Cathedral and Pyramid

Today, we look at a cathedral and a pyramid. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

In 450 BC the historian Herodotus wrote about the Great Pyramid. He'd visited Egypt, and he'd brought back stories. The Pyramid was, he told us, built by a hundred thousand slaves. They'd been beaten to death as they labored under the whip.

That picture still lingers, but it was 2000 years off the mark even then. It fit the domination mentality of the Classical World, just as it fits our own darker views of humankind. But it's not how ancient Egypt worked. Slaves didn't build the Great Pyramid. Skilled professional craftsmen did.

Historian H.G. Wells tells us that societies take two forms: "communities of the will" and "communities of obedience." Ancient Israel and the Vikings were communities of the will -- dominating and aggressive. Their leaders were masculine, and so were their gods. But female attributes are woven into both the worship and the thinking of a community of obedience. By obedience, Wells means submission -- not to authority, but to principle. He offers Ancient Egypt and Medieval Europe as examples.

The Virgin Mary gave God a female face in the medieval Church. She took up lodging in the medieval mind and gave masons a new perspective. By submitting themselves to a God who worked through human hands, they cound work miracles. And they did. Listen to a 12th-century witness tell about Chartres Cathedral, and you'll see what Wells meant by a community of obedience:

... when the towers seemed to be rising as if by magic, the faithful harnessed themselves to the carts ... and dragged them from the quarry to the cathedral. The enthusiasm spread throughout France. Men and women came from far away carrying ... provisions for the workmen -- wine, oil, corn. Among them were lords and ladies, pulling carts with the rest. There was perfect discipline and a most profound silence. All hearts were united and each man forgave his enemies.

The magic of that moment grows when we realize that Chartres Cathedral is one of the great architectural miracles of all time.

But so was the Great Pyramid. Its builders worked in gangs of 20 or so. On a busy day you might find 200 gangs on the site. The men proudly signed the stones they hauled. One is marked "The Vigorous Gang," another "The Enduring Gang." One crew, obviously having fun, chiseled, "How drunk the King is!" on their stone. A foreman wrote that his gang toiled

without a single man getting exhausted, without a man thirsting, [and at last they] came home in good spirits, sated with bread, drunk with beer, as if it were the beautiful festival of a god.

Our finest works reflect commitment and ideals. Those monuments were hurled into the sky by workers with a profound belief in their work. And if they were drunk, it wasn't on beer or wine. It was on the elixir of the cause to which they had submitted themselves and the eerie power it'd given to them.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Clark, K., Civilisation. New York: Harper & Row, 1969. (Clark makes several references to Wells's idea and puts it into an artistic and architectural perspective.)

Casson, L., Ancient Egypt. New York: Time Incorporated, 1965.

Photo by John Lienhard

Chartres Cathedral

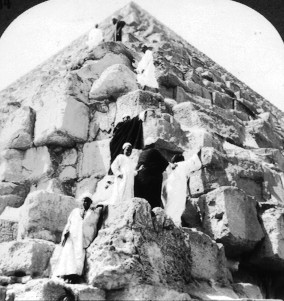

Stereopticon image courtesy of Margaret Culbertson

A view of the Great Pyramid in modern times