Wayfinding without Instruments

Today, finding our way. The University of Houston presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Imagine we want to take a trip from Point A to Point B. How do we find our way? Most of us would probably use a navigation tool like Google Maps or Waze. Our devices tell us exactly how to get from A to B.

But what if we want to leave Point A for a Point B we don't yet exactly know? To do that, we have to orient ourselves in place and be willing to step into the unkown. We must be wayfinders. Our adventurous human ancestors used wayfinding skills to move across land and sea, populating all parts of the globe. And they did so with only simple tools or none at all, using just their own ingenuity.

Early inhabitants of what we now call Oceania may have been the most extraordinary wayfinders. The Pacific Ocean was their open road. It's a vast expanse of water, studded with far-flung islands. Many of these are tiny, and often hundreds of miles apart.

Yet millennia ago, people navigated across open, uncharted ocean in small but sturdy canoes. They would arrive at one island, settle, and then move on to find another. From islands near Asia - Papua New Guinea and others - they pushed eastward to places like Tuvalu, Tonga, and Tahiti. Polynesians eventually made it to far distant islands like Hawai'i and Rapa Nui (also known as Easter Island). These are far closer to the Americas than to Asia.

How did they find their way? They had no mechanical instruments, no magnetic compass or sextant. Chinese and European mariners invented these much later.

