Baron Grimthorpe

Today, clocks for the rich and clocks for the poor. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

The American system of manufacturing with interchangeable parts was embryonic in the early 19th century when a man named Eli Terry began using it to make crude wooden clocks. Now I find a book published in 1903. It is Clocks, Watches, and Bells by a man named Grimthorpe, president of the British Horological Institute. This Grimthorpe knows he's somebody. He exudes confidence in his and England's clockmaking superiority. When I look him up, I find he was born in England the year after Napoleon's defeat at Waterloo, and he died not long before WW-I.

At first, Grimthorpe took up law. He made his name as a mean bulldog of a lawyer. Then he began writing tracts on ecclesiastical politics -- issues like the acceptability of marrying your dead wife's sister. He tore into every form of high church, and he strongly opposed revisions of the King James Bible. He built such notoriety on all that combat that he was made a baron. But out of his noisy life emerged a focus: his interest in church architecture and bell towers evolved into genuine expertise in clockwork.

Grimthorpe wrote the first edition of his book on clockwork in 1850. So my edition is a distillation of over fifty years' work on clocks. He designed scores of major bell-tower clocks -- Westminster, St. Paul's. Even the Big Ben clock was his design. Yet he did it all to a backdrop of contention and lawsuits.

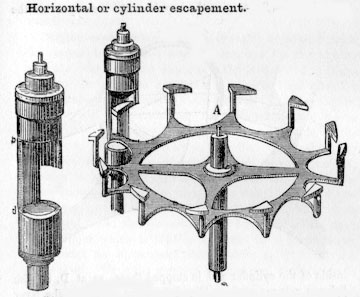

His book describes gear trains, the mathematics of pendulums, ringing systems. He describes every conceivable escapement mechanism. Of American clocks he says that they vary greatly in quality, that some of them use his own escapement design, and that we make our pendulums too lightweight. But the fun begins when he talks about Eli Terry, who created the low-end American clock market by hawking cheap wooden clocks to homesteaders. Grimthorpe calls Terry the Sam Slick of clockmaking.

Sam Slick was an enormously popular fictional character created in Canada in 1838 by another wealthy conservative lawyer. Slick was a garrulous Connecticut clock-maker who peddled cheap clocks in Canada. The Sam Slick stories warned Canadians against upsetting their trade balance with tacky U.S. imports.

Today, the conservative voice of Grimthorpe has been forgotten, while the real Eli Terry and the fictional Sam Slick live on. If we don't remember Sam Slick himself, we do remember his sayings. It was Slick who first said: "The early bird gets the worm" and (with a coy nod to Terry) "Don't take any wooden nickels."

But it was Terry who did with clocks what Henry Ford later did with automobiles. He moved a technology from homes of the wealthy into common life. Terry's clocks never came within a country mile of Grimthorpe's Parliament buildings. But they did bring a first breath of grace and civilization into the cabins of our early West.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Lord Grimthorpe's given name, before he received his title, was Edmund Beckett. He published many books. The one I refer to was

Beckett, E., Lord Grimthorpe, A Rudimentary Treatise on Clocks, Watches, & Bells for Public Purposes. London: Crosby Lockwood and Son, 1903.

Sam Slick was created by Thomas Chandler Haliburton, a judge and resident of Windsor, Nova Scotia, in the early 19th century. The first of these was

Haliburton, T. C., The Clockmaker; or the Sayings and Doings of Samuel Slick, of Slickville. Philadelphia: Carey Lea and Blanchard, 1838. (This book has been reprinted as: Haliburton, T. C., The Clockmaker. Upper Saddle River, N.J., 1969.)

I am grateful to Nancy Day, Linda Hall Library, Kansas City, for providing the Grimthorpe source.

Once of Grimthorpe's illustrations of an escapement mechanism

From Clocks, Watches, and Bells, 1903