what we are was carved from wood, perfumed in sawdust, seasoned, and varnished. And the underlying grain of America is still --the grain of wood.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Hindle, B., The Artisan During America's Wooden Age. Technology in America: A History of Individuals and Ideas. (C.W. Pursell, ed.), Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1986, Chapter 2.

See also Engines episodes No. 383 and 779 for more on wooden construction.

Modern axe image courtesy of Wikipedia Commons. Other museum photos by J. Lienhard.