Bias in Face Recognition Software

by Karen Fang

Today, bodies, in beautiful black and white. The University of Houston presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Face recognition software is an exciting field of digital innovation, but it has a problem with race. While the technology grows more pervasive in our daily lives, data shows that some versions are plagued by bias. Women, people of color, or others who do not conform to traditional conventions of power and privilege are often misidentified. This high rate of error can be terribly unfair. It can deny access to rights, such as when a digital passkey fails to recognize an owner or resident because the software isn't good at distinguishing between non-white faces. It can incriminate people for things they did not commit, such as when a platform confuses one person for another, or identifies a suspect based only limited attributes, such as clothing, skin color or headdress.

Face recognition at work. Courtesy of AV-1 and Creative Commons.

Photography is an important predecessor to face recognition technology, and it too has the power to both empower and incriminate. Photos of theater stars and nobility were our first celebrity pin-ups, but mugshots began almost as soon as photography was invented. Photography too has problems registering physical differences. Because photography depends on the calibration of light, dark surfaces can pose a challenge, either in the moment of photographic capture or in the subsequent chemical transfer. For years leading photographic film company, Kodak, received complaints from parents about school pictures in which darker skinned students were never photographed with the same detail and sensitivity as their lighter skinned classmates. Fuji film, a Japanese company, was known to be better at capturing variations in skin tone, and among professional photography and cinematography circles it was common to keep differently hued bodies in separate compositions, under the misguided belief that was the only way to make necessary adjustments in light.

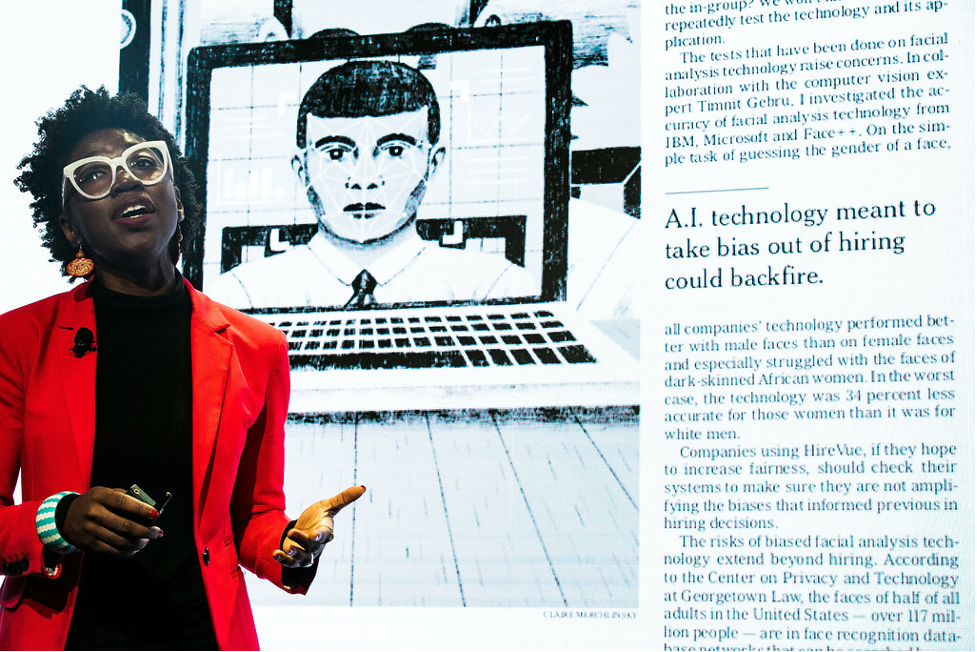

Researcher and activist Joy Buolamwini speaking about data bias at the World Economic Forum in 2019. Image courtesy of Creative Commons and the World Economic Forum..

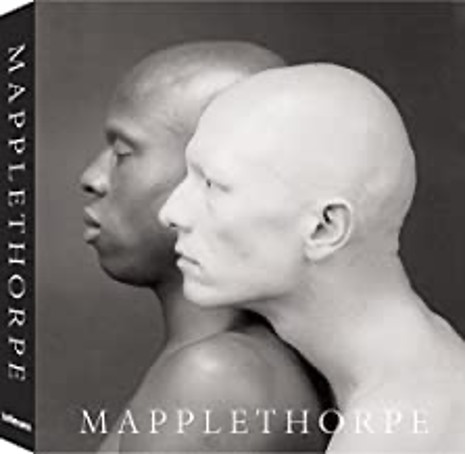

But in both photography and face recognition software, the problem is that these media give the illusion of objectivity, when actually there is little objective about the processes. Instead, this has always been more about skill and priorities than technical limitation. For example, acclaimed portrait photographer Robert Mapplethorpe loved to depict African Americans, precisely because he could "extract a greater richness from their skin." He knew that cameras and other technologies could see darker hues just fine, when provided the conditions to best reflect those surfaces.

Mapplethorpe also did give up on inclusivity, refusing to practice the "separate but equal" tendency of isolating white and black bodies. Instead, by bouncing light around subjects and emphasizing shine as well as glow, Mapplethorpe engineered breathtaking portrait compositions that include white and black bodies in the same frame.

Cover of Robert Mapplethorpe's Mapplethorpe (teNeuues, 2007), one the most widely referenced books on his work.

Today digital technology makes such light adjustments for variations in skin tone easy, and the more accurate face recognition applications have improved their error rate by intentionally prioritizing a more diverse range of data. The lesson here is that technologies and media that promise scientific objectivity actually are most effective when they are programmed and deployed with empathy. If we want to record faces, we have to actually see them.

I'm Karen Fang, for the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

Kashmir Hill, "Wrongfully Accused by an Algorithm." New York Times, June 24, 2020

Coded Bias (film, dir. Shalini Kantayya, 7th Empire Media, 2020)

Guy Hepner Gallery, "Robert Mapplethorpe: Light and Dark."

Nadia Latif, "It's Lit! How Film Finally Learned How to Light Black Skin." Guardian, September 21, 2017

Sarah Lewis, "The Racial Bias Built into Photography" New York Times, April 25, 2019

This episode was first aired on December 1, 2020