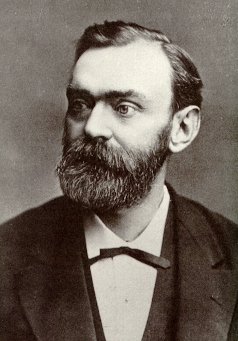

Alfred Nobel

Today, Nobel makes both dynamite and peace. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Alfred Nobel is a kind of dark knight we find riding behind modern science. We know he became rich by inventing dynamite and blasting gelatin. We know he gave his wealth to fund Nobel Prizes for science and for peace. But what do we know beyond that?

Alfred Nobel is a kind of dark knight we find riding behind modern science. We know he became rich by inventing dynamite and blasting gelatin. We know he gave his wealth to fund Nobel Prizes for science and for peace. But what do we know beyond that?

Nobel was born in Stockholm in 1833, the same year his father went bankrupt. The family bounced about from country to country while his father tried one business after another.

By 1861 his father was producing the newest explosive -- nitroglycerin. Nitro is nasty. It's terribly unstable. American railroads were using it to blast out track beds. Europeans were tunneling the Alps with it. It killed off workmen with tedious regularity. Nobel lost one brother to a plant accident.

So he set about to create a stable form of nitroglycerin. In the late 1860s he found he could soak nitro into a porous packing material. The result was dynamite. Dynamite stays stable until you trigger it with a blasting cap. In 1875 Nobel went a step further and created a jelly-like suspension of nitrocellulose and nitroglycerin -- the so-called blasting jelly.

His inventions came on the eve of the great construction projects that followed Western colonial expansion. As we blasted railroads, tunnels, and canals across America, India, and Panama, Nobel grew wealthy.

But not happy! He'd had a messy childhood. He was strongly attached to his mother, and he was subject to depression. He never married. His sexual preference remains a subject of debate. Still, he had several intense, if distant, relations with women.

One was his friendship with the Countess Berta Kinsky von Suttner. She married someone else but continued a lifelong correspondence with Nobel. She worked in the cause of international peace. She certainly influenced Nobel to set up the Peace Prize. She herself won that prize a decade after he died in 1896.

The year before his death, Nobel created the foundation that would give the various prizes. He was adamant that the prizes would be free from any national bias.

A few years before, Berta Kinsky asked Nobel to join her at an international peace conference. No, he said, his explosives advanced the cause of peace faster than her congresses. The day two armies can destroy each other in one second, all civilized nations will recoil from war in horror and disband their armies.

Well, dynamite didn't do that, nor did the H-bomb. Of course, he was whistling in the dark. But, in the end, he did what he could to stem the damage others had done with the fruit of his inventive mind.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Roberts, R.M., Serendipity: Accidental Discoveries in Science. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1989, Chapter 15.

Battered old photo of the author with a "powder monkey." Dynamite serving the greater good in the construction of a forest access road north of Loomis, Washington, in 1949