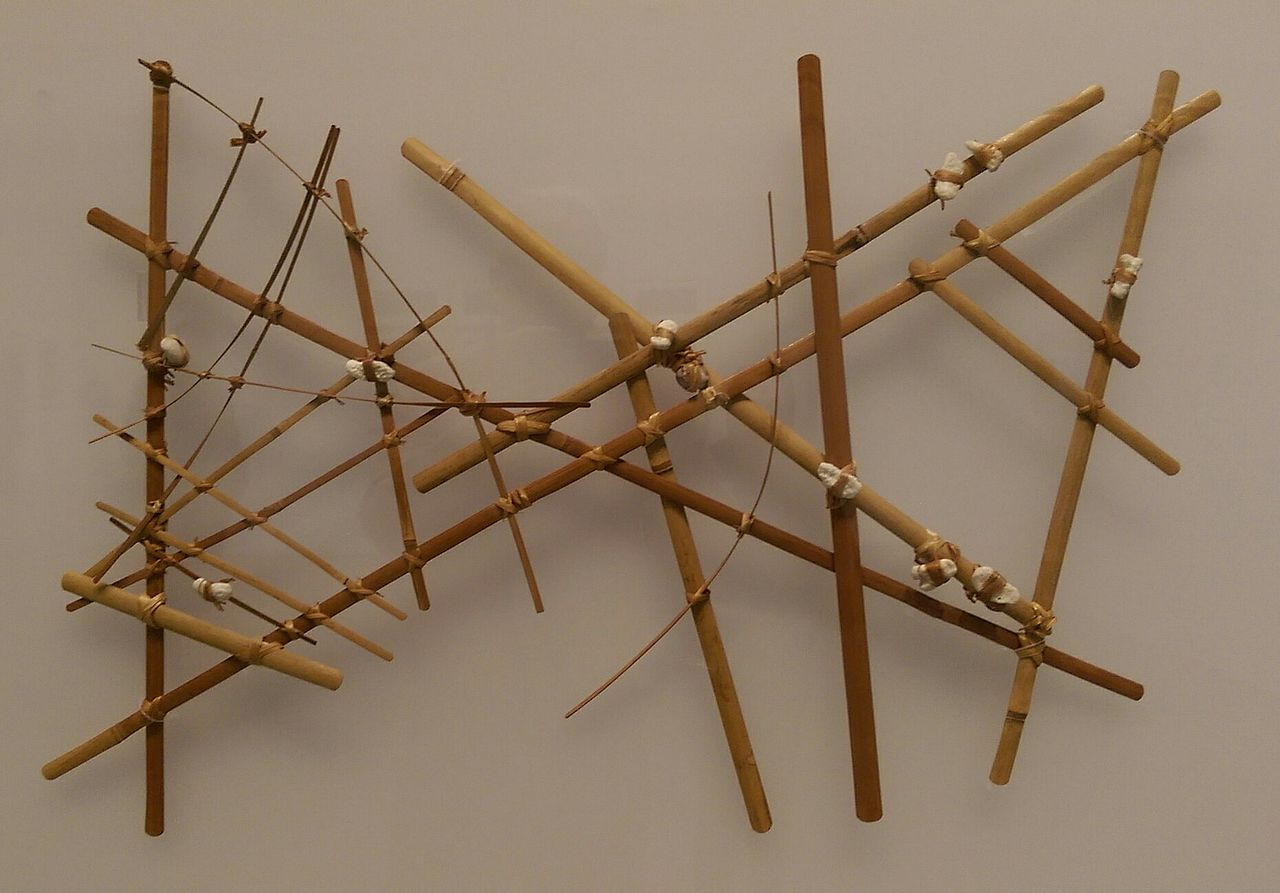

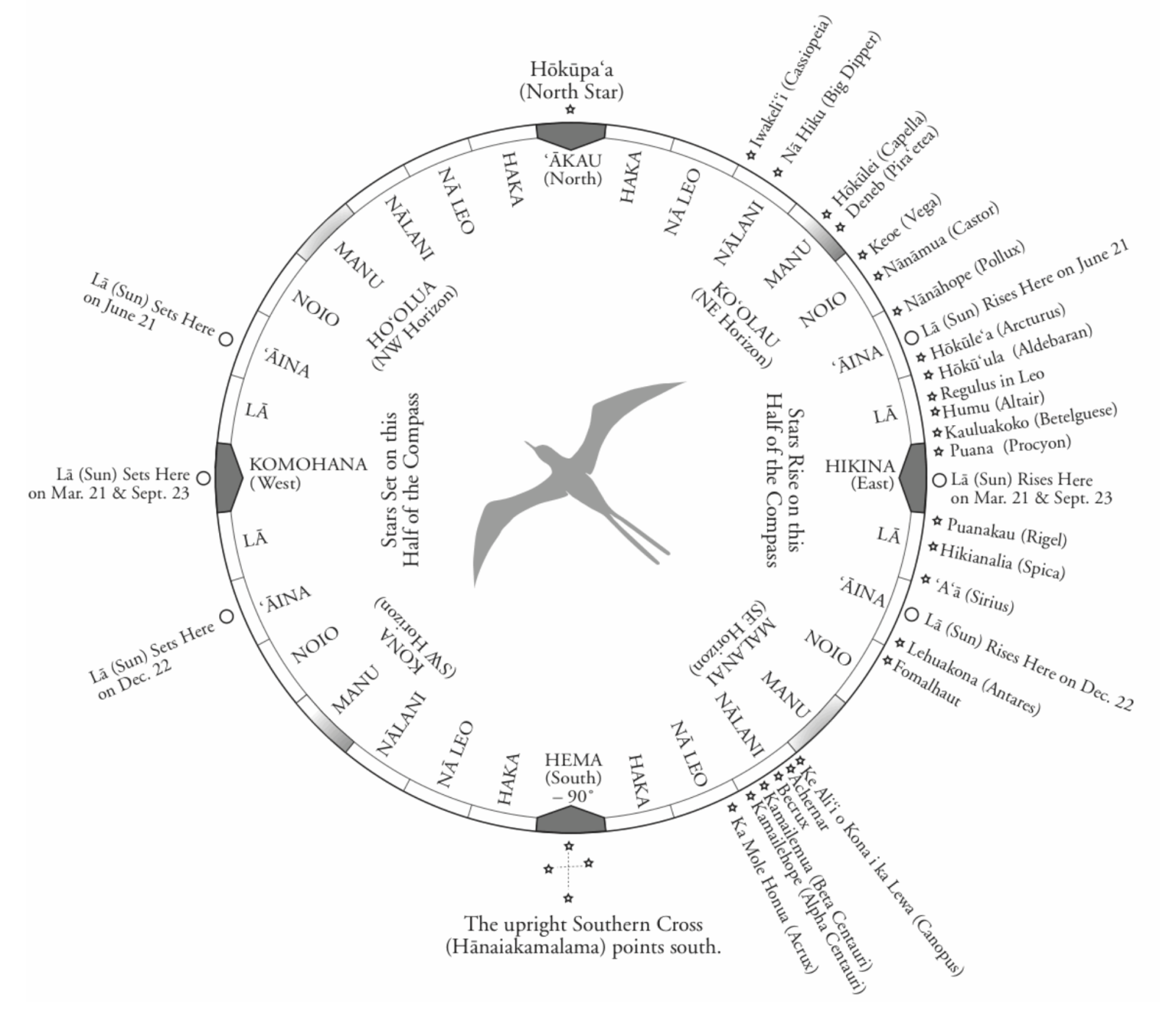

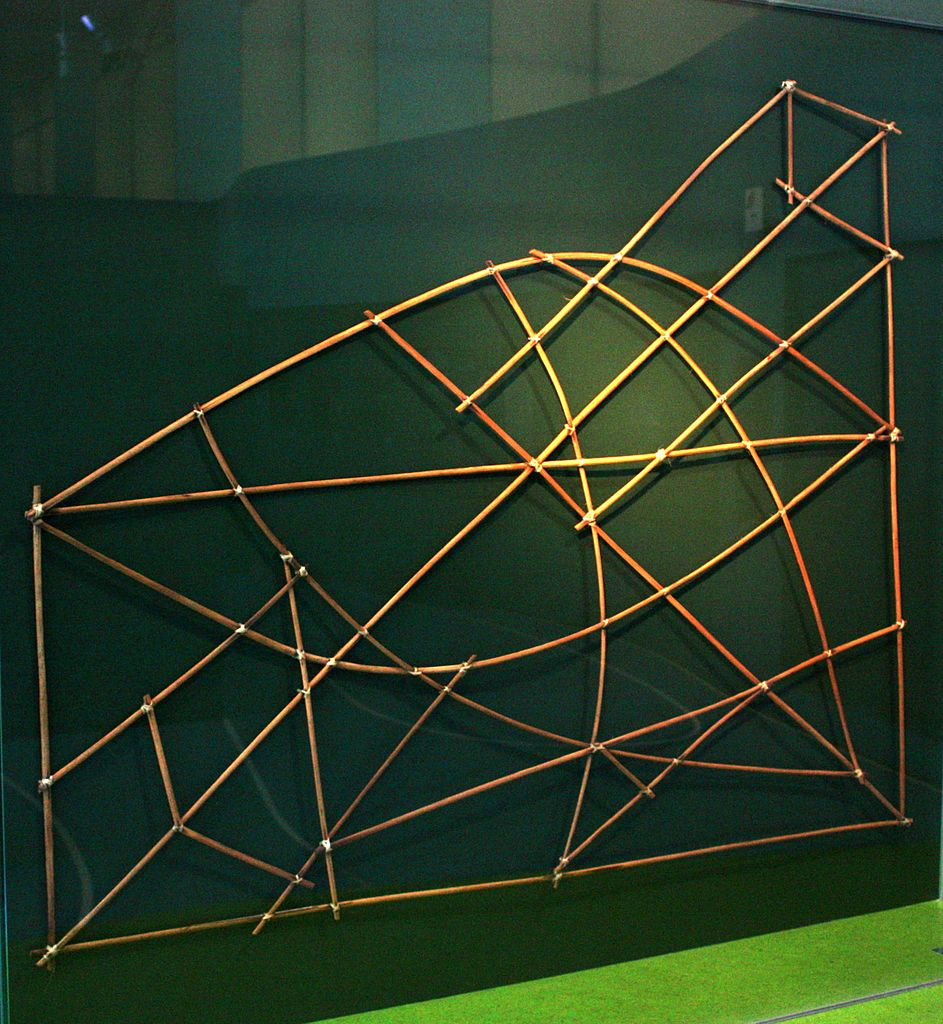

What they did have was a deep awareness of the world around them. They read currents and waves, winds and bird movements like we would read a map. Ocean swells moving in a certain way might signal an island ahead. Stick charts, made out of palm-leaf ribs, coconut fibers, and cowrie shells, helped them visualize the islands and currents they encountered. Master navigators would memorize all the stars in the night sky, where they rose and set. This mental "star compass", along with constant observations of speed, direction, and time, guided wayfinders to distant islands.

Micronesian stick chart

Photo Credit: Wikimedia.

Hawaiian "star compass"

Photo Credit: https://archive.hokulea.com/. This is not a magnetic compass, but rather a graphic representation of the main stars a navigator would memorize in order to calculate directions while traveling on the ocean.

Centuries after the Polynesians settled the islands, Europeans began to sail the Pacific, and they marveled at the navigation skills of the people they met. Without maps or instruments, guided only by their knowledge of sea and skies, Polynesians could set an accurate course across open ocean. Some Pacific Islanders can still do this today.

In our modern world, finding our way is made easier, faster, and safer by our GPS, phones, and apps. But maybe, now and then, we might think of those master wayfinders of the Pacific and set out with just the world around us as guide.

I'm Cathy Patterson at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

Stick chart

Photo Credit: Wikimedia.

(Theme music)

Cathy Patterson is Associate Professor of History at the University of Houston. She is author most recently of Urban Government and the Early Stuart State: Provincial Towns, Corporate Liberties, and Royal Authority, 1603-1640 (The Boydell Press, 2022)

The University of Hawaii at Manoa's Exploring Our Fluid Earth website has an excellent section on "Wayfinding and Navigation" that includes traditional Polynesian/Oceanic methods as well as western ones.

Hawaiian Voyaging Traditions website.

Nicholas Thomas, Voyagers: The Settlement of the Pacific (New York: Basic Books, 2021)

Patrick Kirch, On the Road of the Winds: An Archaeological History of the Pacific Before European Contact (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2000)

On the sextant, see Episode 2899; on the boats that carried Polynesian mariners across the Pacific, see Episode 2722.

This episode was first aired on October 11, 2022