The Water Illusion Machine

by Karen Fang

Today, water effects. The University of Houston presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

What do you think is the hardest movie special effect? Is it flying machines and sci-fi spacecraft, like Star Wars? Or is it gargantuan creatures and imaginary monsters, like the beasts and dinosaurs of Godzilla, King Kong and Jurassic Park?

Early film pioneers already were good at these illusions. Decades before digital, the 1924 Douglas Fairbanks' fantasy The Thief of Bagdad already has both those effects. A scorpion, shot in close-up and composited with flames, looks like a fire-breathing dragon. Fabric pulled on wire against the backdrop of miniature buildings makes a flying carpet.

So it might surprise you that one of cinema's most challenging special effects is water, a natural element that is very hard to fake. Insects and model miniatures can always be shot with scaled props and backgrounds to give the illusion of being smaller or larger, but water defies trick photography. While you can build a model ship that looks realistic, ripples and waves are dictated by natural forces. Against the small size of a model ship, even the tiniest ripples look like a tidal wave.

(wave sound)

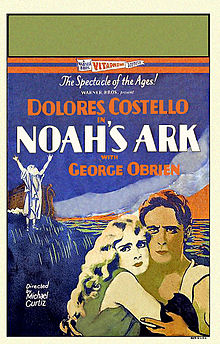

But using real water on film sets can have terrible consequences. In 1928, a film version of Noah's Ark was to climax with a scene of the Biblical Flood. Production plans called for the sudden release of 600,000 gallons of water (the volume of an Olympic swimming pool). The head cameraman was so appalled at the danger that he quit in protest. When the scene was shot, three extras drowned.

Movie poster for 1928 film, Noah's Ark (courtesy of Warner Bros.).

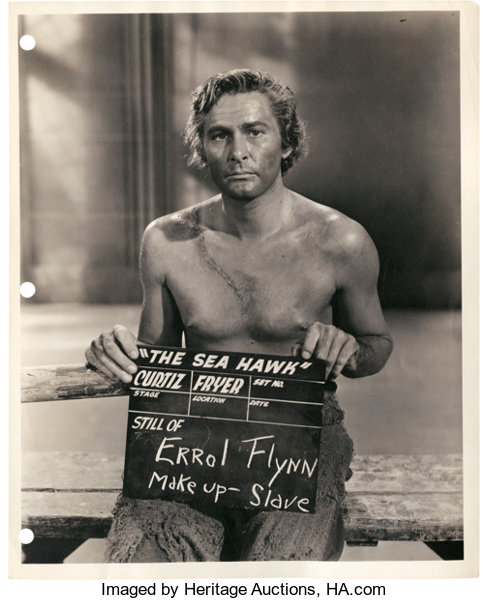

Thankfully, within a dozen years water effects like that in the Noah's Ark movie tragedy had a better solution. For the 1940 Errol Flynn swashbuckler, The Sea Hawk, Noah's Ark director Michael Curtiz was again at the helm of a sea-faring spectacle requiring huge aquatic scenes. Curtiz was a crotchety perfectionist indifferent to safety, but he picked his art directors carefully. On The Sea Hawk, gifted Warner Bros. art directors Anton Grot and Leo Kuter, who probably feared repeating the Noah's Ark's tragedy, invented a contraption that could give the appearance of moving water, without requiring any water at all.

Studio test photo of Errol Flynn on set of The Sea Hawk, 1940 (courtesy of Warner Bros. and Heritage Auctions).

The Water Ripple and Wave Illusion Machine is a backdrop of layered acetate scrims, painted with dark horizontal squiggles and mounted on rollers. When light shines through the layered acetate, and the scrims move on the rollers, the effect resembles the sparkle of sunlight on water. Combined with a painted background and Warner Bros.' vast indoor pool, the Water Illusion machine can give the look of endless ocean. When backlit behind actors or miniature ships, its shimmering lights simulate water's movement, even on a completely dry set.

As a film The Sea Hawk is sometimes remembered as a World War II allegory, a nautical yarn about brave adventurers battling invaders meant to drum up support for the Allied cause. The Sea Hawk, in this sense, was meant to save lives--but it also saved lives more directly by preventing catastrophic tragedies that earlier films like Noah's Ark caused. Hollywood, and war history, has many heroes. One of them is Anton Grot and Leo Kuter's Water Ripple and Wave Illusion Machine.

Kay Kuter, "A Picture-Perfect World." Unpublished manuscript, Kay E. Kuter book proposal, Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Beverly Hills. Courtesy of the Margaret Herrick Library.

I'm Karen Fang, for the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

Steve Bingen, Warner Bros.: Hollywood's Ultimate Back Lot. Taylor Trade, 2014.

Kay Kuter, "A Picture-Perfect World." Unpublished manuscript, Kay E. Kuter book proposal, Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Beverly Hills. Courtesy of the Margaret Herrick Library

This episode was first aired on September 16, 2020