Bernardo Zamagna

Today, let us fly with Bernardo Zamagna. The University of Houston presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

______________________

Here’s an epic Latin poem written by a Catholic priest, Bernardo Zamagna, back in 1768. He tells how to build a flying machine. Zamagna wrote it fourteen years before the Montgolfier brothers began building hot air balloons. And Smith College professor, Mary McElwain, translated it in 1939.

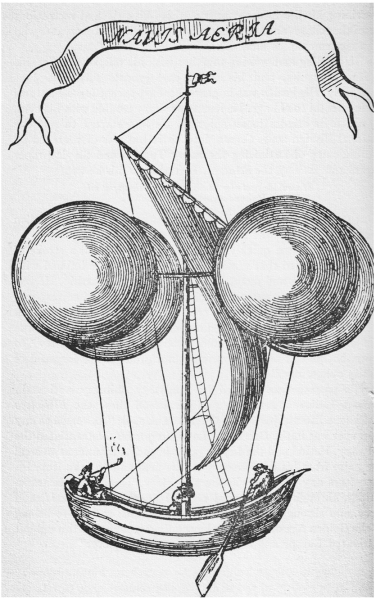

McElwain did so as part of her interest in classic literature. We could hardly expect her to focus on mechanics. Still, she does provide some useful commentary on the machine’s workings. (This, after all, was part of Smith College’s series in Classic Studies.) And the one illustration in Zamagna’s book does give us a pretty clear idea of what he had in mind.

Bernardo Zamagna’s flying machine

Like the Montgolfiers, he imagines lift being provided by lighter-than-air spheres. But, instead of air, his spheres were filled with ... nothing at all ... with a vacuum. Primitive vacuum pumps existed. So, he hoped to evacuate four large spheres.

Then they'd be much lighter than if they'd been filled with hot air. But the air around us exerts huge pressure -- like a large person, standing on the area of a postcard. Any sphere strong enough to withstand that, would’ve weighed far more than it could’ve lifted.

But Zamagna made an even worse error. He expected his airship to navigate the way a ship does. But a balloon moves with the wind, not through it. Inside that moving air, there’s no motion at all. Balloon passengers speak of the eerie quiet – the earth slips away below them, while they seem at rest in a quiet sky.

Zamagna’s picture of his boat-like machine shows one rider smoking a pipe. The smoke drifts backward, even as the wind billows the sail forward, while another rider steers the ship. Ah, but the poetry of it all. McElwain translates: ”The sails drink in the breezes, and the vessel cleaves the fields of air.” One wonders how on earth both inventor and translator failed to see that any such ship would always ride the wind in still air.

Montgolfier’s hot air balloons were likewise quiet captives of the wind. It was finally the dirigible builders of the next century who made sturdy cigar-shaped balloons. And they carried engines to drive propellers.

What value is there, then, in this strange old poem? Well, he did get it right that our entry into the sky would be lighter-than-air. But hot air bags would carry us. And, while the dream got buried in its Latin libraries, something akin to it soon would be realized. You might say that this lost idea was stumbling its way toward inventive reality.

Bernardo Zamagna (image courtesy of Wikimedia)

I’m John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we’re interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Navis Aeria of B. Zamagna, Translated by Mary B. McElwain, The Collegiate Press, George Banta Publishing Co. 1939

This episode first aired on November 17, 2025.