Wooden Clocks

Today, a cheap clock is worth more than it seems. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Imagine early 19th-century life in the American Midwest. Imagine the primitive rural land that gave us Abe Lincoln. The survival technologies in that harsh land were very like the ones that people used in medieval Europe.

The last great technology to appear in medieval Europe was the mechanical clock. The mechanical clock likewise entered the American Midwest as soon as basic survival was secure. Abe Lincoln's boyhood home in Kentucky certainly had no clock on its mantel. But you can bet that his teenage home in Indiana did.

Frontier farm life began and ended with the sun. No one carried appointment books. The only reason anyone needed a clock was for status. A wealthy city-dweller might own one, but not a farmer. Then Eli Terry came along, and all that changed.

Terry was a clock-maker, born in 1780. In those days, clock-makers made one clock at a time. They made them from either wood or brass. Brass clocks cost more, of course. But wooden clocks did well enough, when they didn't suffer too much change in humidity or temperature. Of course that's exactly what they did suffer in early rural America.

Then Terry invented a scheme of mass production -- one of the earliest such schemes. He set up his new machinery in 1800. Two years later, he loaded 200 wooden clocks on a wagon and set out to sell them at $30 a pop. He soon cut that back to $15. In 1814 he unveiled his Terry 30-hour clock. You had to wind it only once a day. You had six hours of grace, if you forgot.

Terry used itinerant peddlers to sell his clocks. Those snake-oil salesmen added Terry clocks to their carts of pots, cloth, and remedies. And they knew their way in the outback. "Keep the clock for nothing. I'll pick it up when I come back next month," one would say. If the wooden gears were malfunctioning by then, no matter. The family was now in love with the clock. It was, after all, the only thing of beauty in a hard world. The salesman would exchange clocks, collect his $15, fix up the used one, and head down the road to the next farmhouse.

Peddlers were soon served by steamboats that filled the vast American West with goods. But those funny, ill-running, unneeded, wooden-geared clocks brought the first measure of beauty and elegance into the lives of bare-subsistence farmers. They were pale reflections of real clocks, but they spoke civilization to people who were there because they meant to make civilization. Clocks spelled order and pattern and the good life. And that's what followed -- order, pattern, and the good life -- right on their heels.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Hawke, D.F., Nuts and Bolts of the Past. New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, 1988, Chapter 9.

For more on Eli Terry, see Episode 1368.

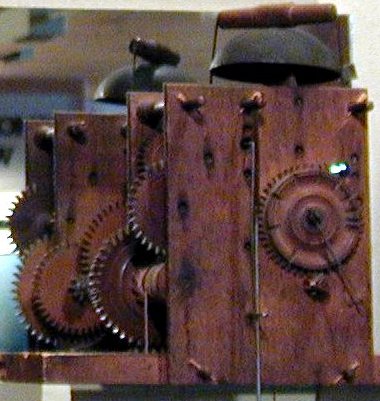

An Eli Terry Clock

Wooden clockwork made by a Terry contemporary