End of a Card File

Today, I struggle with change. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

I'm standing behind the University of Houston's Library. Tons of file cards, stuffed in cardboard boxes, wait to be hauled off and recycled. I take one for a souvenir. On June 18, 1990, the library trashed its file system. I'm surrounded by two million cards. The staff spent one full lifetime creating them.

Back in the building, they show me a microcomputer. Deep in its stomach are three CD-ROM discs. They look just like your compact disc recording of the Shostakovich 5th Symphony. The holdings of seven regional libraries live on those three discs -- some eight million items. They hold 1800 Mbytes of information.

The old card file cases once filled a thousand square feet of floor space. Now they're part of the state surplus equipment inventory. I've welcomed much of the change that modern technology has given me. But this is hard to digest. After all, what's a library without great ranks of musty drawers leading us to all the things we'd ever care to ask about?

Today, asking is far easier than it's ever been. I saw a book on cultural change during the American Revolution. But I forget its title. So I enter the command, American Revolution plus Cultural. The computer gives me three titles that combine those words. One is the book I couldn't remember. It's A Cultural History of the American Revolution by Silverman.

I've just done what's called a Boolean search. It uses notions from Boolean set theory to search for associated words, anywhere on the disc. I wouldn't get anywhere in a card file with such skimpy recall of a title. Another advantage is that you can't misfile cards on a CD-ROM disc. If the information is there, the machine will find it.

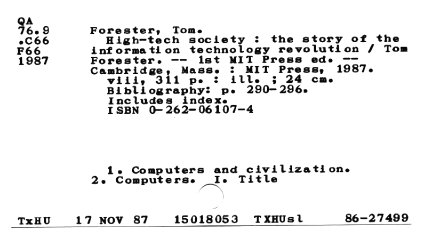

We committed ourselves to this change in 1987. That's when we stopped adding new cards to the file. For three years students had to search both an older computer and the card file to catch everything. These changes are going on in libraries everywhere, but we got into the game earlier than most.

For two centuries now, each generation has had to absorb huge technological changes. As we grow old, we start resisting them. My father flew 14 years after the Wright Brothers did, but he never accepted the pocket calculator. My mother was on the radio while her listeners still used crystal sets, but she never used a dishwasher. She said she liked the feel of hot water on her arthritis. Actually, she was simply tired of change. I'll use this fine new library catalog, but I also feel the gathering loss of a way of life. Sooner or later, I'll dig my in my heels too. But not yet. I'm having too much fun to quit just yet.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

I am grateful to Kathleen Gunning, Assistant Director for Public Services at the the UH Library and the librarian who pointed all this out to me.

The public card catalog perished in 1990 when I wrote this episode.

But as late as 1998 the library still retained another set of cards, ordered by call number, for in-house use. It is called a shelf list.