Frank Rosenblatt's Perceptron

Today, the origin of learning in artificial neural networks. The University of Houston presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

______________________

The first artificial neural networks couldn't learn. They were composed of units that act like abstract neurons, the cells that make up much of our brains. Yet the connections between these artificial units were fixed. However, our brains aren't static - they change as we experience the world.

Enter Frank Rosenblatt, a psychologist who started from the observation that in brains connections between neurons strengthen and weaken based on experience. Some neurons gain more influence over their neighbors. Others lose their voice. Rosenblatt used this insight to design an artificial neural circuit he called the perceptron.

The perceptron is elegantly simple – a layer of input neurons connect to an output neuron. The input neurons are either on or off. Their state then determines whether the output neuron is on or off. But the impacts of different input neurons are not the same. Some have a strong impact on the state of the output, and the impact of some is weak. Some input neurons push the output neuron to be active, and some push it in the opposite direction. The effect of input neurons is determined by weights, and these weights can change. And those changes in weights allow the network to learn, and, ultimately, to recognize patterns. The perceptron is the ancestor of all neural networks we use today, including the ones under the hood of large language models.

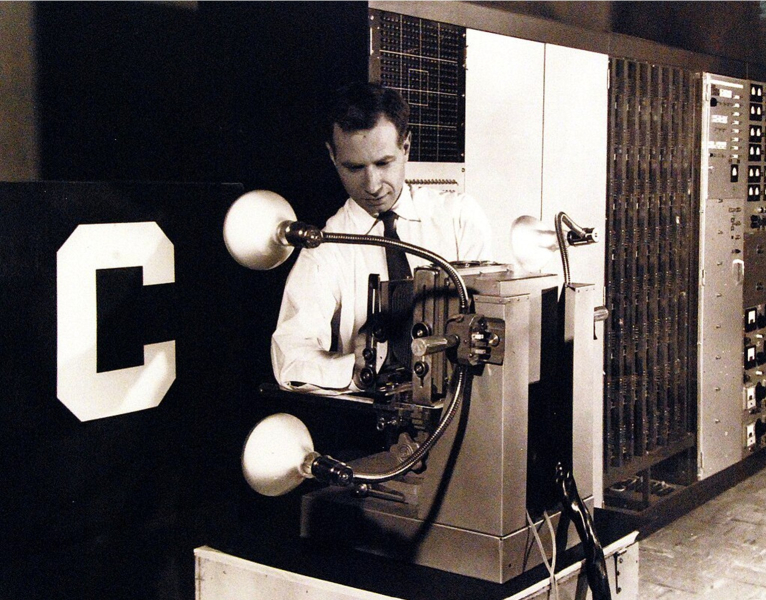

Mark 1 Perceptron, being adjusted by Charles Wightman (Mark I Perceptron project engineer)

Rosenblatt was a showman who loved public demonstrations. He'd train his perceptron to recognize letters while audiences watched. When a journalist asked if his perceptron could read handwriting, Rosenblatt quipped: "Not yet - but it's already better at reading my handwriting than I am!"

The enthusiasm was infectious but short-lived. In the late 1960s, Marvin Minsky and Seymour Papert published a devastating analysis. They proved that Rosenblatt's simple perceptron couldn't solve the exclusive OR problem - outputting FALSE when two inputs are different, and TRUE when they're the same. Thus the perceptron could not determine when two things are the same and when they are different, a problem an infant can solve.

Soon after funding dried up and AI research entered an "AI winter" - a time when money was scarce, and the subject unpopular. Some joked that AI stood for "Always Impossible."

Yet Rosenblatt had planted a seed. His perceptron showed that machines could learn from experience, adapting their behavior as we feed them data. The simple perceptron couldn't solve every problem, but what if you stacked multiple layers of neurons? What if you made the network deeper? These questions simmered for decades before bearing fruit.

And that fruit are today’s trillion-parameter AI models which are descendants of Rosenblatt's perceptron - proof that sometimes a flawed but fertile idea is worth more than a perfect dead end.

This is Krešo Josić at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

A couple articles that provide more information about Frank Rosenblatt and the perceptron can be found here and here.

I also recommend the book “Why Machines Learn” by Anil Ananthaswamy which provides some mathematical details.

This episode first aired November 18, 2025.